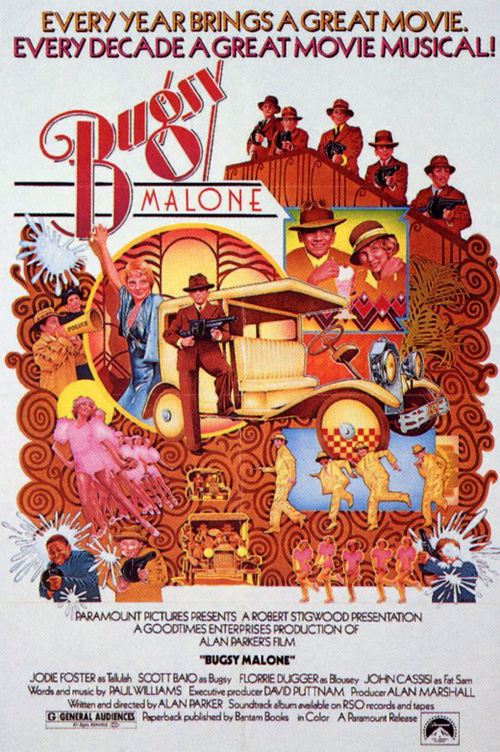

I had no idea. I mean, when I was a kid, Bugsy Malone (1976) was just that really odd movie that was on HBO quite a lot. The one with Scott Baio and Jodie Foster, both of them still adolescents, in a cast full of adolescents, all playing dress-up in a Prohibition-era gangster musical. I’d pretty much forgotten about that movie – or perhaps doubted it really existed, and wasn’t just a figment of my childhood imagination – until I stumbled blindly into the “Tomorrow” segment of the movie when turning on the TV one morning at 6am in college. What a random thing to encounter: a young black child mopping the floor of an empty speakeasy with Paul Williams’ voice coming out of his mouth, then mournfully slow-dancing with a young girl. It took a few minutes for it all to come back to me. Oh yes. Splurge guns. But I had no idea, none at all, that while this film had been lapsing into the furthest recesses of my memory, it had garnered far more than a cult following in England. Here, at the 2012 Wisconsin Film Festival launched Wednesday night, Stephen Kessler, the director of the new documentary Paul Williams: Still Alive (2011), introduced the revival screening of Bugsy Malone by noting that it was so big in the U.K. that there’s a “Bugsy Malone Camp” where kids go to perform the musical. I was under the impression that the film was never released on DVD – well, not here, but in the U.K. it’s been released on Blu-Ray, and the soundtrack is still in print. There’s also a cast album from a more recent musical adaptation, which has gushing reviews on Amazon and iTunes – but not so much of the album itself: “I played Fat Sam in my school’s production of this classic. The music is great.” “I am in the play as the opera singer and my best friend is Blousey…if your [sic] trying out for Blousey here are some tips. 1. SING LOUD…” “I’m in the musical this spring and I’m gonna play Tallulah. The people on this version sing very good, but I’m looking for the movie with Jodie Foster in it.” “Well, I was in Bugsy Malone last fall, as Dandy Dan (yes I am a girl…lol).”

"Bugsy Malone" Lobby Card, with Jodie Foster (right) as Tallulah.

So there seems to be kind of a High School Musical/Glee phenomenon happening around Bugsy Malone, which isn’t really that surprising if you consider that the songs by Williams are ridiculously good, in particular the closing number, “You Give a Little Love,” which is of a piece with his work for The Muppet Movie (1979). Williams was on a roll back then. While writing the music for Bugsy, he was also working on A Star is Born (1976), for which he’d win the Oscar for Best Original Song with Barbra Streisand (the AM radio favorite “Evergreen”). But Bugsy Malone feels like a follow-up to Brian de Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise (1974). The rock musical/horror parody allowed Williams to write a soundtrack aping a variety of musical genres (glam, heavy metal, country, surf rock, etc.) in a grand satire of a soulless music industry. Bugsy Malone, being a period picture, has a more specific musical focus – the Roaring Twenties – and provides the singer/songwriter the opportunity to more fully explore a particular style (there’s quite a bit of Cole Porter in here). And, like Phantom, it’s just strange enough in conception that it could only have been made in the 70’s, destined for poor box office and future midnight movie status. But, again, I’m incorrect: though no blockbuster, Bugsy Malone did quite well on its initial release. Somehow, kids found it – and they’re still finding it. And that’s great, because it’s for them.

"Bugsy Malone" lobby card: from the climactic, cream-filled shootout.

Supposedly, the decision to use an all-child cast (most everyone is under the age of 14) was suggested by director Alan Parker’s son. The decision certainly sets the film apart as one of the most unique children’s films ever made, though that choice leads to other choices, in a snowball effect of cinematic eccentricity: these kids sing with adult voices, usually that of Paul Williams; they drive pedal-operated cars; and instead of firing Tommy guns, they throw pies and use a high-powered “splurge gun” which splatters their faces with thick white cream. Should you get pummeled by the splurge gun, you’re considered dead for all narrative purposes. The plot is pure 30’s gangster-picture formula: there’s a war on between two rival mobs, one led by Fat Sam (John Cassisi), the other by the very British, very mustached Dandy Dan (Martin Lev). Caught in the middle are Bugsy (Baio), a charming but apathetic Humphrey Bogart type, Blousey Brown (Florrie Dugger), who’s pursuing a singing career, and Tallulah (Foster, on her way to stardom already thanks to Taxi Driver), a flirtatious flapper. The plot is meandering and, frankly, not that compelling. The same could be said about a lot of musicals. This was Parker’s first feature, and he takes great pleasure in both sending up genre clichés (note the over-the-top reaction of Fat Sam to the accidental death of his henchman Knuckles) and staging – with a greater sincerity – the many dance numbers. Later he would take the cinematic musical into even more experimental territory with Pink Floyd: The Wall (1982) – for which he would court a completely different audience.

Director Stephen Kessler in a post-film Q&A for his documentary "Paul Williams: Still Alive" (2012 Wisconsin Film Festival).

A word about Paul Williams: Still Alive. The documentary was shown the same night as Bugsy Malone at the Wisconsin Film Festival (both will screen a second time on April 21) – a sort of “Paul Williams Night,” if you bought tickets accordingly. Director Stephen Kessler was on hand to present both films; Williams sent his blessings but couldn’t attend. Kessler’s unconventional documentary eschews the traditional point-by-point bio, instead following the filmmaker and his subject as they travel from one unglamorous gig to the next: hotels, casinos, and, ultimately, the Philippines, where Williams draws a much larger audience. Kessler adores his subject, but finds Williams to be prickly, withdrawn, and frequently uncooperative – until the trip overseas, when he finally begins to open up about his traumatic childhood and his struggles with alcoholism and substance abuse in the 80’s. Williams eventually permitted access to boxes and boxes of forgotten VHS tapes sequestered away in a storage locker, and Kessler sprinkles the findings throughout the film: among them, an absurdly dramatic shootout on Police Woman; appearances on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show (one in which Williams sits on the couch in his Battle for the Planet of the Apes makeup – the result of too many banana daiquiris, he quips); a skydiving stunt for Circus of the Stars; and, disturbingly, some self-made home movies from his years lost to substance abuse. Sober for the last couple of decades, he’s now a happy family man and president of ASCAP, protecting the rights of other songwriters. Some may protest that Kessler doesn’t take a more detailed and informative look at Williams’ career (his 60’s work is barely touched upon, and there’s no background info given on Phantom of the Paradise, Bugsy Malone, or The Muppet Movie), but his approach reveals a more personal and complete portrait of Williams as a human being, and the result is unexpectedly touching.