No one knows who her father was. But 17-year-old Anna (Angharad Rees, Poldark) has been living in the house of a medium, who happens to double as a Madam. After she tries to sell Anna’s virginal body to a sleazy politician named Dysart (Derek Godfrey, The Abominable Dr. Phibes), Anna refuses the man, and is nearly raped; when the medium interferes, something in Anna’s eyes seems to change, and she drives a poker through the woman and the door she’s pinned against. The only witness is Dysart, unless you count Dr. Pritchard (Eric Porter of Hammer’s The Lost Continent), who knows Dysart is still on the premises and catches a glimpse of his silhouette roughing up Anna’s in the window. Yet when Dysart protests to the police inspector that he wasn’t at the scene of the crime, Pritchard decides to say nothing. Instead, he adopts Anna into his home, convinced that she somehow committed the crime – though she doesn’t seem physically capable – and equally convinced that he can cure her of the homicidal impulse in her unconscious mind by applying the new methods of Freudian psychoanalysis. That’s when the bodies start to pile up. While Dysart tries to persuade him that the girl is possessed, and the good doctor uncovers evidence that Anna’s father might in fact have been Jack the Ripper – who killed her mother before her very eyes, a trauma whose imprint might explain her actions – Pritchard finds himself going to absurd lengths to cover for her gruesome crimes, all in the name of science.

Anna (Angharad Rees) watches a séance through bars - just like the bars on her crib from which she witnessed her mother's murder.

Hands of the Ripper (1971) is often cited as an anomaly of late-period Hammer horror, with elaborate, extravagant bloodshed reminiscent more of Italian giallo than the Hammer Gothic brand. But, like Demons of the Mind (1972) and Straight On Till Morning (1972), it also points the way forward for a studio maturing into a more adult decade for the genre – if only they could have financially endured it. Peter Sasdy directs, having also helmed one of the most interesting Dracula films, Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), the Elizabeth Bathory riff Countess Dracula (1971), and a couple episodes of the Hammer TV series Journey to the Unknown (1968). He makes the potentially laughable material feel serious and compelling, and resists the instinct toward broad satire which someone like Jimmy Sangster might have employed. And the story is absurd: Dr. Pritchard is obsessed with curing Anna by delving deep into her psyche, even while she continues to slaughter anyone who gets too close; he simply sweats a bit, ushers her away from the bodies, and continues his research. It’s nonetheless fascinating to watch Eric Porter’s performance as a psychoanalyst in denial of his own feelings: it is evident to the viewer that he is sublimating his own desire for Anna, even while he affects a fatherly stance.

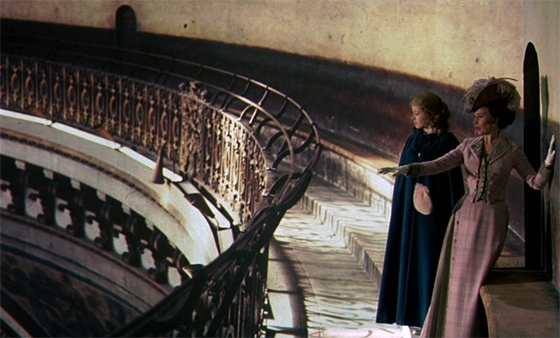

Anna and the blind Laura (Jane Merrow) visit the Whispering Gallery of St. Paul's Cathedral for the film's tense climax.

Sasdy also makes the most of the talented Rees, who signals the transition into trance and out again using only her eyes, and might as well have pulled a Christopher Lee and crossed out lines from the script, so effectively does she use her face. We are constantly being placed into her subjective point-of-view, as Sasdy cross-cuts the present with the trauma from her childhood. Just as the opening credits freeze-frame the key moments of her mother’s murder, so do those moments get underlined when Anna encounters echoes in the present: someone tenderly kissing her cheek (as her father Jack did), bars like those in her childhood crib, blinding reflected light. The director is at his most effective staging the moments of suspense and sudden violence. All of the murders are memorably played, especially the murder of a prostitute, with pins plunging straight through the hand which she holds up for protection, down into her face and eye (the sound effect here is particularly squirm-inducing). The final scene is what undoubtedly makes Hands of the Ripper such a favorite among Hammer fans. Here Sasdy channels Hitchcock, using a well-known landmark – in this case, the Whispering Gallery of St. Paul’s Cathedral – for the final confrontation between Anna and Dr. Pritchard, with the blind fiancée (Jane Merrow) of Pritchard’s son making a most sympathetic, helpless victim for the mesmerized Anna. The final moments before the end credits carry an emotional heft unusual for the genre. This could easily have been a silly, mediocre, or forgettable effort, but instead it’s well-acted, thoughtful, tense, and a praiseworthy addition to Hammer’s waning days.

The film is available as a Blu-Ray/DVD set from Synapse Films.