2008 marked the 20th anniversary of a TV show called Mystery Science Theater 3000. It also marked the beginning of a project called Cinematic Titanic, begun by a significant swath of the show’s creative personnel: creator Joel Hodgson, Trace Beaulieu, Frank Conniff, Mary Jo Pehl, and J. Elvis Weinstein. An anniversary celebration-slash-launch party was held at the Acme Comedy Club in Minneapolis. The festivities began with a preview of Cinematic Titanic’s first DVD, in which the gang, once more in silhouette, riffs The Oozing Skull (actually Al Adamson’s 1971 Brain of Blood). After a few minutes, the voices of MST3K‘s Dr. Forrester (Beaulieu) and TV’s Frank (Conniff) are heard bickering over the soundtrack, and the reel abruptly ends. It had been a while. Their familiar voices gave me chills. What followed were stand-up sets from all the performers, including a singalong of the MST3K theme song, and a rare opportunity to see Hodgson’s “gizmo” prop comedy and magic tricks (in the 80’s, he performed some of these gags on Saturday Night Live and Late Night with David Letterman). Conniff sung his “Convoluted Man” theme song. Weinstein made some dirty jokes. As became typical of the Cinematic Titanic events to come, a signing was held afterward, and not a fan was turned away. The project mutated slightly over the following years. At first the group released more DVDs like The Oozing Skull, copying the MST3K format to such an extent that there would even be pauses in the film to do little sketches (albeit with the performers still in silhouette). A loose-fitting concept was applied to the project: at the end of each “episode,” they would place the DVD into a time capsule called the “Time Tube,” a torpedo-shaped object that was lowered into the theater; their 2008 live show was called the “Time Tube Tour.” Those live shows were such a hit – frequently they found themselves playing large theaters to sold-out audiences of MST3K fans – that gradually the focus shifted to live performance. The DVDs became recordings of their live shows, and though I like the early DVDs too, what a difference an audience makes. (That, and the fact that you can see their faces in the live DVDs, just as you can in the theater. Watching the performers try to crack each other up adds to the entertainment value.) Now it’s five years later, and we’re upon the original show’s 25th anniversary. Cinematic Titanic, who in the last couple of years made it known they would only go to cities where they were invited (rather than actively marketing themselves), have decided to call it quits. They’re making the last round on a Farewell Tour, riffing movies like Ted V. Mikels’ 1973 film The Doll Squad.

The cast of Cinematic Titanic: Joel Hodgson, Mary Jo Pehl, Trace Beaulieu, J. Elvis Weinstein, and Frank Conniff.

Backing up a bit, for the uninitiated: Mystery Science Theater 3000 began as a public access show on KTMA, a UHF channel in Minneapolis/St. Paul, before being picked up by the fledgling Comedy Channel, eager to fill up large chunks of airtime and finding a natural fit with a show that featured bad movies being riffed by a stand-up comic and his two puppets for two-hour blocks at a go. I caught up with the show when my cable provider in the Milwaukee suburbs picked up the Comedy Channel, and I’m forever thankful they chose that station instead of its direct rival, Viacom’s Ha! channel. Watching The Comedy Channel meant I was blessed with the likes of Rich Hall’s Onion World, Night After Night with Allan Havey, Short Attention Span Theater (which introduced me to Monty Python as well as the budding alternative comedy scene), The Higgins Boys and Gruber, and, of course, MST3K. Joel Robinson (Hodgson), Tom Servo, and Crow T. Robot were into their second season by then; the first episode I ever saw was Jungle Goddess, a 1948 Robert L. Lippert production with George Reeves. As an adolescent with lots of time to kill, I was hooked (and I’m patiently awaiting a DVD release of Jungle Goddess, Shout! Factory). With his meta-puppet show, rife with obscure and not-so-obscure references to pop culture’s past, Hodgson had found the perfect blend of Saturday-morning-TV nostalgia and B-movie-love. After a switch of hosts (from Hodgson to head writer Michael J. Nelson), a brief trip to the big screen (Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie, just out on Blu-Ray), and a jump to another network (the Sci-Fi Channel), the show finally came to an end in 1999. Now the show is more popular than ever, thanks in large part to DVDs, Netflix, and YouTube, not to mention parents sharing it with their children. (It has puppets. What better way to get your kids into B-movies?) At Friday night’s Cinematic Titanic show in Milwaukee, a father and his little boy came dressed as Torgo and The Master from the MST3K episode Manos: The Hands of Fate. The kid wore a fake mustache and carried a staff with a hand stuck on the end of it. It was a thing of beauty.

Cinematic Titanic at the Pabst Theatre in Milwaukee.

I’ve caught CT live several times, and watched as they’ve settled into a comfortable, smooth-running show. After some crowd warm-up shenanigans by Dave “Gruber” Allen (an old Comedy Channel vet, of The Higgins Boys and Gruber), the show is divided into two halves: stand-up, then the movie. The September 20th performance was not a sentimental, fare-thee-well affair. Gruber, in tribute to The Doll Squad, performed his own riffs on Ibsen’s The Doll House, as read by Pehl and Beaulieu. (There are a few levels of meta there, including the fact that Gruber, with his snarky, “hip” jibes at boring old Ibsen, is essentially satirizing MST3K. Also notable: Pehl couldn’t keep a straight face.) During these sets there was no reference to this being a farewell tour, though I suspect it will be mentioned in shows to come. But there was something a bit touching about Hodgson’s set, which was a slideshow of photos from his childhood in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin. (The Midwestern origins of the show’s cast and writers always made those of us living in Wisconsin and Minnesota feel like the show was made for us. Regional riffs abound in MST3K.) Hodgson showed pictures of his family, a shot of his youthful grinning face, a B&W still to explain why Bucky (the mascot of the UW Badgers team) terrified him, and he outlined how his imagination was shaped by TV and the movies. (A helpful diagram explains how God gave them to us.) He offers a picture of Albert the Alley Cat, a puppet who actually co-hosted the weather reports on WITI Channel 6, as evidence that such a thing existed (“No one believes me when I tell them this”). A TV Guide cover (with the Hodgson address label stuck to it, and featuring a terrifying image of a screaming Lucille Ball apparently being attacked by a joyful Flipper) accompanies his explanation that he only figured out how to tell time by learning when his favorite shows were on, including Lost in Space, one of MST3K‘s inspirations. Then an intermission, and The Doll Squad unfolded in all its grimy and poorly-lit glory.

Sabrina Kincaid (Francine York) lunges at the villain with a sword. CT's riff: "Put your 3-D glasses on now!"

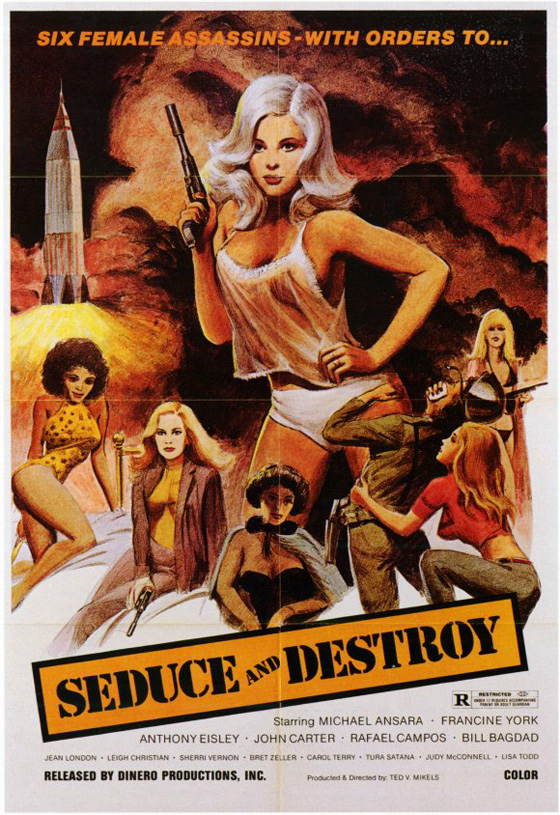

Hodgson actually took a moment to explain Ted V. Mikels before the film began: how he made his fortune on The Corpse Grinders (1971), which helped finance the construction of his castle (“Sparr Castle”) in Glendale, California, where he lived with dozens of women at a time, actresses who needed a place to stay. Much of The Doll Squad is shot there, and it looked less like a castle to my eyes and more like the country’s most sprawling Melting Pot Restaurant. The team of the title is a crack squad of shapely women summoned by a teletype machine to uncover a conspiracy led by Michael Ansara (at the time, Barbara Eden’s husband), which involves rats carrying the bubonic plague. (One riff notes that this is the only film that’s too poor to afford rats.) It’s difficult to follow the plot, and that’s not so much the fault of CT’s interruptions as it is the terrible sound quality of the film, which would have been better off dubbed. The head of the Doll Squad is Sabrina Kincaid, played by Francine York, whose breasts form the center of every mise-en-scene. Her squad features five other women, including – significantly, for cult-movie fans – Tura Satana, star of Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965), as well as Mikels’ The Astro Zombies (1968). (Hodgson on The Doll Squad: “It’s like a Russ Meyer film, only without the substance.”) Satana’s role is unfortunately small, though she does get to stand atop a vehicle and mow down thugs with a machine gun during the film’s extended climax.

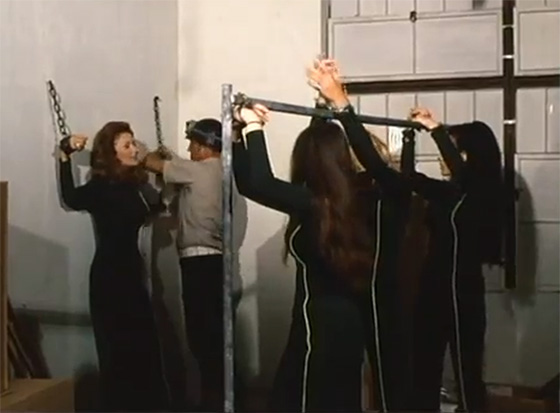

The dungeon where the Doll Squad is imprisoned; or, in CT's words, the inside of Frank Conniff's brain.

There’s no shortage of violence in The Doll Squad, a film that influenced Kill Bill and (probably/arguably) Charlie’s Angels. The plot setup is delivered while the characters are skeet-shooting (the exposition is constantly interrupted by shouts of “Pull!”). In one scene a female agent is shot straight through the head, an unexpectedly gory moment that made the audience gasp and then laugh. But what sticks in the memory, apart from the loud 70’s fashions and funky score, are the numerous explosions. Mikels’ technique is to superimpose the image of an explosion unconvincingly, and he leans on it hard. In the most uproarious scene, two gun-toting guards are detonated from the inside after they consume some vodka spiked with an explosive substance. They simply stand in place and Mikels slaps his cheap effect onto them. (For moments like these, no riff needs to be written. The audience is laughing too hard and too long for anything else to be heard.) Never mind that it doesn’t look real; for the finale, Mikels blows up the enemy base by repeating this effect over different shots of his house, which the Cinematic Titanic crew lends a patriotic musical accompaniment befitting a Fourth of July fireworks show. For all its violence, The Doll Squad decides to substitute cheesecake for sex, though Satana does get a rather revealing striptease (of which she’d be no novice), which is also a little bizarre; the curious can find it on YouTube (Satana’s spinning causes Beaulieu to complain, “My wiener is dizzy”). The climax, in which an endless army of guards are shot by the black-suited gals, would be a lot more fun if it weren’t so dark; still, though this takes place around midnight, in certain shots it’s broad daylight. There’s plenty here for Cinematic Titanic to take on.

It’s sad to see Cinematic Titanic go, though nice to have the opportunity to give them one last standing ovation. It was a good five years, and perhaps if the members lived closer to each other (apparently they’re now scattered across the U.S.) the project would continue. Certainly interest couldn’t be higher right now, with Shout! Factory releasing DVD sets of MST3K three times a year (a 25th anniversary collection is due this winter), and new groups of movie-riffers popping up, including Austin’s Master Pancake Theater and comedian Doug Benson’s Los Angeles-based Movie Interruption, in which he’s frequently joined by celebrity comics like Zach Galifianakis and Patton Oswalt. There’s also, of course, Rifftrax, the MST3K offshoot that predated CT and was founded by show vets Mike Nelson, Kevin Murphy, and Bill Corbett; they continue to release downloadable MP3s and pack movie theaters for their live Rifftrax broadcasts (the most recent being Starship Troopers). But I’ll always have a special attachment to CT, because I grew up with Joel Hodgson’s MST3K. I’m sure he’ll be back soon – he has a new live show, Riffing Myself – and I’ll take it as a significant hint that he asked the audience at Friday’s show to follow him on Twitter. In the meantime, keep circulating the tapes memories.