Throughout September I’ll be spending A Month at the Grindhouse, taking a look at a handful of the disreputable, distasteful, violent, sexy, shocking, and mind-melting films that helped define the term. And really, post-Tarantino and Rodriguez (whose collaborative film I love, by the way) the word has been abused in recent years. Hell, Eighty Eight Films in the U.K. has been releasing DVDs under the banner “Grindhouse Collection,” but with many titles that went straight from Charles Band’s office to Blockbuster and Cinemax (Beach Babes from Beyond: not a grindhouse movie). I don’t pretend to be an expert on the subject. I was too young to have indulged in the grindhouse era, and lived far from the sorts of theaters to show such entertainments. The films I tend to review on this website are more drive-in than grindhouse (admittedly, many of these films played both), and I realize that’s where my tastes lie. I prefer monster movies with cheap makeup to The Last House on the Left (1972); but that won’t stop me from heading down to our virtual Forty-Second Street for a month’s worth of mayhem. I’m going to be the nervous little mark who’s wandered into the Rialto out of numbskulled curiosity for what those outrageous titles on the bright marquee could possibly be attached to. The selections I’m choosing, the majority of which I’m watching for the first time, were partly inspired by Bill Landis and Michelle Clifford’s Sleazoid Express (2002), partly on Michael Weldon’s Psychotronic film guides that were always at my bedside throughout college, or otherwise just titles chosen out of my own personal interest. Now, we’ve got to start somewhere, so it might as well be at the hands of Olga.

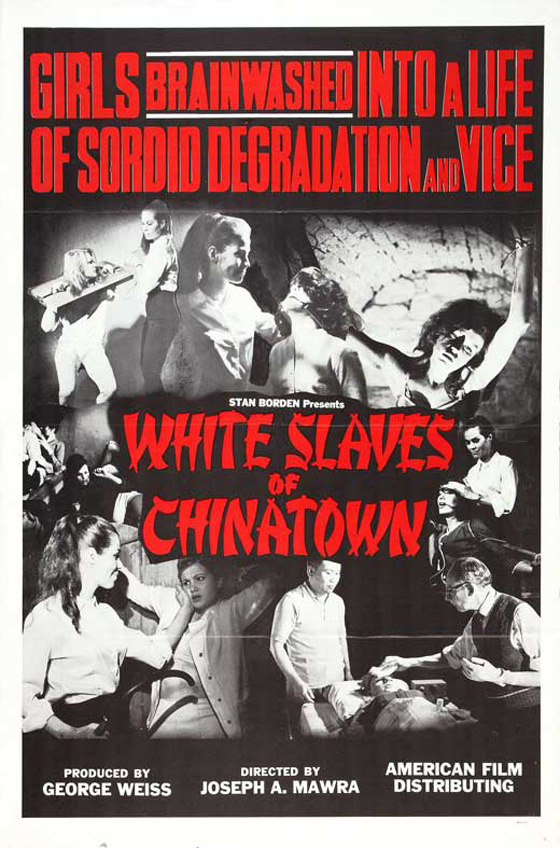

Just another one of the "White Slaves of Chinatown."

The two films I chose to kick off this marathon of the perverse are actually non-sequential films of the same series, the “Olga” pictures, which sprung from the fevered imagination of exploitation producer George Weiss (Glen or Glenda, Paris After Midnight). With his director Joseph P. Mawra, Weiss crafted the films economically and breathlessly – releasing them rapid-fire in 1964 – yet the films linger obsessively over every little detail, and it’s the details here that matter. These are fetish films. More to the point, these are S&M films, albeit of a comparatively gentle variety to what’s readily available on the internet these days. And it’s here that I must stop and state that S&M isn’t my thing – not to distance myself (to each his own), but to explain why I’m so ill-suited to the task at hand. To review a fetish film when one does not have that particular fetish is a bit like a vegetarian appraising the steak house that just opened up the street. But I’m not into feet and I love Buñuel (and steak), so let’s have a go. White Slaves of Chinatown (1964) is actually a strangely beautiful little picture, but in an accidental kind of way. I would not walk away from the film declaring Weiss and Mawra to be artists, but it is that obsession, that attention, that fixed gaze in gorgeous black-and-white, which creates something hypnotic for the viewer, regardless of one’s proclivities. The film was shot without sound, then given a stock soundtrack (Chinese music and some Fantasia selections: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice and Night on Bald Mountain) and some industrial film-style narration. “Few people dare venture beyond the honky-tonk and gaily-lit main streets of Chinatown,” says our stern male narrator, “but the few who do will surely take their fates into their very own hands, and perhaps even their lives.” The film runs 70 minutes, which is quite a lot to endure in a narrative film without any dialogue. But consider that the plot doesn’t matter. This is a film of images.

"'Please, Jimmy. Please help me,' she cried." The narrator expresses what isn't evident on-screen in "White Slaves of Chinatown."

Specifically, it is a film of bondage images, and scenes of the “white slaves” being hustled about, tortured, given opium to smoke, and eventually broken and remade as prostitutes. (If this sounds like a downer, that’s because you’re assuming this film takes place in a world resembling reality. You’d be wrong.) The criminal mastermind of this operation is Olga, played by Audrey Campbell, whose credits include Joe Sarno’s early sexploitation films Lash of Lust (1962) and Sin in the Suburbs (1964). Campbell, thanks largely to her role in the Olga series, became something of a dominatrix icon (she died in 2006); her legacy was to burn that archetype into celluloid for others to emulate. She doesn’t scowl that much; her expression is often one of smug satisfaction. She enjoys what she does. After she finally gets the independently-minded Elaine to grovel at her feet – what passes for a narrative arc in the first Olga film – she grins, arms crossed, while her voice-over declares: “Yes, even this stubborn and proud girl had to come round to my way of thinking sooner or later. Now I knew that I had won and she was mine.” She ties up girls in dungeons, whips them in silhouette, puts a French girl named Frenchie in a yoke crosspiece, and in one scene burns a cigarette into a girl’s breast, depicted from the POV of the breast – I suppose – as the cig comes closer and closer to the camera. In fact, it all does feel a bit Un Chien Andalou, though not by design. As the narrator keeps droning on, his uselessness becomes apparent in one completely surreal scene of disconnect. While Elaine drops her head into her arms, slumped at a desk, defeated, our faceless narrator clumsily reads off lines for her. “Elaine thought she heard something. Yes, it’s her friend Jimmy, he would help! But no, he doesn’t look the same, something’s happened to him. ‘Please, Jimmy. Please, help me,’ she cried. ‘No Jimmy, no, don’t! You don’t know what you’re doing! God help me.'” What we see is: Elaine looks up slowly, placidly, stares forward. A man enters the room. He kisses her on the cheek. He grabs at her more violently, overtaken by his lust, then drags her off. Meanwhile, nobody’s lips have moved through the entire scene, so our eyes tell us that no dialogue has transpired. Not to mention that the one-take narrator has finished reading his lines before “Jimmy” has even touched the girl. (His under-the-breath delivery of “God help me” is priceless. It sounds like his personal reaction to the script he’s been handed.) So when I say the film has an accidental beauty, and accident surrealism, this is what I’m talking about; though there is something genuinely skillful, in a cheap exploitation kind of way, in the film’s depiction of an abortion. We see the surgeon (Weiss himself, in a cameo) spreading the woman’s legs and then folding up her dress incrementally, deliberately – again, with a touch of fetishism; fold, fold, fold – before the camera cuts to black, the girl’s modesty intact, the fingers still making those little encroaching folds.

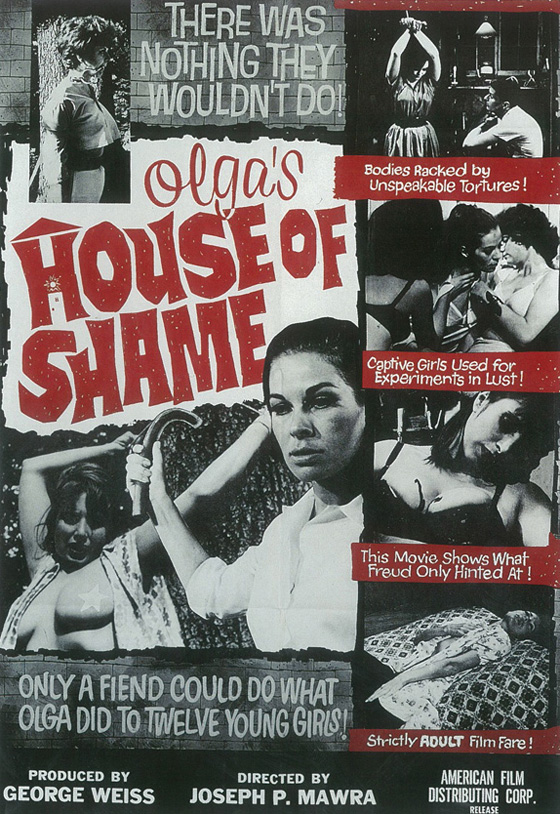

Olga (Audrey Campbell) tries to learn the whereabouts of some missing jewels in "Olga's House of Shame."

The endless Mussorgsky playing on the soundtrack is, on the one hand, lazily applied: one gets the impression that no one has the energy to change the record, so they keep resetting the needle instead. But it adds to the strange student-art-film aesthetic the film has stumbled into. White Slaves of Chinatown is the sort of film that could be played in an art installation on an endless loop as the backdrop to whatever, and it probably has. Olga’s House of Shame (1964), a favorite of John Waters, is the third film in the series after Olga’s Girls (1964), but you wouldn’t notice you’ve missed anything. It shares the first film’s love of stark black-and-white imagery and Night on Bald Mountain. But here we finally have dialogue, if only in brief moments, as though mail-order microphones arrived halfway through filming. The sound has me missing the silence; like an early talkie, it’s poorly recorded and the lines are awkwardly delivered. (The writing is as awful as ever.) The film is blessed with the best title of the series; I would have loved to have seen the words House of Shame on the marquee while the poor souls file in beneath it. There is a rudimentary plot, once again involving a girl named Elaine (played by a different actress) and her defiance of Olga, here served by a henchman, both of whom talk like 30’s gangsters. Elaine is held responsible for some missing jewels. She’s dragged back to a compound by Olga’s thug, tied to a chair and interrogated.

Campbell in her dungeon.

Interruptions to this “action” come in the form of Olga’s girls bare-breasted and tortured, though the aesthetic is more Bettie Page/Irving Klaw bondage photos with a healthy dash of Perils of Pauline (girls are tied to a tree by thick rope) than anything too distressing; this, and there’s plenty of female belly-dancing, in which the lesbian Olga takes salacious delight. Eventually Elaine undergoes another collapse and rebirth, but instead of emerging as a call girl, she becomes an Olga-in-training, putting Olga’s henchman in his place by first teasing him and then rejecting his declarations of love, forming the dominant role in this new master/slave relationship. The film ends with Elaine treating a woman like a horse out in the woods, leading her by a rope leash and cracking a whip (both women wear high heels, one in a white dress and one in a blouse and tight skirt, adding to the oddness of the scene). The voiceover says, “Yes, this was a proud day for Olga. She had created Elaine in her own image and likeness. Now there were two of them, two vicious minds working as one, set upon the destruction of all who stood in their way by whatever means possible.” Reenforcing the debt owed to 30’s serials (White Slaves of Chinatown opens with newspaper headlines spinning toward the camera), the narrator promises the further adventures of Olga in Olga’s Garden of Terror, although the titles stubbornly read Olga’s Garden of Bondage. What actually followed was Mme. Olga’s Massage Parlor (1965) and finally, from a different “creative” team, Olga’s Dance Hall Girls (1966).

A victim is tied to a tree in "Olga's House of Shame."

The Olga movies are pure exploitation films. They’re not pornography, but they share its singularity of purpose. They’re meant to excite, stimulate, arouse. That’s why they went straight to the grindhouses – to be ground out as fresh meat to the masses – and became hits there. Lacking the fetish for watching women being placed in extreme discomfort or tortured, there’s no reason for me to watch or enjoy the films; they aren’t for me. I like my women non-submissive, tough, and seizing control of their circumstances, something more in the Russ Meyer vein (who was no stranger to publicizing his fetishes). But here’s Audrey Campbell as Olga – someone Russ might have liked. Consider how different the films would be – and how much more of a footnote – if it were a man in charge of the dungeon instead of our Olga. Her bold lesbianism and stern command of her operation offer a bizarre feminist counterbalance within these sweaty-palmed little films. She’s a dominatrix who dominates semi-nude women instead of men, but she’s the mistress-of-all-mistresses nonetheless. It also shouldn’t be overlooked that the films are tongue-in-cheek, and aren’t completely lacking in self-awareness. In conjunction with the 50’s/60’s pin-up style B&W photography and the stylish-by-necessity use of nonstop classical music, these films, designed to be disposable, instead stick in the mind like a dirty hypodermic.