As vividly illustrated in the new film Woody Allen: A Documentary (2011), by the late 60’s Woody Allen was such a tremendous celebrity that on national television he was belting out songs in a top hat before the giant letters W-O-O-D-Y, and boxing a real live kangaroo while the audience cheered him on. In What’s New Pussycat? (1965) and Casino Royale (1967), a few of his trademark one-liners survived while the directors did their level best to deplete as much actual comedy as possible from the finished products. Hollywood comedy in this period usually amounted to star-studded casts, slapstick chases, sexual innuendo, and pie fights; of course Woody Allen seemed like the Second Coming. But he needed to wrest control of his own films. Beginning with the pitch-perfect Take the Money and Run (1969), Allen began filming his scripts – at a low budget and with complete independence. At last, his comic voice was captured intact on-screen, though his talents as a director were still somewhat unpolished. The film was a hit, allowing him to make Bananas (1971), a manic vehicle which paid homage to the Marx Brothers and Bob Hope. For his next film, he turned to a far more unusual inspiration: the bestselling sex manual of 1969 by David Reuben, M.D., Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask).

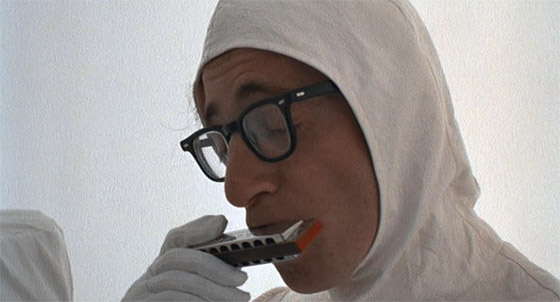

The rabbit-themed opening credits, set to Cole Porter's "Let's Misbehave."

The timing was right for Allen’s comedy to explore sexuality in all its amusing variations. In 1972, the release of Deep Throat had launched “porno chic,” and society’s elite were lining up at theaters to attend X-rated films; it was one of the stranger fads of the twentieth century, as the free love of the hippies had eroded into the more decadent liberation of the 1970’s. In the realm of art house film, pictures like Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972), Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life” (beginning with The Decameron in 1971), and Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971) used sex to explore politics and human nature. Enter Woody Allen, with his comic persona of the bespectacled nebbish, thrust into this world of wild sexual license: horny, intimidated, and always ready with a one-liner delivered, as a self-defense mechanism, directly to the camera. This character drifts through one comic skit after another in the film version of Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex – which is what, by now, his fans demanded – but with the benefit of hindsight we can see how Allen was also starting to develop his talents as a director.

Dr. Ross (Gene Wilder) reacts to the news that his patient has been having unapologetic sexual relations with a sheep named Daisy.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the film’s second segment, “What is Sodomy?” (Allen structures the film by creating his own answers to questions from Reuben’s book.) Gene Wilder plays Dr. Ross, a clinical physician treating an Armenian patient, Milos (Titos Vandis), who one day explains that he’s in love with a sheep named Daisy (“the best lay I ever had”). Milos wants Ross to see Daisy, to find out why she’s been so aloof lately – and while Ross strenuously objects, Milos runs outside, fetches the sheep from a truck, and carries it through the waiting room crowded with patients. “You’ll have to excuse me,” Ross stammers to the gathered throng, “his sheep has a strep throat.” In the natural comic escalation of an Allen short story, Ross unexpectedly falls in love with Daisy, and steals her off to a hotel room, where he orders from room service “chilled white burgundy, a little caviar, and some grass – oh, just plain, green grass.” After a blissful affair, his life begins to fall apart, until a betrayed Milos angrily comes to take Daisy back to Armenia. What makes this segment special is how Allen handles it: now that he’s entirely behind the camera and not playing the clown in front of it, he can experiment with a different tone, spotlighting Wilder’s own acting style, which is played by reacting naturally to comic circumstances rather than using Groucho Marx one-liners. And this dramatic, realistic style of acting is what you need when the premise of the sketch is this outlandish. (It’s a shame that this is the only collaboration we have between these two comic greats, since Wilder is so good at delivering Allen’s dialogue.) But also look at the montage which opens this segment: a breakdown of Dr. Ross’s daily life into brief moments lasting only a few seconds long, cold, reserved, businesslike, all to establish a tone that can be deliberately undermined by the introduction of comic absurdity (Milos and Daisy). If you had come into the theater late, you might think you’d arrived at the wrong film. This was not the same man who had directed Bananas. He was proving he could adapt his style to suit the material, which would serve him invaluably in films to come.

Fabrizio (Woody Allen) can only sexually satisfy his wife Gina (Louise Lasser) by making love in public.

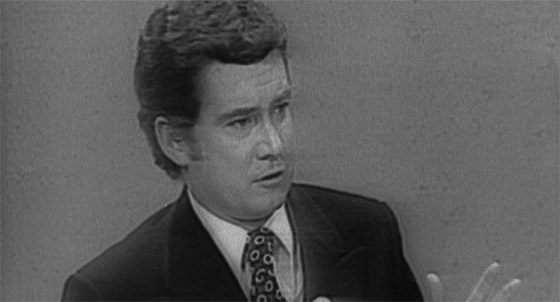

A further stylistic experiment arrives with “Why Do Some Women Have Trouble Reaching an Orgasm?” Allen takes a simple idea – a man discovers his frigid wife can only be sexually excited by making love in public places – and makes it much funnier than it ought to be by treating it as a parody of the kind of 60’s Italian movies that usually starred Marcello Mastroianni. Allen makes a strange substitute in that role, but wears the sunglasses and gold jewelry and carries off the machismo necessary, speaking in phonetically-learned Italian with subtitled lines like “But you just lay there passive, like a lox.” As the camera follows the husband and wife (Allen is Fabrizio, and Gina is played by Allen’s ex-wife Louise Lasser) through restaurants and film studios, the director proves himself capable of creating a mise-en-scéne in the style of Fellini, Visconti, or Antonioni, but funnier. As Fabrizio’s friend closes in on him, questioning his sexual ability against a towering, blank wall (dwarfing Allen), he asks him delicately, “Are you…small?” “Small?” Fabrizio scoffs. “Like a French bread! Small.” To answer the question “What Are Sex Perverts?”, Allen successfully imitates the style of a 1950’s black-and-white game show, replete with spotty reception. Allen’s game show features Jack Barry of “What’s My Line?” hosting “What’s My Perversion?”, in which celebrity guests like Regis Philbin try and fail to guess that a contestant likes to expose himself on the subway. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex also offers Allen the opportunity to parody Hamlet and horror B-movies.

Regis Philbin is a celebrity guest on "What's My Perversion?": "When you're doing your perversion, do you have any need for props? You know, whips or leather boots?"

As with most sketch comedy movies, not everything works. “Are Transvestites Homosexuals?”, in which a straightlaced husband (Lou Jacobi) is caught by his wife and friends cross-dressing, is unfunny throughout, and feels twice as long as a result; uncharacteristic for Allen, the denouement of this little story is downright terrible. “Do Aphrodisiacs Work?” isn’t bad, only guilty of not being quite as funny as it ought to be (Allen plays a court jester who tries to seduce the Queen, played by Lynn Redgrave, until he’s thwarted by her chastity belt). A segment inspired by Kinsey-style sex studies shares the same fault, until, unexpectedly, it transitions from a Frankenstein parody (with John Carradine as the mad doctor) into a brilliantly ludicrous giant-monster film, with an enormous breast terrorizing the countryside, and Allen racing to stop it. (In one moment, he confronts it with a crucifix while it squirts milk at him.) With some comic momentum at last building, we move into the final, strongest sketch, a look at the inner workings of the male body during foreplay and intercourse. Allen plays a reluctant sperm, and Tony Randall and Burt Reynolds are stationed in the command center, acting like they’re in a WWII submarine thriller. So the film ends on a high note, and with a true climax (see also: The Kentucky Fried Movie).

Victor (Allen) helps the police capture a giant rampaging breast in a giant brassiere.

Oddly, the 2000 DVD of the film, released as part of MGM’s first Woody Allen Collection box set, features a still on the back cover of a scene which is not actually in the finished film: a skit about a black widow devouring her mate, with Allen and Lasser in spider costumes. (The scene was dropped when a suitable ending couldn’t be devised.) The sketch is not included as a supplement, and the disc is as bare-boned as all Woody Allen DVDs, offering only the theatrical trailer. At least it’s in anamorphic widescreen. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex seems, in retrospect, like a stepping-stone to more ambitious filmmaking from Allen. It’s not as consistently funny as Take the Money and Run or Bananas, but his experimentation here plants the seeds for the high-concept experiments to come: Sleeper (1973), which uses science fiction and Buster Keaton-style comedy as its satirical tools; Love and Death (1975), mimicking Ingmar Bergman and David Lean as he takes on Russian literature; all leading to the breakthrough of Annie Hall (1977) and the emergence of his own unique voice as a filmmaker. It took making a comedy about a sex manual to loosen those limbs.