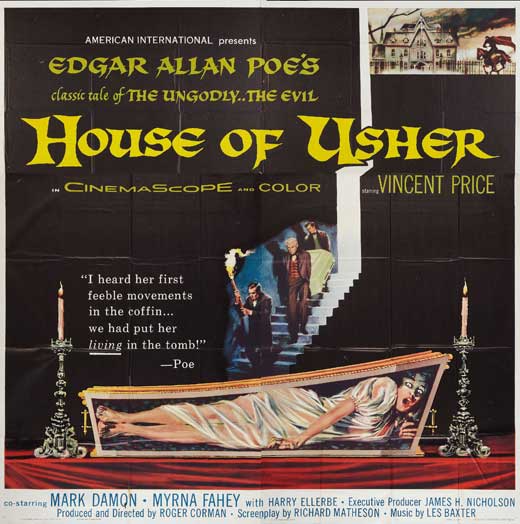

The new Blu-Ray box set The Vincent Price Collection is the jewel in the crown for Shout! Factory’s “Scream Factory” line. Thanks to a licensing deal with MGM, six Vincent Price titles formerly available as aging, often non-anamorphic “Midnite Movies” DVDs are given beautiful new high-definition transfers, allowing you to transform your living room into an ancient Victorian manor by the seaside. The titles in this set include The Fall of the House of Usher (aka House of Usher, 1960), The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), The Haunted Palace (1963), The Masque of the Red Death (1964), Witchfinder General (aka The Conqueror Worm, 1968), and The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971), all worthy titles to represent Price’s American International Pictures reign from the 60’s through the early 70’s, and excellent introductions to his brand of chilling (and occasionally cheeky) horror. Among the many bonus features are Price’s introductions to some of the films, taken from an Iowa PBS series from the early 80’s. In a nice touch, Shout! Factory gives you a viewing option to bookend the film with these comments from Price, exactly as though you were watching the presentation on PBS (only with much better picture quality for the film itself, and no pledge drive interruptions); The Fall of the House of Usher even has a restored “overture” section appended to the beginning of the film, spotlighting the score by composer Les Baxter. So this set brings me nothing but nostalgia. I wasn’t born when these films were released, but nonetheless I grew up on Vincent Price; films like The Pit and the Pendulum and Tales of Terror (1962) gave me nightmares, though Price’s self-mocking, over-the-top performances simultaneously reassured me that these were just movies. Thus, my parents didn’t mind my watching them, no matter how morbid they became. What a perfect match Price was for Edgar Allan Poe, then; Poe is still read in schools around Halloween, and teachers don’t seem to care if their students are warping their imaginations with the grotesque imagery of “The Black Cat” or “The Tell-Tale Heart” – because it’s literature, I suppose. I distinctly recall thinking, “I can’t believe they’re letting us read this.” I felt like I was getting away with something. You can see similar thoughts flicker through Vincent Price’s face, and his wicked smile.

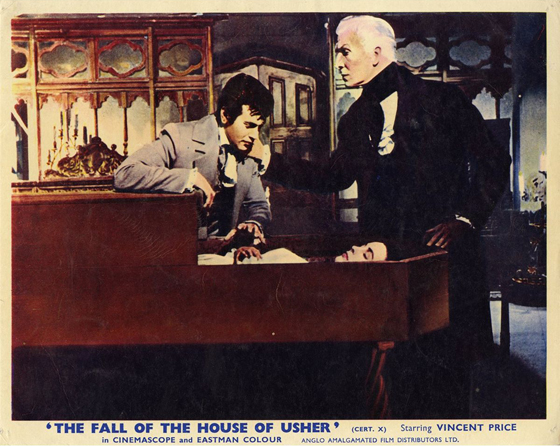

Lobby card depicting Philip Winthrop (Mark Damon) and Roderick Usher (Vincent Price) viewing the body of Usher's sister Madeline (Myrna Fahey).

Corman originally was asked by AIP to make two black-and-white films on the cheap, but in his 1990 autobiography (How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime), he states: “I said no. ‘What I’d really like to do,’ I told [James H. Nicholson and Sam Arkoff], ‘is one horror film in color, maybe even CinemaScope, double the budget to $200,000, and go to a three-week schedule. I’d like to do a classic, Poe’s ‘Fall of the House of Usher.’ Poe has a built-in audience. He’s read in every high school. One quality film in color is better than two cheap films in black-and-white.’ Jim wondered if the youth market was there for a film based on required reading in school. I said kids loved Poe. I had.” Poe must have seemed a natural choice. Across the pond, Hammer was at its peak, having revitalized three of the classic Universal monsters (Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula, and the Mummy) with Terence Fisher’s very British Gothics. To choose Poe was to go American Gothic. At the time, the only other writers so firmly associated with American nightmares were H.P. Lovecraft and Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Corman & Price would be getting to them shortly (with The Haunted Palace and Twice-Told Tales, respectively). So The Fall of the House of Usher is significantly a very American film, and its unequivocal success would launch a new series of American horror films, the face of which was Price.

Lobby card: Philip and Madeline journey to the catacombs beneath the Usher House.

With Corman in the director’s seat, he commissioned a screenplay from Richard Matheson, who had just begun writing scripts for Rod Serling’s new show, The Twilight Zone. Matheson had no easy task. Poe’s short story is low on incident, and what everyone really remembers about it is the ending. The tale could fill out an hour, but stretching it to eighty minutes is a tall order; Corman insisted that his film be long enough to be the main event, and not relegated to the bottom half of a double-bill below an inferior product. Matheson told writer Dick Lochte in 2005, “Everybody assumed I was an ardent fan of Edgar Allan Poe, which I wasn’t. But I tried very hard to catch the flavor of Poe’s story. I had to add a character, a suitor for the sister, or there would have been no story.” That character was Philip Winthrop, played by Mark Damon (Between Heaven and Hell), who brought the requisite matinee-idol good looks to the production, and, in the film’s second half, gets to practice some James Dean-style emoting; this very 1960 youth stands in for the narrator in Poe’s original, and doesn’t seem quite capable of the long, rambling soliloquies of the text. But never mind. Matheson does manage to add some dramatic tension, creating a bizarre love triangle with the lovestruck Philip trying to urge the beautiful young Madeline Usher (Myrna Fahey, Face of a Fugitive) to elope with him, while the possessive Roderick Usher (Price) insists she remain in the dilapidated Usher mansion, which is not only falling to pieces – a giant fissure runs up one side of the building, seeming to split it in half – but is also sinking into a swamp. Roderick has Madeline convinced that she is dying; and once the two of them are gone, the Usher legacy, with its history of corruption and vice, will finally be dissolved. They have a semi-incestuous bond which would probably be more effectively conveyed if the actors were closer in age. Further, Roderick radiates an obsessive madness, which seems to have infected not only his sister’s mind, but the very interior of the manor: as in the best of the Corman/Poe films, this landscape is one of nightmares. The exterior was shot, strategically, at the scorched location of a recent forest fire. The production design, by future director Daniel Haller (The Dunwich Horror), might be called Gothic-Psychedelic: all antique furnishings, bright colors, and slightly askew angles, as though everything is collapsing inward. Haller’s sets were built from stock sets purchased on the cheap from Universal, and they would be repurposed in subsequent Corman pictures to save on production costs.

One of the Usher clan portraits, by artist Burt Shonberg.

Even more psychedelic are the portraits which hang on the walls, surreal, macabre, and completely over-the-top. When Roderick indicates that these are his family portraits, you know it’s time to turn about and sprint out the door. The paintings are like those from Disney’s Haunted Mansion, if the characters were playing the Avalon Ballroom; one in particular, a female face exploding into rays as though she’s melting into a blood-red sun, reminds me of a famous portrait of Jimi Hendrix by Martin Sharp. These wonderful paintings are by Burt Shonberg (credited as Burt Schoenberg), a unique artist who harbored a fascination for the occult, and by 1960 was allowing his experiments with LSD to influence his work. Your heart may be in your throat when, in the film’s finale, the paintings are shown covered in flames; rest assured that Corman coated them with a fire-resistant gel, and they are now in the hands of collectors, Corman having distributed them to the cast and crew (including Price) once the filming was complete. The director wasn’t just plugged into the proto-psychedelia of Haller and Shonberg, but was fascinated by Freudian psychology, and intended his House of Usher to be the interior space of the subconscious. He noted in his autobiography, “For flashbacks and dream sequences in red and blue, I used either gel over the lights or a colored filter over the lens. We even blew in some fog.” These would all become important elements for the Corman/Price/Poe films, achieving their maximum effect in The Masque of the Red Death, though one could also say that Corman was setting the stage for his later hippiesploitation films like The Trip (1967) and Gas-s-s-s (1970). The matte paintings are also very effective, and the final shot, in which the house finally sinks into the bog, is nothing less than indelible, finally achieving a complete fusion with Poe’s fever-dream text (literally, since his words are overlaid upon the image). We may be watching the ground swallowing the Usher manor, but this single moment, more than any other, represents a cementing of the foundation for the popular and profitable horror series that would follow.

Madeline Usher escapes her sarcophagus.

But Price’s importance to that franchise can’t be undervalued. Sans mustache, Price’s Roderick Usher is one of his greatest roles: simultaneously loathsome, pathetic, and mysteriously haunted. There’s a moment in the film when Madeline is lying in her coffin with Roderick and Philip standing over her, mourning; Roderick notices movement in Madeline’s hands, and realizes she is still alive (she suffers from catalepsy, simulating death). Quickly he seals the coffin before Philip can notice. Why? Because this is his last chance to keep her; otherwise, he will lose her to Philip (and the modern world, and potentially a happy life). His action is despicable, but stems from his affliction of loneliness and self-pity. Matheson places this key moment to trigger the downfall that Poe described: Usher is destroyed by his own selfishness. Yet the real Price was nothing like the characters he’d become so famous for bringing to life. Matheson recalled in a 1994 interview for the New York Times, “Once, in playing a scene with Mark Damon…Damon comes looking for Roderick Usher carrying an ax. At the end of the speech, he swings the ax aside and quite by accident bounced it off Vincent’s shin. Well, Vincent let out a bellowing curse, walked around the entire set, and when he got back he was his old cheerful self again. And never again brought up the incident to Damon. He was a gentleman, a true gentleman.” Somehow this likability translated through the screen, no matter how evil a character he played. The audience liked to watch Vincent Price. For the next several years, as one horror film after another was delivered from the Corman/AIP factory, it was his charismatic presence that would keep audiences flocking to theaters. This shines through on the new box set, collecting some of his most iconic work.