So here is a musical science-fiction fantasy filmed in black-and-white with color sequences, produced by Lorne Michaels, featuring appearances by Bill Murray and Dan Aykroyd the same year they made Ghostbusters, written and directed by Saturday Night Live writer Tom Schilling in a manner which pays homage to Fritz Lang, Sergei Eisenstein, and 1930’s musical comedies. Do I have your attention? Nothing Lasts Forever (1984) has never been released on home video, and although Bill Murray introduced a special screening of the film in Brooklyn in 2004, it’s since drifted back to dormancy. The film deserves better; it’s not a lost masterpiece, but its obscurity is criminal.

So here is a musical science-fiction fantasy filmed in black-and-white with color sequences, produced by Lorne Michaels, featuring appearances by Bill Murray and Dan Aykroyd the same year they made Ghostbusters, written and directed by Saturday Night Live writer Tom Schilling in a manner which pays homage to Fritz Lang, Sergei Eisenstein, and 1930’s musical comedies. Do I have your attention? Nothing Lasts Forever (1984) has never been released on home video, and although Bill Murray introduced a special screening of the film in Brooklyn in 2004, it’s since drifted back to dormancy. The film deserves better; it’s not a lost masterpiece, but its obscurity is criminal.

Tom Schilling’s film is a fairy tale, and obviously a very personal project, but it draws upon its influences, sorts through them, and spits them back out in strangely reconfigured shapes. It’s what you would call a movie-movie; it basks in the glow of cinephelia. A young Zach Galligan (Gremlins) plays the bright-eyed, good-hearted Adam Beckett, who, at the movie’s start, is playing Chopin on piano at Carnegie Hall. He’s humiliated, Milli-Vanilli style, when it proves to be a player piano, exposing him as a fraud. (A bearded prospector in long underwear, holding a rifle in his hands, stands up in the audience and shouts accusingly, “It’s a player pian-ey! He’s a fake! Get ‘im!”) New York’s finely-tailored upper crust storm the stage, gut the piano of its “music rolls,” and wrap Adam up in them like a mummy. He then awakens from his nightmare, covered in sweat, though it should be noted that the rest of this film plays just as dream-like, with no discernable contrast from what’s just transpired. He’s on a train in Europe sitting across from a Swedish architect, and when Adam confesses his self-doubt, and his longings to be a true artist, the architect encourages him to go to New York to pursue his dream. “I want you to know one thing,” he tells Adam. “You will get everything you want in your lifetime, only you won’t get it the way you expect.”

Tom Schilling’s film is a fairy tale, and obviously a very personal project, but it draws upon its influences, sorts through them, and spits them back out in strangely reconfigured shapes. It’s what you would call a movie-movie; it basks in the glow of cinephelia. A young Zach Galligan (Gremlins) plays the bright-eyed, good-hearted Adam Beckett, who, at the movie’s start, is playing Chopin on piano at Carnegie Hall. He’s humiliated, Milli-Vanilli style, when it proves to be a player piano, exposing him as a fraud. (A bearded prospector in long underwear, holding a rifle in his hands, stands up in the audience and shouts accusingly, “It’s a player pian-ey! He’s a fake! Get ‘im!”) New York’s finely-tailored upper crust storm the stage, gut the piano of its “music rolls,” and wrap Adam up in them like a mummy. He then awakens from his nightmare, covered in sweat, though it should be noted that the rest of this film plays just as dream-like, with no discernable contrast from what’s just transpired. He’s on a train in Europe sitting across from a Swedish architect, and when Adam confesses his self-doubt, and his longings to be a true artist, the architect encourages him to go to New York to pursue his dream. “I want you to know one thing,” he tells Adam. “You will get everything you want in your lifetime, only you won’t get it the way you expect.”

He returns to New York City to find it paralyzed by a bus-driver’s strike and an influx of immigrants from Los Angeles, which has been leveled by a massive earthquake. To restore order, the New York Port Authority has taken over the city like a fascist regime. All of this back-story, by the way, is told with found stock footage that meshes fairly seamlessly with the grainy black-and-white that dominates the film. In that manner, it’s reminiscent of Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, the Carl Reiner film from two years earlier which convincingly placed Steve Martin into old film noirs. Similarly, Nothing Lasts Forever has the look of an early-30’s studio picture. Sets occasionally call to mind Metropolis (1927) and Things to Come (1936), although the New York Schilling presents is set neither in the distant past nor in the far future (an apt comparison would be Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, dystopian but cluttered with relics of the past). Adam applies with the Port Authority to be an artist, which sends him to an office building where he’s asked to fill out some forms and submit to an “artist’s test”: he’s thrust into a small chamber where a woman doffs her clothes, and he must complete a life drawing within about thirty seconds. His work is deemed unsuitable, so he’s transferred to the Holland Tunnel, where he monitors traffic under the supervision of a no-nonsense Dan Aykroyd.

He returns to New York City to find it paralyzed by a bus-driver’s strike and an influx of immigrants from Los Angeles, which has been leveled by a massive earthquake. To restore order, the New York Port Authority has taken over the city like a fascist regime. All of this back-story, by the way, is told with found stock footage that meshes fairly seamlessly with the grainy black-and-white that dominates the film. In that manner, it’s reminiscent of Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, the Carl Reiner film from two years earlier which convincingly placed Steve Martin into old film noirs. Similarly, Nothing Lasts Forever has the look of an early-30’s studio picture. Sets occasionally call to mind Metropolis (1927) and Things to Come (1936), although the New York Schilling presents is set neither in the distant past nor in the far future (an apt comparison would be Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, dystopian but cluttered with relics of the past). Adam applies with the Port Authority to be an artist, which sends him to an office building where he’s asked to fill out some forms and submit to an “artist’s test”: he’s thrust into a small chamber where a woman doffs her clothes, and he must complete a life drawing within about thirty seconds. His work is deemed unsuitable, so he’s transferred to the Holland Tunnel, where he monitors traffic under the supervision of a no-nonsense Dan Aykroyd.

One of his co-workers is a German girl named Mara (Apollonia van Ravenstein), and when he follows her to the joint where she spends her free time (think: Andy Warhol’s Factory recycled through an early Duran Duran video), he discovers that being a hardcore artist in New York means taking yourself very, very seriously. Television monitors show the eye-slitting scene from Un Chien Andalou. A shirtless German man marches on a treadmill while counting his steps, and an audience pays rapt attention. Mara gives Adam a book on Dadaism for him to study like homework. They have sex, but she interrupts her orgasm when she sees that Battleship Potemkin is playing on her tiny, tiny television set (it’s much like viewing great cinema on an iPhone; appropriately, Adam complains). But in his spare time, he drifts off to Carnegie Hall to look longingly through its doors, and there meets a bum named Hugo. They discuss Adam’s dreams of being an artist, and he offers food and shelter, which Hugo politely declines. Still, this moment of kindness reaps an unexpected reward. Some time later Hugo visits Adam in the Holland Tunnel and urges him to follow immediately. Hugo, it seems, is part of a secret society of hobos; as they pass through a portal and journey beneath the city, Hugo reveals that all of New York is a dream controlled by a greater intelligence. They organize and manipulate the souls of its citizens, which take the form of ticker tape.

One of his co-workers is a German girl named Mara (Apollonia van Ravenstein), and when he follows her to the joint where she spends her free time (think: Andy Warhol’s Factory recycled through an early Duran Duran video), he discovers that being a hardcore artist in New York means taking yourself very, very seriously. Television monitors show the eye-slitting scene from Un Chien Andalou. A shirtless German man marches on a treadmill while counting his steps, and an audience pays rapt attention. Mara gives Adam a book on Dadaism for him to study like homework. They have sex, but she interrupts her orgasm when she sees that Battleship Potemkin is playing on her tiny, tiny television set (it’s much like viewing great cinema on an iPhone; appropriately, Adam complains). But in his spare time, he drifts off to Carnegie Hall to look longingly through its doors, and there meets a bum named Hugo. They discuss Adam’s dreams of being an artist, and he offers food and shelter, which Hugo politely declines. Still, this moment of kindness reaps an unexpected reward. Some time later Hugo visits Adam in the Holland Tunnel and urges him to follow immediately. Hugo, it seems, is part of a secret society of hobos; as they pass through a portal and journey beneath the city, Hugo reveals that all of New York is a dream controlled by a greater intelligence. They organize and manipulate the souls of its citizens, which take the form of ticker tape.

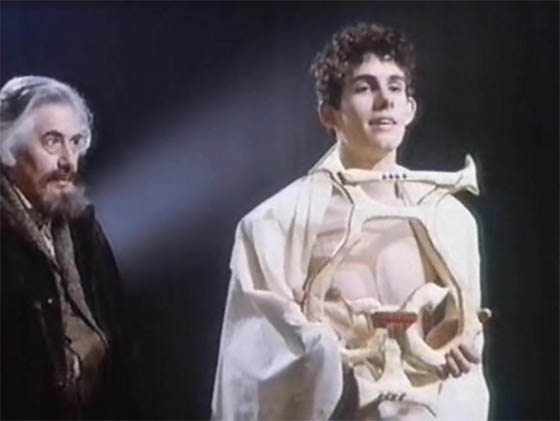

The journey beneath New York also marks a transition from black-and-white to color, Wizard of Oz-like, and the pale hues call to mind color films of the 1940’s. That is, even in color, Nothing Lasts Forever resists the look of 1984. It still looks like a lost artifact recovered from a celluloid vault. In the secret city, Adam is cleaned and washed by old, semi-nude men, and delivered in a toga to a command chamber where he meets Father Knickerbocker (veteran character actor Sam Jaffe, who died the year this was released). He’s told that because he’s pure of heart and dreams of being a true artist, he has been selected to achieve his dreams. He’ll journey to the Moon and meet his true love, named Eloy. The hows and the whys are sketchy.

The journey beneath New York also marks a transition from black-and-white to color, Wizard of Oz-like, and the pale hues call to mind color films of the 1940’s. That is, even in color, Nothing Lasts Forever resists the look of 1984. It still looks like a lost artifact recovered from a celluloid vault. In the secret city, Adam is cleaned and washed by old, semi-nude men, and delivered in a toga to a command chamber where he meets Father Knickerbocker (veteran character actor Sam Jaffe, who died the year this was released). He’s told that because he’s pure of heart and dreams of being a true artist, he has been selected to achieve his dreams. He’ll journey to the Moon and meet his true love, named Eloy. The hows and the whys are sketchy.

He does make it to the Moon, though not through any effort on his part. After running through a rainy, empty street at night, he takes shelter in a bus occupied by senior citizens. It quickly becomes apparent that they’re on a trip which he’s interrupted, much to the consternation of their tour director, played by Bill Murray. It’s no ordinary bus, as he quickly learns: Murray and a flight attendant tell the passengers to extinguish their cigarettes and buckle their seat belts, and instructions are given on operating the oxygen masks overhead, “in case of emergency.” The bus launches its rockets and soars off the road and above New York City, eventually escaping Earth’s atmosphere, in some deliberately retro FX. (Both the Earth and the Moon are supposed to look that two-dimensional.) When he’s free to move about the cabin, Adam quickly learns that, like the TARDIS, the bus is larger on the inside than the outside. There’s a lounge where cocktails are served and Eddie Fisher performs. (“How the hell did I end up singing on a bus to the Moon?” “Must’ve been all those women, Mr. Fisher.”) Adam talks to one Daisy Schackman (Imogene Coca), who explains that the elderly visit the Moon all the time, only chips implanted in the backs of their necks (X-Files style) force them to say the word “Miami” instead of “The Moon.” The government also postmarks all the vacationers’ correspondence from Florida, to keep up the ruse.

He does make it to the Moon, though not through any effort on his part. After running through a rainy, empty street at night, he takes shelter in a bus occupied by senior citizens. It quickly becomes apparent that they’re on a trip which he’s interrupted, much to the consternation of their tour director, played by Bill Murray. It’s no ordinary bus, as he quickly learns: Murray and a flight attendant tell the passengers to extinguish their cigarettes and buckle their seat belts, and instructions are given on operating the oxygen masks overhead, “in case of emergency.” The bus launches its rockets and soars off the road and above New York City, eventually escaping Earth’s atmosphere, in some deliberately retro FX. (Both the Earth and the Moon are supposed to look that two-dimensional.) When he’s free to move about the cabin, Adam quickly learns that, like the TARDIS, the bus is larger on the inside than the outside. There’s a lounge where cocktails are served and Eddie Fisher performs. (“How the hell did I end up singing on a bus to the Moon?” “Must’ve been all those women, Mr. Fisher.”) Adam talks to one Daisy Schackman (Imogene Coca), who explains that the elderly visit the Moon all the time, only chips implanted in the backs of their necks (X-Files style) force them to say the word “Miami” instead of “The Moon.” The government also postmarks all the vacationers’ correspondence from Florida, to keep up the ruse.

You see, a colony has been established on the Moon since the 1950’s, and it now serves as both a shopping mall and a tourist trap. The original lunar inhabitants have been subjugated and forced to work for the colonists. They greet the arrivals with some hula dancing, while Bill Murray translates the meaning of the dance. Foremost among them is the girl for whom Adam is predestined, Eloy, played by Lauren Tom. Yes, the same Lauren Tom who voices Amy Wong on Futurama, which, in its first season, also portrayed the Moon as a giant tourist trap. So go ahead and pretend that Zach Galligan is Fry, and this is a live-action version of Futurama; knock yourself out. The Moon is so cartoonish that it would encourage such an interpretation; it looks like it was inspired by “Marvin the Martian” shorts. It’s an obvious set, with a deliberately flat backdrop. To see the bus pull up on the set, before the waiting hula dancers (who have small antennae upon their heads), and the senior citizens pile out wearing their New Wave-ish “lunar glasses” – including one ecstatic Larry “Bud” Melman – really just makes the whole film worthwhile. I scribbled down a number of movie titles while watching this, and one of them was Forbidden Zone. An Oingo Boingo score would seem appropriate.

You see, a colony has been established on the Moon since the 1950’s, and it now serves as both a shopping mall and a tourist trap. The original lunar inhabitants have been subjugated and forced to work for the colonists. They greet the arrivals with some hula dancing, while Bill Murray translates the meaning of the dance. Foremost among them is the girl for whom Adam is predestined, Eloy, played by Lauren Tom. Yes, the same Lauren Tom who voices Amy Wong on Futurama, which, in its first season, also portrayed the Moon as a giant tourist trap. So go ahead and pretend that Zach Galligan is Fry, and this is a live-action version of Futurama; knock yourself out. The Moon is so cartoonish that it would encourage such an interpretation; it looks like it was inspired by “Marvin the Martian” shorts. It’s an obvious set, with a deliberately flat backdrop. To see the bus pull up on the set, before the waiting hula dancers (who have small antennae upon their heads), and the senior citizens pile out wearing their New Wave-ish “lunar glasses” – including one ecstatic Larry “Bud” Melman – really just makes the whole film worthwhile. I scribbled down a number of movie titles while watching this, and one of them was Forbidden Zone. An Oingo Boingo score would seem appropriate.

Instead, the score is lush and romantic. It’s by Howard Shore, another SNL veteran, who would later become one of our most esteemed film composers thanks to Lord of the Rings. His theme is based upon Chopin, and also the film’s theme song “Nothing Lasts Forever,” which is delivered by Eloy and Adam when they meet and fall in love in her little lunar villa. Lauren Tom is dubbed, and reaches some pretty high notes. (Anita Ellis, who plays Adam’s Aunt Anita, also gets to sing a number in an early party scene.) The stay on the Moon is short, though there are some funny bits involving its rampant commercialization; pretty soon Bill Murray punches Adam in the face, and he wakes up back in New York City. But it’s not a dream, he’s told – and he needs to get to Carnegie Hall for his debut performance.

Instead, the score is lush and romantic. It’s by Howard Shore, another SNL veteran, who would later become one of our most esteemed film composers thanks to Lord of the Rings. His theme is based upon Chopin, and also the film’s theme song “Nothing Lasts Forever,” which is delivered by Eloy and Adam when they meet and fall in love in her little lunar villa. Lauren Tom is dubbed, and reaches some pretty high notes. (Anita Ellis, who plays Adam’s Aunt Anita, also gets to sing a number in an early party scene.) The stay on the Moon is short, though there are some funny bits involving its rampant commercialization; pretty soon Bill Murray punches Adam in the face, and he wakes up back in New York City. But it’s not a dream, he’s told – and he needs to get to Carnegie Hall for his debut performance.

In many ways, Nothing Lasts Forever is a slight film. The stream-of-consciousness plot is inconsequential, and never really generates substantial conflict or momentum. It’s a paper-thin fable that doesn’t quite make it to 80 minutes, and doesn’t have anything of great profundity to impart. In other words, it could have been a short; and given how seldom it’s been screened, it might as well have been. But in many ways the film is a revelation. It prefigures the work of Guy Maddin (the color sequences look like his film Careful, and the storytelling, though lighter on the sexual repression, is of a retro-fabulist nature akin to Maddin’s many works). It’s visually striking continuously, from its German Expressionist interpretation of the Big Apple, to a Moon suited to Georges Méliès. The humor is gentle, for everything is glossed in nostalgia. That so much of the cast is peppered with familiar faces from yesteryear is central to the film’s recurring theme of the old being unduly ignored and pushed aside. In Tom Schilling’s imagination, the old, downtrodden bums are really powerful mystics controlling the Fates; and your grandparents aren’t going to Miami, but to the Moon no less, if only they could tell you. Similarly, he rescues the outdated styles of the films of yesteryear, which are even more remote today. Now if only someone could rescue Nothing Lasts Forever. I would expect that in 2011 it would find a wider and more appreciative audience than it did in 1984.

In many ways, Nothing Lasts Forever is a slight film. The stream-of-consciousness plot is inconsequential, and never really generates substantial conflict or momentum. It’s a paper-thin fable that doesn’t quite make it to 80 minutes, and doesn’t have anything of great profundity to impart. In other words, it could have been a short; and given how seldom it’s been screened, it might as well have been. But in many ways the film is a revelation. It prefigures the work of Guy Maddin (the color sequences look like his film Careful, and the storytelling, though lighter on the sexual repression, is of a retro-fabulist nature akin to Maddin’s many works). It’s visually striking continuously, from its German Expressionist interpretation of the Big Apple, to a Moon suited to Georges Méliès. The humor is gentle, for everything is glossed in nostalgia. That so much of the cast is peppered with familiar faces from yesteryear is central to the film’s recurring theme of the old being unduly ignored and pushed aside. In Tom Schilling’s imagination, the old, downtrodden bums are really powerful mystics controlling the Fates; and your grandparents aren’t going to Miami, but to the Moon no less, if only they could tell you. Similarly, he rescues the outdated styles of the films of yesteryear, which are even more remote today. Now if only someone could rescue Nothing Lasts Forever. I would expect that in 2011 it would find a wider and more appreciative audience than it did in 1984.