“I’m giving a dinner party in two weeks for my daughter, and Mrs. Dupree said that you cater to just the type of thing I’m looking for. I want something unusual, something totally different.” Mrs. Fremont (Lyn Bolton), the woman speaking, is wearing a blood-red dress with a fuzzy white stole, white gloves, and a wide-brimmed hat draped in orange lace that seems to dominate the frame. She’s standing before the counter of the shop that bears the sign, in Orientalist letters, declaring FUAD RAMSES EXOTIC CATERING. The counters are decorated with cans: lots and lots of cans that look like dog food. A man (Mal Arnold) is leaning forward against the counter, paying too-close attention. He’s wearing a black suit, black tie, and dyed hair so shining-gray that it actually looks blue. His bushy eyebrows conspicuously match. When he speaks to her, his eyes keep drifting away and to the right, looking for all the world like Christopher Walken on SNL trying to find the teleprompter. His voice somewhat resembles George Takei’s. He suggests the birthday dinner be “the actual feast of an ancient pharaoh. It has not been served for five…thousand…years.” We suddenly cut to a close-up of the upper half of his face. His pupils are tiny, the lights behind the camera blasting them, and showing us every pore and blemish. This is his Chandu the Magician routine. We cut to the victim of this impromptu mesmerism, her red lips peeled back in a kind of grimace. “Yes, yes,” she says slowly, “we must do it.” He claps his hands and she snaps awake. “Your dinner will indeed be a success, Mrs. Fremont, I promise it,” he says, glancing hastily to the right between each word. “Things will be arranged just as the feast of the goddess was given five…thousand…years…ago.”

A reverie, depicting the ancient Egyptian "blood feast" to Ishtar, interrupts the film.

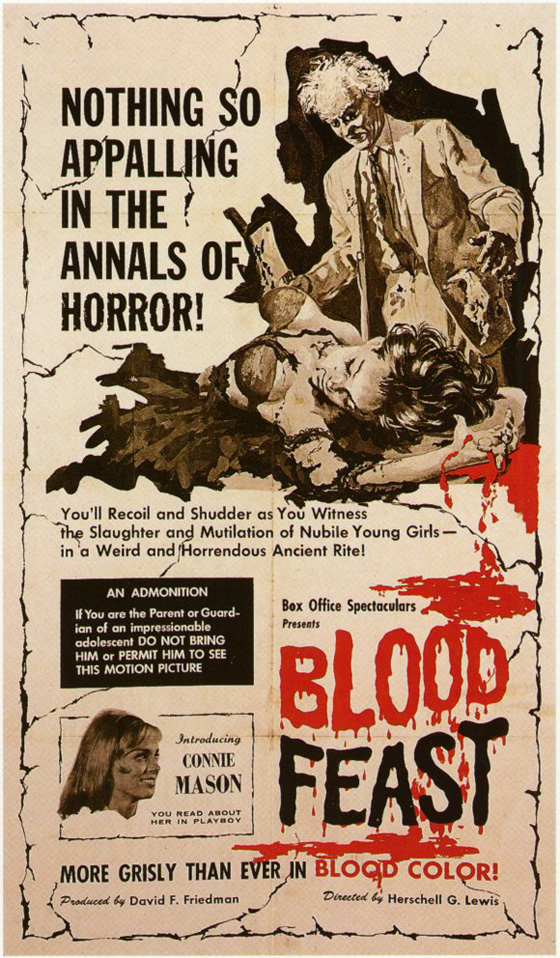

Welcome to the bizarre world of Herschell Gordon Lewis. Actually, he welcomed you a few minutes ago in an abrupt fashion that bears his unmistakable mark. Blood Feast (1963), celebrating its fiftieth anniversary this year, opens with a blonde woman in a bedroom listening to a Miami DJ describe the latest crime of a local killer: “Keep your door locked!” the tinny voice warns. She unzips her blue dress, stripping to an industrial-strength brassiere and the largest panties you have ever seen, which seem to go up to her breasts. The soundtrack (by Lewis) is a persistent, ominous thumping drum: BUMM…bumm…BUMM…bumm. We see a book lying on a bathmat: it looks like a leather Bible, but with the title Ancient Weird Religious Rites. The woman is now lying naked in the tub, barely concealed by the bubbles, naked except for her bright red lipstick. A shadow passes over her. It’s Fuad Ramses, holding a knife; down it comes, straight toward the camera, while he leers. It’s like the shower scene in Psycho (1960), with a few little differences, chief among them that we see the knife coming back up with some blood-dripping, unidentifiable, worm-like thing dangling from the end of it. We see the victim again, and her eye has been gouged out, blood running down her face. The camera pans down her inert body, a nipple peeking out from the suds. We now stand behind Ramses while he hunches over the tub and chops, chops, chops. Then he sticks a gory severed leg into his sack. Eat that, Hitchcock.

This happens.

What makes Blood Feast a cinematic landmark is not its five…thousand…years level of acting, but rather its buckets of blood and unidentifiable little red things that dangle at the ends of butcher’s knives. Art house imports had, for many years, begun to break down barriers of both violence and sex (as these films began to hit American theaters, the days of the Production Code were numbered). Hammer was already giving us oozing blood in vivid color beginning with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), but struggles with the BBFC kept the amount of onscreen gore limited. Blood Feast was in the grand tradition of road show exploitation cinema, in which envelope-pushing films, many of them with an ostensibly educational message (but featuring violence, sex talk, nudist camps, drug use, STDs, graphic childbirth footage, etc.) could keep a step ahead of the Production Code by hastily closing up shop and sprinting over to the next state after a week or two. But Blood Feast doesn’t have much of an educational message. It’s a sensationalist slasher film whose grisly aesthetic is borrowed wholesale from E.C. Comics and the Grand Guignol Theatre (appropriately enough, the Grand Guignol closed down one year before Blood Feast‘s release). Lewis’s innovation was a crude and obvious one, but it kicked wide the doors of the horror genre. Here began the splatter film. Here was born Fangoria and the more sadistic subsets of the genre.

Suzette Fremont (Connie Mason, at right) and friend, poolside.

“Give yourself up to the goddess!” screams Ramses as he slices up another victim. The film, the first of the informal “Blood Trilogy” – followed by Two Thousand Maniacs (1964) and Color Me Blood Red (1965), from the creative team of Lewis and producer David F. Friedman – is structured over a comfortable pattern. Ramses stalks a woman; Ramses kills her and takes as his prize a particular body part for his Egyptian blood feast; police detectives Pete Thornton (William Kerwin) and pipe-smoking Frank (Scott H. Hall) grow increasingly frustrated while sitting in their nondescript, echoey office (“Well, we’re just working with a homicidal maniac, that’s all!”). As the limping Ramses acquires each bloody organ, he stirs it into a smoldering pot before a statue of Ishtar, in a temple located in the back room of his catering store. The killings are a contradiction: they’re both messy and sterile (possibly because the appropriate squishy sound effects are strangely missing). The only one that strikes me as a bit uncomfortable – instead of just laughable – is one in which Ramses pulls out a girl’s tongue. He’s so long at the business, his back to the camera, his arm working furiously, that it’s hard not to squirm just a little bit, even if it’s just over the scene’s awkwardly dragged-out takes. Also awkward – but fascinating – is Lewis’s color photography, which looks exactly like early-60’s home movies. The Florida locations contribute to the something-we-shot-on-vacation feel, with ladies in bikinis lounging poolside (plastic flamingos stuck in the lawn behind them), a couple making out at the beach at night (“Relax, hon. Just a while longer. Your folks know you’re in good hands!”), or knife-wielding Fuad Ramses tearing off through green bushes under a baking sun. The climactic dinner scene looks like a Tupperware party, with makeup-laden housewives milling about the living room – and young Suzette Fremont (Connie Mason, Kerwin’s future wife) in the kitchen, happily coerced into a sacrificial virgin pose by the salivating, homicidal Ramses.

Suzette unwittingly prepares herself for sacrifice.

By any conceivable measure, Blood Feast is a pretty terrible film. The community theater-level acting isn’t well served by the script, though the dialogue lends itself well to drinking games: my suggestion is to take a swig anytime someone says Pete’s name to his face. (When Pete calls his girl Suzette, he announced into the phone, “It’s Pete Thornton,” as though she might be dating other Petes.) To the film’s credit, it does have a sense of humor about itself. When the cops figure out Fuad’s scheme, Frank barks, “Call the Fremonts! For Pete’s sake tell them not to eat anything!” (You can count this as a “Pete” for your drinking game, if you like.) After her daughter is rescued from being the main course, Mrs. Fremont says, “Oh dear. I guess the guests will have to eat hamburgers tonight.” Our killer’s end is particularly memorable, accidentally compacted in the back of a garbage truck. Frank says to the garbageman, “You just did this town the biggest service it’s ever had!” “Let’s go home, Frank,” says Pete, lighting a cigarette as Frank lights his pipe. They walk off, leaving the poor garbageman alone with his truck and a mutilated corpse. Cut to the golden statue of Ishtar, now weeping blood. Then THE END, over an image of the Sphinx, red paint dribbling onto the letters as if Lewis is standing right above them, squeezing out the last drops from the tube. That’s all we have left; it’s a wrap.