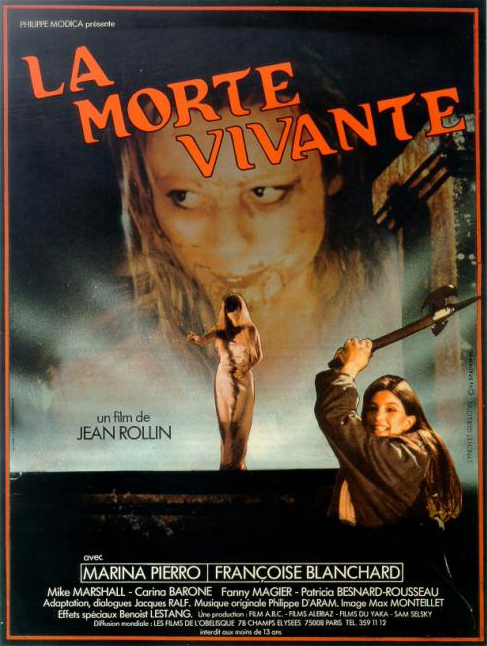

Being a fan of Jean Rollin is sometimes like being a fan of Philip K. Dick. There are works that are essential, and others that were dashed-off during an evening to pay the rent. If you were to introduce someone to the artist’s work, you’d want to be careful about what you select. You’d rather have someone new to PKD reading Ubik or A Scanner Darkly than Vulcan’s Hammer; and when it comes to Rollin, you’d rather they not start with something like Schoolgirl Hitchhikers (1973). Better they choose The Living Dead Girl (La morte vivante, 1982), for one example. Even though it’s slightly atypical, taking a few steps in directions heretofore unexplored in Rollin’s filmography, it’s a remarkable little B-movie, one considerably more serious and unnerving than what he’d attempted in the 70’s. As a zombie picture, it’s leagues beyond the mediocre Zombie Lake, which he’d only made the year before; a newcomer wouldn’t even guess they were by the same director. His heart was in this one. That’s what matters. Yet they are both zombie movies, on the surface, and there are suggestions in Zombie Lake of what was to come: namely the sub-plot of the undead German soldier who tenderly reconnects with his daughter (the film’s one redeeming feature, which still played ludicrously). The Living Dead Girl develops this idea into a larger theme about devotion to reviving a shared memory – and the dangers of doing so.

Catherine Valmont (François Blanchard) is reanimated and feeling a new kind of hunger.

The film opens with a shot of endless gray factories, the kind of industrialized modern landscape that Rollin last criticized in Night of the Hunted (1980): anathema to a director obsessed with realms more natural and ancient, such as chilly beaches, overgrown countryside, old chateaus, and decrepit cemeteries. The image proves to be shorthand, for the first characters we meet are two workers driving into the country to bury some chemical waste. (With magical properties, as is so often the case in genre horror. What caused a disease of amnesia in Night of the Hunted on a different continent gave birth to the Toxic Avenger.) The catacombs where they’re storing the barrels just happen to border a crypt – with lit candles, of course – that is home to two women of the wealthy Valmont family who recently passed, a mother and her daughter. Sliding naturally into the role of grave-robbers, the two lift the lids of the coffins on the hunt for jewelry. But one of their barrels leaks, and the daughter, Catherine (François Blanchard), is revived by the toxic liquid, quickly slaughtering both men, drinking their blood and gnawing on their flesh. All of this is standard-issue zombie fare. But Rollin’s camera rarely leaves Catherine’s side. He follows her out of the crypt and into the country, until she reaches the chateau where she once lived. We see her walking from room to room, dwelling on a piano and a music box. She begins to remember. A flashback shows a prepubescent Catherine with her best friend, Hélène (Marina Pierro), partaking in the skin-pricking blood-brother ritual so common among young boys. “If you die, I will follow,” they tell each other. The now-grown Hélène coincidentally phones the estate, and Catherine answers. The undead Catherine cannot speak, but she plays the music box. Hearing the familiar music, Hélène calls Catherine’s name. She somehow knows.

Marina Pierro as Hélène, guardian of the undead Catherine.

Much of what follows pays further tribute to the tropes of the genre. While our protagonist kills some more – in the tradition of 80’s slasher films, she murders a couple post-coitus – a tourist and amateur photographer (Carina Barone) captures her on camera walking through a field, and begins to suspect she’s somehow the recently-deceased Catherine Valmont. But all these scenes are mere distraction while Rollin builds a plot worth caring about. Soon enough Hélène is reunited with Catherine, and when she finds her best friend surrounded by bloody corpses, she makes a hasty decision to hide them. She cleans up Catherine and helps her learn how to speak again – and her first word is Hélène’s name. She kills a pigeon for Catherine to eat, but it’s not good enough: her friend needs to eat a person. When we next see Hélène by the side of the road, pretending to be stranded and looking for a lift, you can see where this is going, but you’re unlikely to take your eyes off the screen. As the story progresses, a strange transfer seems to take place. Catherine begins to speak with greater ease, and expresses remorse and disgust with her own actions. Hélène becomes accustomed to killing, and eager to keep her blood-sister well fed. What is most shocking about The Living Dead Girl is that it begins in such a paint-by-numbers fashion (grave-robbers, toxic waste, reanimation) and progresses to a finale that is genuinely lyrical in the best Rollin fashion. It is also, simultaneously, brutal and heart-breaking. (Note how Rollin excruciatingly depicts cannibalism, then finally pulls his camera far, far back, distancing us from the carnage. I was reminded of the fascist who turns his binoculars around to look at his victims through the opposite end in Pasolini’s Saló. But Rollin’s technique also emphasizes the loneliness and isolation of poor Catherine.)

Catherine follows her instincts.

Redemption and Kino Lorber have been doing such a great job of issuing Rollin’s films to Blu-Ray that I’ve yet to have the time to really dig into the voluminous special features on their discs, and The Living Dead Girl has more than most. Fitting, since it’s such a fine and unusual horror film. The Blu-Ray was released last year alongside his 1997 Two Orphan Vampires, with liner notes by Tim Lucas comparing the films. My only complaint is that the cover art depicts the blood-soaked climax of the film, which happens to be a spoiler akin to that Planet of the Apes DVD release with the Statue of Liberty on the cover. Not to mention that it makes for an unattractive design, when more intriguing images from the film could have been used. But Jean Rollin is all about marginalized appeal: too much blood and sex for the critics, and too much contemplative strangeness for most horror fans. What makes The Living Dead Girl so haunting is that it sinks its teeth more deeply than your average zombie movie. In its treatment of a worthy theme – the longing for an innocent past that can never be recaptured – with some bloody, bloody metaphors, it’s a horror film that resonates with emotion, and to accomplish the feat it doesn’t need a horde of zombies, but only one of them, and her anguished cry that ends the picture.