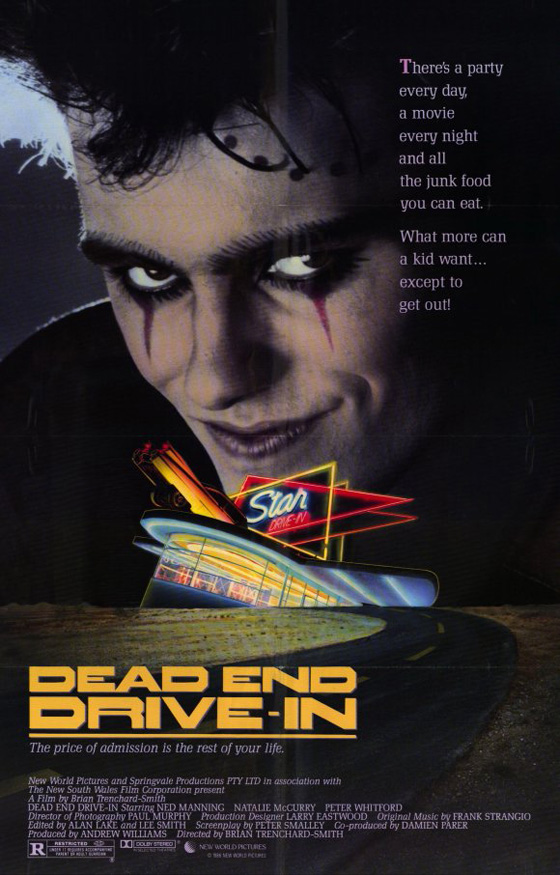

The premise of the Aussie B-movie Dead End Drive-In (1986) works best if you’re blind to it going in – as I was. I only knew this film as a fading VHS box in the science fiction section of all the video stores that have now boarded up their windows, gone the way of the drive-in theater. My assumption was that the film involved a gang of punks on the rampage – as much I gathered from the cover, with its leering teenage boy in eye makeup and the glowing neon sign of the film’s main setting, the Star Drive-In. It didn’t look science fiction enough for my tastes, nor Mad Max enough – just very 80’s. So when Crabs (Ned Manning) – so named because he thought he had them once, only he didn’t – drives his hot date Carmen (Natalie McCurry, Cassandra) to the Star for a night of sex and cheap exploitation movies, I shared his ignorance for what was lying in wait. What promises to be another Road Warrior knockoff, with its opening scenes of rampaging “Cowboys” dressed in punk and new wave regalia, out of nowhere becomes, well, something closer to The Exterminating Angel (1962), as Michael Wilmington pointed out in his largely glowing L.A. Times review. Buñuel’s surrealist classic is about a dinner party in which the upper-crust guests find themselves inexplicably trapped, though they are barely conscious of the problem; gradually they begin to suffer and starve. Dead End Drive-In, directed by the prolific Brian Trenchard-Smith (The Quest, Night of the Demons 2) and adapted from a short story by Peter Carey (who co-wrote Wim Wenders’ Until the End of the World), offers a more logical explanation for the trap that is the Star Drive-In (for one, the fence is electrified), but not at cost to the film’s satire, which is front and center.

Crabs (Ned Manning) and Carmen (Natalie McCurry) try to find a primo spot at the Star Drive-In.

The opening sketches out its post-apocalyptic landscape, which looks much the same as every other science fiction movie of the 80’s. Some captions that highlight key moments of the global collapse between 1988 and 1990 end with the syntax-free summary: “Inflation, shortages, unemployment, crime wave/Government invokes emergency powers.” (It might as well add “et cetera, et cetera.”) We meet Crabs, a wiry little fellow who lives with his Italian mother and bodybuilder brother, Frank. Frank agrees to take Crabs along on one of his salvage rides, where he hunts down fatal car accidents so he can claim the spare parts – a major commodity in the crumbling city. Crabs envies Frank’s ’56 Chevy, and steals it for his date with Carmen. The “Security Road” to the Star is sealed by a gate with a sign that warns “No Pedestrians,” a detail which becomes the film’s entire premise. Admission is $10 for adults but only $3.50 for the unemployed, so Crabs lies to get the cheaper rate – unaware that he’s actually volunteering himself. While he’s having sex with Carmen in the back seat, thieves steal two of his wheels. Half-dressed, he tracks them through the parking lot, only to discover they’re actually police officers. He reports the crime to the Star’s manager, Thompson (Peter Whitford, Strictly Ballroom), who genially suggests they spend the night and tackle the problem in the morning. But the Star in daylight is a very different place: a prison camp whose prisoners are resigned to their fate, for their cars, too, have been stripped of vital parts, and there’s no walking permitted on that high-security road to freedom. Thompson sees great potential in Crabs as someone who can climb the ranks at the Star (and possibly replace him as warden someday), but the kid is frustrated that his fellow prisoners – society’s undesirables, the unemployed and minorities that arrive by the busload – only want to spend their time eating hamburgers, doing drugs, and watching cheap movies (some of which come from Trenchard-Smith’s filmography). He plots to restore his wheels and escape, but he grows frustrated with his girlfriend’s lack of initiative. Making new friends and enjoying all the perks offered the permanent residents, she sees nothing wrong with staying. She even joins the drive-in’s newly-formed white supremacist movement, to Crabs’ dismay.

Crabs attempts to break free of the drive-in.

The film’s best rug-pull is to establish the punkish gang members as snarling villains – one even has a bestial, dubbed growl – before we realize that they’re not the perpetrators but the victims. (There’s a fantastic tracking shot where we see the residents of the Star waking up in the morning, crawling out of the trunks of their modified, graffiti-splattered vehicles, laundry hanging up to dry between the cars – the film has fantastic production design.) Considering that George Miller’s first two Mad Max films established punks as gangbanging psychopaths, it’s particularly amusing that as soon as an influx of Asians arrive, paranoid-racist rumors begin to spread that they’re going to start raping all the women (never mind that most of these new inmates appear to be elderly, frail, and confused, having been rounded up by some xenophobic government policy). Meanwhile, middle-aged manager Thompson appears to be the friendliest and most trustworthy at the story’s outset, but proves, of course, to be in the government’s pocket, and is in fact the distributor of the drugs that mollify the inmates. The only sympathetic character is Crabs, who isn’t even all that bright (long after he’s been trapped, he’s still worried about what Frank will think about the damage to his car), but at least is conscious of the injustice surrounding him. Dead End Drive-In becomes a commentary on Australia’s dark past – a dumping-ground for the unwanted, and a stew of violence and prejudice – which places it in the same wheelhouse as District 9 (2009), a film that used the SF genre to comment upon South Africa past and present. But the satirical net is cast wider, relevant to anyone in danger of becoming prisoner to comforts and therefore subject to manipulation (see also: Edgar Wright’s The World’s End, now in theaters). This is the sort of pill that’s easiest to swallow when there’s gratuitous sex, violence, car chases, and eye-popping 80’s fashion statements: social therapy from the world of Ozsploitation.