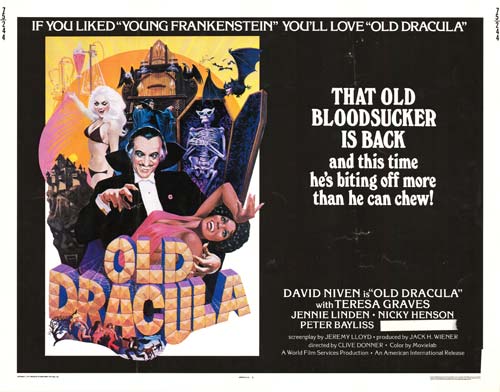

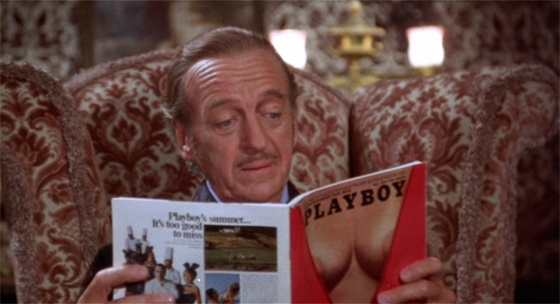

There’s a hint of a good idea buried somewhere in Old Dracula, aka Vampira (1974): what if Dracula were still around to enjoy his pop culture success? How would he adapt to international celebrity? The opening scenes hold some promise. Dracula – played here by David Niven, who looks very much like David Niven and not very much like Dracula at all – is lounging in his castle, reading an issue of Playboy and leering at the veins and jugulars on display. His assistant, Maltravers (Peter Bayliss, The Magic Christian), arrives with a glass of blood and proudly announces the vintage:

“It’s a ’63. The daughter of a French businessman who came to use our telephone when his car broke down.”

“Oh, the virgin? There’s not much of that left.”

“No indeed, sir. But I’m sure you’ll find the ’71 – you know, the climbing accident – will still have a lot of body in it.”

“Pity, it’s more than we can say for him.”

I would have enjoyed 90 minutes of this coolly-delivered banter from Niven and Co.; but, alas, Old Dracula soon proves it’s not going to be that kind of movie after all. I was not complaining, however, when Linda Hayden showed up in the castle sporting an unbuttoned top and a clumsy German accent. My crush on Linda Hayden is well documented in these pages. It’s also the reason why I now own a DVD of Old Dracula, against all reason. Hayden – who played the love interest in Confessions of a Window Cleaner the same year – is her usual fetching self, playing the hired help who’s accidentally turned into a vampire by Dracula when he tries to stop her from quitting. This leads to an amusing scene in which Dracula entertains his guests – Playboy playmates gathered for a Castle Dracula photo shoot – while trying to prevent the newly-vamped Hayden from biting everyone. Alas, he shortly dispatches her with a crossbow to the heart. Vampires are too much upkeep.

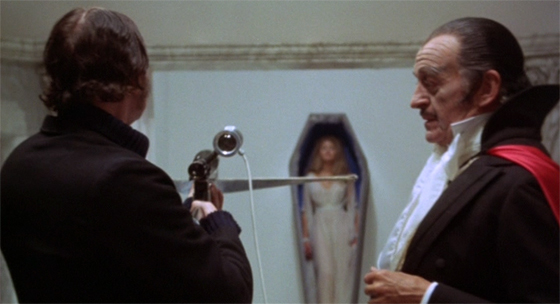

Dracula (David Niven) assists his servant Maltravers (Peter Bayliss) in exterminating an unwanted vampire (Linda Hayden).

Dracula’s real goal is to revive his dead wife Vampira (Teresa Graves, of the TV series “Get Christie Love”). He hopes that such a wide variety of beautiful Playboy bunnies will provide at least one blood sample that matches the type he needs for his transfusion. After drugging the women and drawing samples, he finds what he’s looking for; but, shades of “Abby Normal,” Maltravers has gotten the samples mixed up, resulting in Vampira becoming black. (The study will be published in the next issue of The Scientific Journal of 1970’s Comedy.) Though all the expected racial gags will follow, I do begrudgingly admire how the revelation is first handled: “I’m black,” she says, and Dracula responds, “Very.” “It’s beautiful!” she says, and he smiles back at her: “Yes, black is beautiful.” You’ll forget the moment a few minutes later when Maltravers is awkwardly explaining how the experiment was like mixing colors in with your whites (“Bringing my wife back to life is not like doing the laundry!”) – but still, the moment is there. Soon enough she’s beginning to pick up some hip urban slang and dragging him to a screening of Jim Brown’s Black Gunn. He acts the dutiful husband and doesn’t complain.

Marc (Nicky Henson) poses amidst some Playboy bunnies for a Dracula-themed photo shoot.

Sadly, he does seek to restore Vampira to her original state, chasing down each of the Playmates and stealing more blood samples with the help of a writer named Marc (Nicky Henson, There’s a Girl in My Soup) and some fake vampire teeth he hypnotizes Marc into wearing, by some plot mechanics that might charitably be called convoluted. You won’t be paying that much attention to the plot, because there are too many familiar faces popping up every few minutes: Freddie Jones and Veronica Carlson of Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed; Carol Cleveland of Monty Python’s Flying Circus; Jennie Linden of Women in Love; and assorted other hard-working British character actors from film and TV. But the early scenes of the film, which successfully translate a kind of Mad Magazine flavor of campy puns and bawdy humor, falls away all too quickly as the tone shifts into something more serious. It’s bizarre. Soon enough we’re being asked to care about Marc’s plight to save his girlfriend from Dracula’s clutches, while he battles the urge to strangle women, implanted by Drac’s hypnosis. Instead of the chaotic, slapstick payoff you’d expect from all-star comedies of this era, you get something that’s merely chaotic: a funk-addled 70’s costume party that drags on endlessly. The only reason to endure is a disorienting final gag that you will not easily forget: David Niven in blackface. That, and the theme song “Vampira,” sung by the Majestics and written by none other than Anthony Newley. His lyrics for “Goldfinger” are a tad more memorable.

Dracula enjoys an issue of Playboy in his castle.

The film was released under the title Vampira, but hastily retitled Old Dracula in the States to draw associations with a certain Mel Brooks film. The comparison is unflattering. Clive Donner – who directed What’s New Pussycat (1965) in better times – does a competent job, which means this production looks a lot more professional than the Freddie Francis-directed Nilsson vehicle, Son of Dracula (1974). (There are interesting sets and some clever visual gags, like a collapsible travel coffin that Drac provides his wife.) The British film industry struggled throughout the 70’s, and sexploitation – the only surefire route to profit – was the rage. Old Dracula received a PG rating in the U.S., but would perhaps be more successful with an R. What’s the point of constantly invoking Playboy and boasting a large cast of attractive young women if the discreet glimpses of nudity are fleeting? (My best guess: to hook a wider audience.) Sexploitation, or at least a more complete ribaldry, would have granted the film a sense of purpose. As it is, Old Dracula isn’t nearly as much fun as it ought to be.

(Available now as a burn-on-demand DVD from MGM’s Limited Edition Collection. The anamorphic widescreen DVD looks very good.)