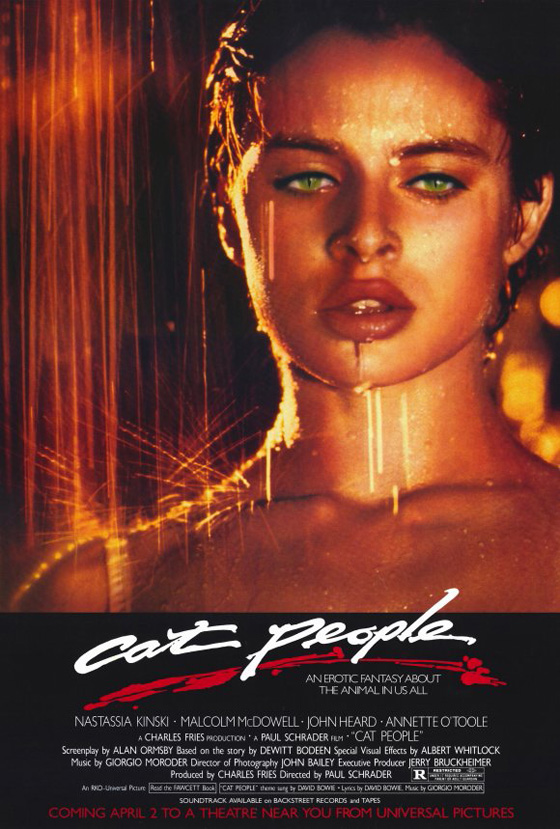

The early 80’s saw a flood of fantasy and horror pictures as New Hollywood directors, in answer to the studios’ demand for the next Star Wars (1977), paid homage to their childhood matinee memories with grittier, more effects-driven, and more adult visions of the fantastic. John Landis made An American Werewolf in London (1981) after old werewolf movies; John Carpenter remade The Thing (1982); John Milius channeled The Vikings (1958), Kwaidan (1964), and Japanese samurai movies with Conan the Barbarian (1982); and Paul Schrader, hot off American Gigolo (1980), used his new cachet to helm Cat People (1982), a remake of the 1942 Cat People from director Jacques Tourneur and producer Val Lewton. To call the original film a classic is an understatement: it is simply one of the finest horror films ever made, and the most iconic in the short-lived but highly-treasured series of noir-infused supernatural shockers that emerged from Lewton’s contract at RKO. Yet Tourneur’s picture is also, on the surface, a modest little B-picture, making the most of a slim RKO budget, and relying more on dialogue and suggestion than the monsters-on-the-rampage action of the Universal Studios horror films; with audiences it lacks the name recognition of a Frankenstein, Wolf Man, or Dracula vehicle, and it’s an unusual choice for a big-budget Universal remake. (The studio’s Psycho II, released the following year, was much more inevitable.) So it has the feel of a pet project for Schrader, much like Carpenter’s The Thing: a childhood favorite reimagined with an R rating. The irony wouldn’t be lost on critics. The Tourneur/Lewton film has sex on its mind, true, but, as with its supernatural elements, leaves it to the viewer’s imagination to fill in those empty spaces draped with black shadows. By contrast, Schrader leaves nothing unstated. Nothing is subtle. It’s a Paul Schrader film, and it’s the early 80’s: sex, blood, and style trump all.

Oliver (John Heard) prepares to tranquilize a deadly panther.

As with the original film, the plot concerns an immigrant named Irena (Nastassja Kinski, Tess, To the Devil a Daughter), a virgin who comes to believe that she’s from an ancient race of shapechangers, and sex will trigger her transformation into a deadly cat. This news is fed to her by her brother Paul (Malcolm McDowell, A Clockwork Orange), who welcomes her to New Orleans by telling her outright that he’s the only man with whom she can practice safe sex. Irena is much more interested in Oliver (John Heard, C.H.U.D.), who works at the New Orleans Zoo and is first seen climbing a ladder to tranquilize a panther on the rampage – who is really Paul in animal form. A mutual attraction leads Oliver to snagging Irena a job at the zoo’s gift shop. Their relationship only becomes more intense when a police raid on Paul’s apartment – human remains are discovered in a cage in his cellar – has Irena moving in with Oliver. Soon Irena finds herself anxious to unleash her inner beast. It should be noted that in the original film, the story never threatens to become a pro-abstinence parable: Lewton and Tourneur are more interested in Irena’s isolation, loneliness, jealousy, and resentment, as her unwillingness to consummate her marriage leads her husband to take a greater interest in Alice, a more vivacious co-worker. (A recurring theme in Lewton’s films are isolation and suicidal misery.) But the key difference with Schrader’s Cat People is that Kinski’s Irena wants sex. As Paul tells her, she’s not in love with Oliver: it’s simply lust. (There is no talk of marriage in this film, either.) In the more liberated 80’s, a woman has the right to enjoy her sexuality. Late in the film, she gives Oliver a choice: kill her or let her be free. Oliver compromises in a kinky way. He ties her to the bed so they can have sex with minimal risk of injury. This is reinforced in the film’s final image, which shows us an Irena who is “free” in only one sense of the word – she is still essentially confined, even if she can finally be herself.

Irena witnesses an attack at the zoo.

Lest anyone think Schrader is desecrating a classic, there are plenty of loving references. RKO Pictures gets a shout-out in the opening titles, and Schrader ensures that the most famous scenes of the original are all here, albeit in altered shapes. The zoo (a studio set) bears a close resemblance to the original’s; a mysterious woman (Neva Gage) approaches Irena in a bar to identify her as a fellow cat (“Mi hermana!”) before abruptly leaving the film; the notorious stalking of Alice through dark streets in the original film, in which a screeching bus suddenly appears just when we expect a pouncing cat, is reproduced here in a park in daylight, though our Alice (Annette O’Toole, 48 Hrs.) is startled by both a bus and an aggressively affectionate Great Dane. And the trapped-in-a-swimming-pool scene is replicated almost shot for shot, with the key difference that O’Toole is topless for the duration. This, along with the kinky sex – incestuous overtures and bondage – would lead many to accuse the film of being a very cynical remake. When I first saw the film, I found it a bit dull, and its sexual bluntness peculiar and bordering on camp. But a reassessment courtesy Shout! Factory’s recent Blu-Ray release reveals the film as one of the sturdier in the early-80’s run of slick, adult fantasy films. It is camp, and I think deliberately so, but it works because it’s played with sincerity by the cast. McDowell doesn’t chew the scenery quite as much as he probably would today, but he nonetheless makes the most of a character defined by his lust for eating people and seducing his virginal sister: in one scene he hops cat-like onto the edge of his sister’s bed and gazes at her with giant, hungry eyes; in another, he guides Irena through an orange-hued desert to a tree whose boughs are laden with panthers, telling her, “Before we become human again, we must kill.” Even Ed Begley Jr. (This is Spinal Tap) plays it straight as a zoo worker who gets his arm ripped off with gallons of gushing blood – which splatter symbolically across Irena’s white shoes. (Schrader isn’t content with the relative subtlety of symbols. Later, when Irena loses her virginity, she rubs the blood of her broken hymen across her lips.)

Irena (Nastassja Kinski) prepares to repel an incestuous advance by her brother Paul.

Decades later, the original Cat People is still widely available and remains an untouched classic, so it’s easier to safely regard Schrader’s interpretation as something separate, alternate: a Paul Schrader film. And in that regard it’s one of his key works, playing explicitly with his central obsession of sexual repression. Yet the film almost resists analysis because, as I’ve said, it contains no subtext. It’s all right there in the dialogue and images, everything explicit. Like an 80’s music video – and so many of its cinematic contemporaries – it’s a film of style, the work of a sensualist in love with the power of images and music. The synthesizer-driven score is by musician Giorgio Moroder, who had scored Schrader’s American Gigolo and would go on to create the 80’s-rock cut of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1984). David Bowie moans over the opening credits, constantly threatening to burst into song, which doesn’t occur until the final credits (a part of the repression theme, perhaps): the rather awesome “Cat People (Putting Out Fire)” would later be reappropriated in Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds (2009), which has no cat people in it. I still find Schrader’s film slow-moving (it’s too long) and rather redundant, which is the problem with having the characters speaking directly about what is already clear in the images. But here is Nastassja Kinski, with her absurdly sensual lips and gigantic eyes – and, when she strips off her clothes, a lean, sinewy body – the most perfectly cast feline female this side of Simone Simon. I’ve come around a bit on this film. Schrader’s Cat People is absurd, over-the-top, and utterly silly, but it’s also unique, eccentric, and as restless as a cat in heat.