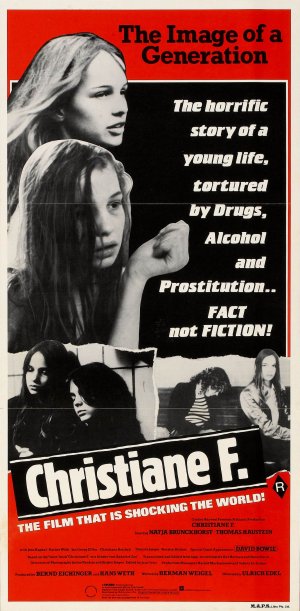

Christiane F. (aka Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo [“We Children of Zoo Station”], 1981) is the tale of Christiane Felscherinow, whose true story of drug addiction and prostitution at the ages of 13-14 was published first as a series of interviews in a German news magazine, and then as a bestselling autobiography in 1979. An exposé of teenage life on the streets of Berlin from one who survived and escaped, it was a sensation with an audience curious to uncover the seamiest details of Germany’s urban youth culture. The inevitable film adaptation was from Uli Edel, a young, first-time director who would go on to direct Last Exit to Brooklyn (1989) before translating his gritty style to television dramas such as Twin Peaks, Homicide: Life on the Street, and Oz. His work on Christiane F. is admirably unadorned. Though the subject matter anticipates films like Less Than Zero (1987), Trainspotting (1996), and Requiem for a Dream (2000), Edel’s film is deliberately straightforward, occasionally uncinematic, like a fly-on-the-wall documentary. As Edel explores restroom stalls, decaying train stations, and crowded dance clubs, the camera’s gaze is unflinching; it’s a film about locking eyes with those you would normally cross the street to avoid.

Christiane (Natja Brunckhorst) and her boyfriend Detlev (Thomas Haustein) feed their habits.

To tell the story of Christiane F.’s harrowing downward spiral, Edel enlisted a cast of young – mostly underage – amateur actors. Natja Brunckhorst was only 14 when she was hired to play the role of Christiane; Thomas Haustein, playing her boyfriend Detlev, doesn’t seem to be much older, judging by his hesitant brush of a mustache. As with Taxi Driver, this is a gradual descent into an urban Hell, and the unfamiliar faces of the johns and junkies leaning against graffiti-sprayed walls and slumped against toilets only add to the film’s verisimilitude. The texture helps considerably since the story itself is fairly mundane: Christiane, increasingly isolated from her broken family, takes some LSD with friends while lecturing those who shoot up heroin. But soon enough she’s curious to try some herself, which leads quickly into addiction, and ultimately into turning tricks for cash, just like her boyfriend, who confesses to hustling for a gay clientele on the side. It’s a vehement anti-drug film, but one which is coated with a viscous layer of bodily fluids; the scene in which Christiane, following a lengthy and brutal withdrawal, suddenly sprays her boyfriend – and the bed, and the walls, and their last remaining drugs – with rust-colored projectile vomit surely ranks among the most spectacular, and nauseating, anti-drug statements ever committed to film.

The zombie-like Christiane stumbles through the streets of Berlin.

The withdrawal scene also features a moment in which Christiane, delirious, begins clawing off the room’s wallpaper, like a scene in a horror film (symbolically, the innocent, colorful design of her childhood wallpaper peeks out from behind the shreds). It’s significant that early in the film Christiane takes her date to a screening of Night of the Living Dead, for by the film’s end she exists in a world inhabited entirely by Romero-esque zombies, and has become one herself; her mother’s horror at finding her overdosed on the floor of their bathroom mimics the horror of the mother from NOTLD who discovers that her daughter has transformed into a monster (the very scene Edel excerpts in Christiane F.). But the scene which most closely evokes that of a horror film is firmly rooted in real-world terror: while Christiane shoots up in a public toilet, a junkie comes climbing over the closed door of the stall, stealing the needle from her, and plunging it into his throat, indifferent to the blood that streams loose. He returns the needle a minute later, says his thanks, and leaves.

David Bowie performs "Station to Station" for an enthralled Christiane.

David Bowie was sympathetic to the film’s cause, and produced the film’s soundtrack, which contains songs from his late-70’s period (Station to Station, Low, Heroes, and Lodger). He also appears as himself in concert, mesmerizing the Bowie acolyte Christiane with his performance of “Station to Station” (in the parking lot outside the concert, she snorts heroin for the first time). The original Germany vinyl release of the soundtrack album was fetching $60 at a local records store as of a few weeks ago, but you can find the 2001 CD remaster for much cheaper. Although it contains no exclusives to the Bowie catalog, it remains my favorite album of his, with a mood that swings wildly between ecstasy and gloom – a perfect match to Christiane’s drug-induced highs and Lows. It also contains the bilingual version of “Heroes,” in which Bowie sings part of the song in German. That track is a highlight of the film Christiane F. – accompanying a Godard-esque sprint by the juvenile delinquents through a closed mall – just as it’s a highlight in Christopher Petit’s strange, overlooked mood piece Radio On (1980).