She – apparently filmed in 1982 but not released until 1985 – opens with a quote from H. Rider Haggard’s source novel, “In Earth and Skie and Sea/Strange Thynges Ther Be,” which apparently is all the impetus writer/director Avi Nesher needs to throw the novel out the window and let his freak flag fly for one hour and forty-five minutes. Well, She had already been filmed a few times before, to varying degrees of faithfulness (my review of the 1965 version is here). Perhaps it was time for the “Road Warrior meets Conan the Barbarian” approach, with a soundtrack of heavy metal music. Following a semi-animated opening sequence apparently meant to represent the destruction of the Earth by nuclear war (there’s a grim reaper with a scythe, a skull, etc.), we’re told it’s “YEAR 23: AFTER THE CANCELLATION.” Yes, the term this film uses for the nuclear annihilation of the planet is the same used for The Single Guy‘s premature departure. Little explanation is offered for just how the world came to be what it is now – there’s a cute reference later, when a character says, “What’s a bomb?” – but somehow it’s only taken twenty-three years for everyone to start wearing Masters of the Universe costumes, begin using horses as a primary mode of transport, fight only with swords and chainsaws (guns, for some reason, no longer exist), divide into factions and start worshiping their rulers as gods, and, for certain lucky ones, develop magical powers through the wonders of nuclear radiation. Also, Kellogg’s cereals and Mountain Dew go for top prices at the market.

Tom (David Goss) is forced to walk the "Path of Blood" by She and her followers.

In that market, called “Heaven’s Gate,” our heroes, Tom (David Goss) and Dick (Harrison Muller Jr.), are assaulted by a band of mounted thugs wearing clothing from a costume shop’s bargain bin (football helmet, Roman centurion helmet, magician’s cape, etc.), the only unifying theme being quite a lot of swastikas. Tom’s sister, Hari (Elena Wiedermann), is kidnapped in the struggle, but he seems relatively unaffected in the next scene, as he and Dick casually pick up a prostitute. The prostitute slips a mickey into their food, and delivers Tom to her goddess, “She,” played by dancer-turned-actor Sandahl Bergman (Conan the Barbarian). Tom is tortured by being dragged blindfolded through “The Path of Blood,” an obstacle course of sharp wooden stakes; then he’s abandoned to die in the wasteland. Luckily, he’s soon rescued by a jolly British scientist (named Tark, the ending credits inform me) in a cavern laboratory filled with smoking flasks, who engages Tom in some Standard Issue Fantasy Movie Exposition™, as seen in every Sci-Fi Channel Original Movie.

TOM: Who are you?

TARK: Your Fairy Godmother! So you’ve survived the Path of Blood. You’ll probably be seeking revenge now.

TOM: I’ve gotta find my sister.

TARK: Sister? She would never harm a woman.

TOM: It wasn’t She. There were men. Not even Nukes. Their leader was all dressed in black.

TARK: You must mean the Norks. Well, they’re awful too. But if they’ve got your sister, well, you might as well forget about her.

TOM: Why?

TARK: Because you’ll never reach Nork Valley. And even if you do, you’ll never come out alive.

“Tark” informs Tom that only She knows the way to Nork Valley, and promptly disappears from the film, never to be seen again. But what was he doing with those smoking flasks? Where did he get all those dogs? Why does he have a pillar covered with pictures of centerfold girls? Why does he keep pushing up his glasses between each line reading? One assumes that Tark’s abrupt appearance and departure is setting up some big return in the finale – say, showing up with an armored tank during the final battle, at just the critical moment (“Look, it’s Tark!” “Yes, your Fairy Godmother returns. You didn’t think I’d forget all about you, my little rapscallion?”); sadly, this does not occur.

She (Sandahl Bergman) battles a centurion in a post-apocalyptic junkyard beneath her temple.

Tom reunites with Dick, who was held captive in a pigpen (Circe-style) by the evil prostitute. Tom takes the time to punch the prostitute (“nice shot,” says Dick, patting him on the bicep). While they stage their next move, we watch as She endures a trial set in a cavern filled with barrels, televisions, crates, and assorted detritus spray-painted with phrases like “Military Hardware,” “Ajax,” “CIA,” “Hell,” and “From New York.” It looks like an ill-conceived project from the Work of Art TV show. Out of the crates spring armed centurions and medieval knights (I ask: how long have they been in those crates? Who’s feeding them? How do they go to the bathroom?), whom She has to defeat in combat; her last opponent is a giant robot Frankenstein monster, which suggests that perhaps this film was written by an NES game designer. In a tunnel behind the junkyard, the bloodied She encounters an oracle who urges her to bathe in the healing waters of a spring. “You have passed through the cycle again, goddess. But the prophecy still stands. A man will come to claim your heart. For him you will break your vow. Through him, you will be destroyed.” Remember these words, because none of them come true. At all. As the plot progresses, Tom and She do not fall in love. She isn’t destroyed. So let’s just move on and forget all about this oracle, shall we? One gathers it was really just an excuse to have a Sandahl Bergman bathtub scene.

Tom and She battle a tribe of doo-wop-loving werewolves.

Shortly, Tom and Dick kidnap She, and ride with her into the woods, where they encounter the Nukes – radiation-afflicted mutants wrapped in surgical tape and so fragile that when She pulls on the arm of one, it comes off easily (“I told you that would happen,” he says). Still, they do have chainsaws, and attempt to execute the trio in a trash compactor. Shanda (Quin Kessler), She’s loyal female companion, brings a cavalry of Amazonians to defeat the Nukes. She takes pity on Tom and Dick and points the way to Nork Valley, leaving them to find their own way. Then the goddess discreetly follows with Shanda (the stated motivation: “I’m curious”). In the forest the two men uncover a colony of young men and women draped in togas and wearing laurel leaves on their heads, reciting poetry (other daily activities: stroking their faces under umbrellas, and playing harp music next to a swimming pool filled with balloons). In the evening, they dine while listening to 50’s doo-wop tunes on a record player. “This is what the world used to be like before the Cancellation,” says their young leader, accurately. Tom and Dick think they’ve found paradise; but while the tribe sleeps, they turn into werewolves, and awaken in a ravenous fury. She and Shanda arrive in the nick of time, swinging their swords against the army of Eddie Munsters.

Godan (Gregory Snegoff) unleashes his powers.

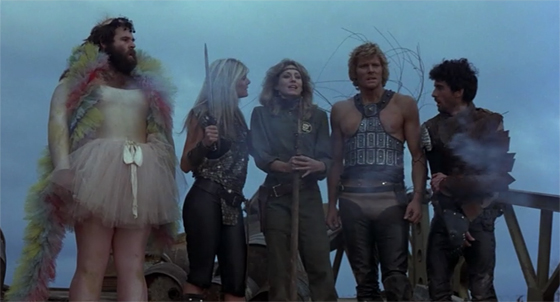

Because it’s been a good five minutes since anyone has been captured, the gang rides a few miles down the road into the theocracy of Godan (Gregory Snegoff), where they are immediately captured. Godan – whose image adorns dozens of Communist-style posters hanging around the village (the cult’s logo is a variation on the hammer and sickle) – is a man whose god-like powers come from his glowing-green eyes, which make a Hypnotoad noise while sending his enemies flying through the air. Tom and Dick heroically pretend to be disciples, while She and Shanda are taken into the dungeon to have their sweaty, scantily-clad bodies whipped. Godan is eventually undone by his backstabbing priestess, who buries an axe in his chest, while he simultaneously uses his powers to strangle her with the pull-cord of a curtain; everyone else just stands by and watches ineffectually while this occurs. And so our heroes travel on – just a little further down the road, where they’re captured. This time the culprit is a mad scientist and his assistant, a bearded giant in a ballerina outfit. (A detail from She previous adaptations left out.) Another daring and improbable escape ensues. But all of this is just preamble to what I would regard as the film’s most compelling and unequivocally successful sequence. A bridge leading over a minefield and into the Nork fortress is guarded by an eyepatched man who looks like Rip Taylor and is dressed in a cross between a sailor’s uniform and a Daniel Boone costume. While he paces back and forth at the foot of the bridge, he imitates Groucho Marx, Howard Cosell, the Cowardly Lion, James Cagney, and Popeye; he also creates new characters on-the-spot such as “the British guy” and “the gay hairdresser.” In other words, he’s Robin Williams. And, just like Robin Williams, if you try to dismember him, those severed parts only grow into more copies of Robin Williams, until you are facing an army of Robin Williams and there is nothing to do but submit.

An army of Xenon clones (led by David Traylor).

When confronted by this menace (actually called Xenon, and played by David Traylor), Tom does what comes naturally: he starts swinging with his axe. But as the Xenons begin to multiply, and a cacophony of celebrity impressions begin to carry down the bridge, only one solution remains (as She is left to discover; Tom doesn’t waste his time trying to solve any problems): lift them up and hurl them over the side, onto the mines, exploding them one at a time. What I am saying is that this is a very emotionally satisfying sequence. Your requisite 80’s post-apocalyptic sci-fi climax follows, as seen in Spacehunter: Adventures in the Forbidden Zone (1983) or Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn (1983), only not in 3-D and more poorly staged. After a battle with the Norks (led by Gordon Mitchell), Tom rescues his sister and departs across a river on a raft. Sandahl Bergman merely stands there, watching, as a brief image of the oracle is transposed over her face. Perhaps this was a reminder to the audience that there was this prophecy, an hour earlier, which didn’t actually come to pass. Perhaps this was the editor reminding the director/screenwriter that there’s a plot hole they forgot to fill; we can never be sure. Avi Nesher, who filmed this in Italy, continues to direct films in his native Israel; his most recent is The Matchmaker (2010). It is the world’s loss that he has not revisited the works of H. Rider Haggard.