As a longtime Alice fan, I was always interested in seeing the 1933 Paramount Studios version. (At least, in the Leonard Maltin Movie Guide, its cast made it sound like an interesting, large-scale production.) My first (partial) viewing was completely unexpected. We were dining and drinking with some friends at a local brewpub. One of this pub’s more distinguished features is that at least one or two of its televisions are always playing Turner Classic Movies. This night, which was a few months ago, TCM chose to air the 1933 Alice in Wonderland in their Friday night prime-time slot, and looking up from my beer I could easily identify the film: it was so faithful. There was Alice (Charlotte Henry) stepping through the looking-glass and playing with the living chess pieces. There was Alice falling down a rabbit hole, and always being the wrong size to get through that little door. My eyes widened: they’re doing the Mouse and the Dodo Bird and the Caterpillar in full costume. I knew what film this had to be, but the first thing you have to know about this take on Alice in Wonderland is that it’s a singular experience with the sound muted. What should be wondrous and childlike becomes a David Lynchian journey populated with disturbing makeup and imagery, something you feel ought to be synched up to Dark Side of the Moon, if nobody’s gotten around to trying that combo yet.

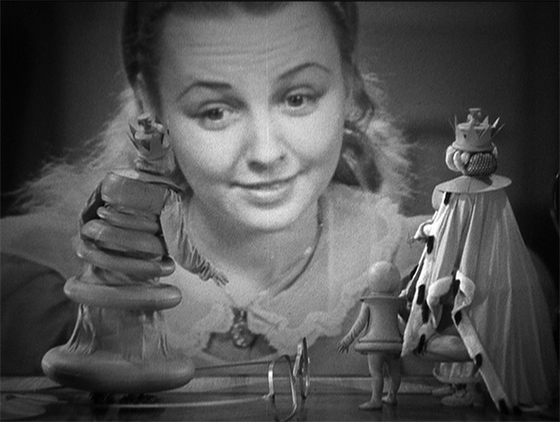

Charlotte Henry, as Alice, declares to her chess pieces that she is not a volcano.

Knowing I could disregard this film no further, I let it jump toward the top of my to-do list: Must…watch…with sound. Luckily, there’s a DVD. Not a very good DVD – it was clearly a rush job to accompany the release of the 2010 Tim Burton film – but a DVD nonetheless. The print is a little rough and worn, but this is pretty much what you’d expect from a film of the early 30’s, and short of a major restoration, this is fine, and worthy to add the collection of every Alice fan. Why? Well, because it’s faithful, for one, although it commits the common and minor sin of importing dollops of Through the Looking-Glass into Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. (This particular plot-merging is intelligently done and seamless.) But more than that, this is a film that was intended be a studio spectacle, with an all-star cast, elaborate costumes, an animated sequence, and almost nonstop special effects. Paramount and director Norman Z. McLeod, veteran of Marx Brothers films (Monkey Business, Horse Feathers), really wanted to do Lewis Carroll up right. And talk about prestige: the adaptation, which faithfully carries over absurd and satirical dialogue from the books, is by Joseph L. Mankiewicz and William Cameron Menzies, who have both ascended into Hollywood legend; Menzies is said to have worked on the art direction for this film (uncredited), and it would be a waste of his talents if he did not. Dimitri Tiomkin, near the beginning of his illustrious career, provided the score.

Alice encounters the baby-beating Duchess (Alison Skipworth).

But there is another reason this film is essential to Alice completists. The filmmakers are faithful to the books to such a degree as to produce a very interesting effect. McLeod, Menzies and Co. actually try to reproduce with exactness the illustrations of Sir John Tenniel, and you could hold up the books beside the screen and see the exact same compositions mirrored in live action. This is where the grotesque makeup finds its role. The Duchess – whom, it’s surmised, Tenniel modeled after the 16th century Quentin Matsys painting The Ugly Duchess – becomes a monstrous figure when played by an actor on a set buried inside an enormous misshapen head that resembles poured oatmeal. (And oh, how those little human eyes inside that head blink at you, while the long mouth twitches open and closed – you will be haunted.) It’s enough that for some reason they are adapting this passage at all. Carroll delights in the sadistic nature of his Duchess, who roughly shakes a little wailing baby while declaring that she beats him when he sneezes – a condition exacerbated by the Cook, who is constantly tossing clouds of pepper throughout the Duchess’ home (and smashing plates). This was already a somewhat disturbing, if comically exaggerated, passage in Carroll’s book, but it’s the stuff of nightmare in live action. Similarly, Tweedledum and Tweedledee are meant to resemble Tenniel’s originals, but come out looking like something by Gerald Scarfe from Pink Floyd The Wall. And perhaps it’s best not to dwell on the unmistakably phallic nature of the Caterpillar.

Alice and the Cheshire Cat (voiced by Richard Arlen).

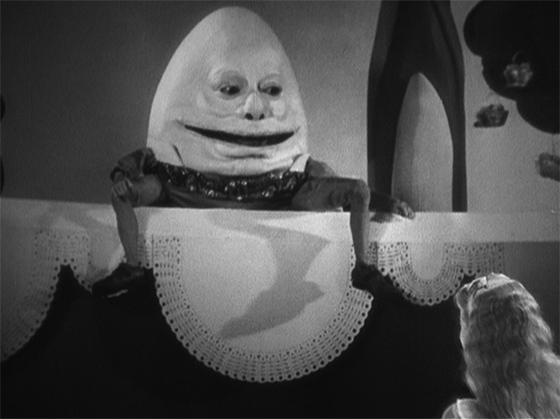

The truth is that Carroll is best suited for animation, but Walt Disney was still some years away from proving that a feature-length animation film was viable and could hold the audience’s attention. When he did finally get around to adapting Carroll, in 1951, it seems that he was partially influenced by the 1933 version, there being a very strong similarity between McLeod’s one animated sequence (“The Walrus and the Carpenter”) and the same scene in Disney’s, and the way that Carroll’s poems are adapted into song. Disney also hired Sterling Holloway, the character actor with the distinctive sleepy voice, to play his Cheshire Cat, decades after Holloway played Frog in the Paramount version. Holloway makes a more suitable Cheshire than Paramount’s odd choice of Richard Arlen, the contract player who starred in Island of Lost Souls (1932). But this adaptation trumpets its cast foremost, with opening titles that showcase the actors’ faces (in a storybook) along with the bizarre costumes that represent them. If they hadn’t done this, you probably wouldn’t have guessed that’s Cary Grant as the Mock Turtle; and though his face is at least visible, you might have a hard time recognizing Gary Cooper as the White Knight. Modern viewers are less likely to register names that carried more weight in 1933, such as comediennes Louise Fazenda and Polly Moran as the White Queen and Dodo Bird, respectively, comic actor Edward Everett Horton as the Mad Hatter, Busby Berkeley veteran Ned Sparks as the Caterpillar, or even, in a cameo, Baby LeRoy (born 1932), whose IMDB bio contains the sentence, “Once had his milk spiked with gin by W.C. Fields.” Fields himself is perhaps the most recognizable, for even though his face isn’t seen, he’s playing Humpty Dumpty. You know his voice, and who else would you cast in the part?

"I beg your pardon?" "I'm not offended, and it isn't respectable to beg." W.C. Fields as Humpty Dumpty.

The performer who makes the greatest impression is Charlotte Henry, who must rank as one of cinema’s more convincing Alices (notwithstanding my wife’s complaints that Henry’s a little too old for the role). She is every bit as studiously polite, occasionally indignant, and alternately delighted and alarmed as one would hope an Alice to be. But here Alice has wandered into a deeply strange Wonderland, inadvertently darker and more disconcerting than some of the more Goth interpretations of recent years. By delivering such a literal treatment of Carroll’s material with early-30’s Hollywood “magic,” the film accidentally presents a creepy acid trip – even with the sound turned up and the jaunty Tiomkin music playing; by the time Queen Alice is being introduced to her leg of mutton, a smiling puppet swaying on two spindly legs (and resembling one of the California Raisins), there is nothing to do but submit. “How do you do? Ha ha ha ha,” it says as it spreads its little arms wide and closes its eyes. The unsatisfactory mutton is replaced by a large pudding with eyes. As Alice cuts into it with her knife, it declares, “How would you like it if I cut a slice out of you, you creature?” Feed your head, Alice. Feed your head.