A film crew has come to the Beal House to shoot a horror movie about the murders which took place there generations ago: seven victims, shot, hanged, drowned, and stabbed. The veteran director, Eric Hartman (John Ireland, Red River), has brought with him a famous celebrity well past her prime, Gayle Dorian (Faith Domergue, This Island Earth), who also happens to be his on-again, off-again lover. She has qualms about the macabre project and the eerie old house itself, and he struggles to convince her to spend the last remaining nights on the shoot – even after her beloved cat is found mysteriously chopped in two. Meanwhile, actor David (Jerry Strickler), the boyfriend of the film’s blonde starlet, Anne (Carole Wells, Funny Lady), finds the Tibetan Book of the Dead sitting on a shelf and becomes obsessed over the text, particularly an apparent incantation to raise the dead; as though it were the Necronomicon, he makes sure to read it aloud, and twice. If that weren’t foreboding enough, the caretaker (John Carradine, enjoying himself) sleeps in an open grave out back that’s dug beside the buried seven. His name is Price. (“What’s his first name? Vincent?” “No. Edgar.”)

Faith Domergue reenacts a black magic ritual, the image of a decapitated cat on a mural behind her.

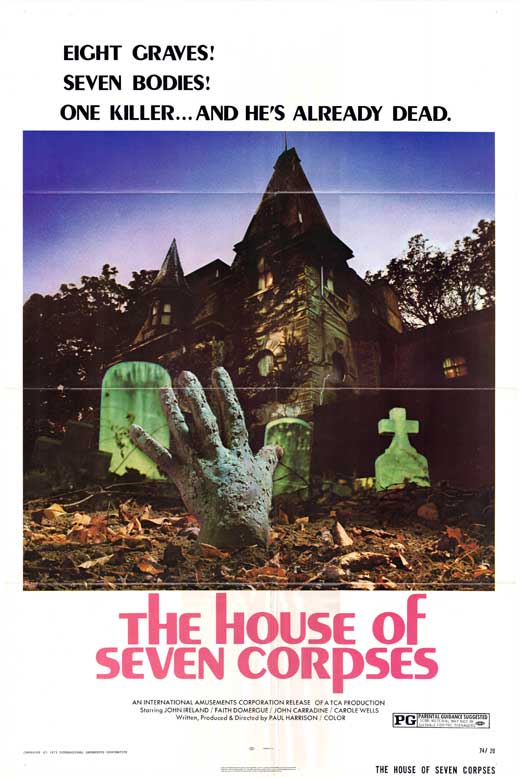

The House of Seven Corpses (1974) is a charming, if minor, zombie picture, the sole feature film from TV director Paul Harrison. It was shot almost entirely in a single location, the Utah State Historical Society, formerly the governor’s mansion (as associate producer Gary Kent recalls on the Blu-Ray’s commentary track, the head of the foundation during the filming was a fellow named “Joseph Smith”). The three-story house is really the star of the picture, claustrophobic but with a dizzying central staircase that Harrison makes the most of, aiming his camera above and below the gracefully-curved railings: several of the scenes consist of characters calling up or down at one another while separated by two floors, a nice visual symbol for the chaos and frustrations of the crew’s attempt to organize the movie-within-the-movie. The film takes its time, revealing its monster only when the movie’s nearly over (he’s a blue-skinned, foot-dragging zombie who, smitten, bears Carole Wells off toward the water like he’s the Creature from the Black Lagoon). Luckily, the script and characterizations are amusing enough to make this more of a pleasure than a chore. This is an early example of a horror movie that’s about horror movies, something more novel in the early 70’s than today (the premise has now become pretty tired, the fun Cabin in the Woods notwithstanding). Reading the Tibetan Book of the Dead, David comments to Anne, “It may be garbage, but it’s better garbage than the writer gave us.” Harrison continually pulls the rug out from under us. The opening depicts a faux black-magic ritual with Domergue and a mural of a cat’s head impaled on a pitchfork – and he cheats here, since he uses a (not-very-good) special effect that could only be achieved post-production. An older, vain actor named Millan (Charles Macaulay, Blacula) appears in several scenes before he suddenly removes a wig and false moustache, revealing his true features. We witness the behind-the-scenes snipes and fights and catty little comments. When a man is stabbed by a collapsible knife, we see the blood-pump worked by an effects artist standing right behind him. To make it all the more meta, some members of Hartman’s film crew are members of the House of Seven Corpses crew; the man playing the snarky makeup artist is Ron Foreman, the film’s actual makeup artist and the art director for films such as Rocky III (1982) and The Ice Pirates (1984).

The zombie, invading the set, prepares to put an end to both the director and his film.

The meta-framing produces some strange and unintentional side-effects. Although we see a montage of “real” murders over the opening credits (the various deaths of the Beal clan, seemingly inspired by the opening of Robert Wise’s The Haunting), most of the film depicts killings that are staged, and the filming of those scenes is sometimes so prolonged that we start to wonder if someone will really be injured or killed while the cameras are rolling (in other words, we’re waiting for something to happen). Finally, when David sees Gayle screaming in the middle of a take and says, “Wait, this is real!”, he lifts up the top half of the bisected cat, which looks to us like nothing more than a stuffed animal: fake, really fake. It’s enough to make the head spin. Of course, the irony is fully intentional when the zombie starts murdering our horror movie-makers, but I wasn’t particularly invested in the film’s stated theme of the present mirroring the past. Although that’s one thoughtful and efficient zombie, killing off the crew so quickly and in the manner of Beals gone by. Where’s the deleted scene where the monster hurries to the next crime scene while panting, “Oh yeah, now I gotta drown somebody”? The film is now available from Severin Films (who will shortly be releasing 1976’s The House on Straw Hill). I suggest pairing this with a Polygamy Porter on a Saturday night.