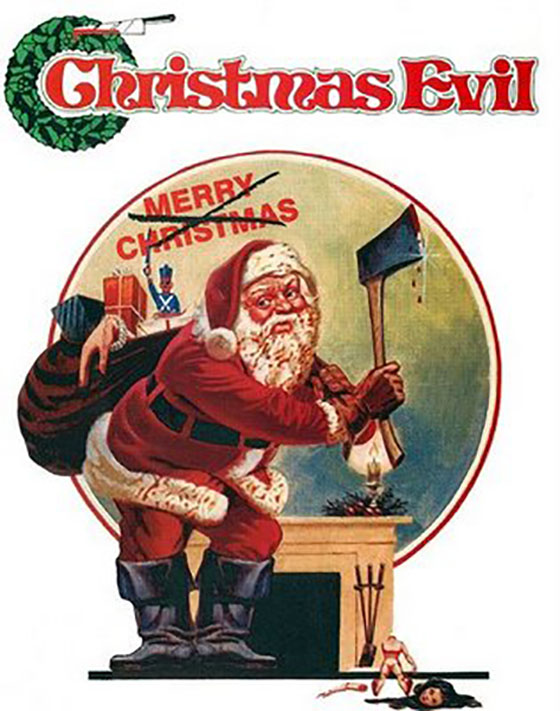

Multiple versions of “Santa Claus is Coming to Town” play prominently throughout Christmas Evil (1980), including a disco cover, but frequently it’s just deranged Harry Stadling (Brandon Maggart, Dressed to Kill) humming it to himself while he implodes, and then plots, and finally murders. Over and over we hear “You better watch out…” – which in fact was the original title of this black comedy from writer/director Lewis Jackson (The Transformation: A Sandwich of Nightmares). If only those around poor Harry had watched out, and treated him better, he wouldn’t have snapped, donned a Santa Claus outfit, and begun offing those who wronged him. Indeed, he makes a list and checks it twice, finding out who’s naughty and nice by standing on a rooftop with a pair of binoculars, spying on children through their bedroom windows – though anyone who might catch him in the act wouldn’t realize his true intentions. He returns to his home, decked out in wall-to-wall Christmas decorations and paintings of Santa Claus, and opens two massive tomes: “The Good Boys & Girls Book” and “The Bad Boys & Girls Book.” When he sees one boy reading Penthouse magazine, “indecent thoughts” is added to the list which also includes “pulled Sally’s hair,” “picks his nose,” “kicks over garbage cans,” and “gets up late every day.” As he later tells a group of delighted children, “Respect your mothers and fathers and do what they tell you. Obey your teachers and learn a whole lot. Now if you do this, I’ll make sure you get good presents from me every year. But if you’re bad boys and girls, your name goes in the ‘Bad Boys & Girls’ book, and I’ll bring you something – horrible.”

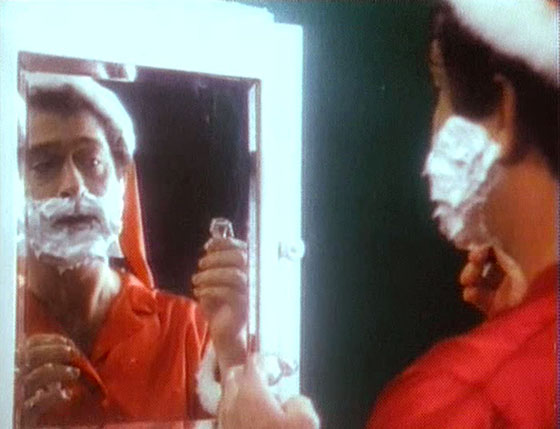

Harry (Brandon Maggart) begins his typical day.

Harry’s day job is at the Jolly Dreams toy factory (an assembly line actually owned by the Pressman Toy Corporation; the film was produced by Edward R. Pressman), located in a dreary factory district, where he deals with depressing workplace politics and misbehavior, including working an extra shift for Frank (Joe Jamrog) who calls in sick, but whom Harry later sees laughing it up at a bar. He also learns that the company isn’t fully committed to donating free toys to a local children’s hospital. Ostracized by his co-workers and increasingly isolated and delirious, Harry finally snaps as Christmas approaches. He descends to his basement workshop and begins creating new toys, including toy soldiers with razor-sharp bayonets. He raids the factory and delivers toys to the children’s hospital to the delight of the nurses. He learns how to bellow “Merry Christmas!” in a convincingly Santa-like manner (this takes some practice, however). And when he feels that some churchgoers are behaving disrespectfully toward him, he slaughters them with one of his toy soldiers and a hatchet right on the church steps. The suspect is simply described by witnesses as a man in a Santa costume, so Santas are corralled into the police station for a line-up. But if you’re a good boy, you’re safe from harm. Harry takes the time to join a Christmas party in a tavern, dancing merrily. He delivers presents to a family only after an aborted attempt to climb down a chimney, which is narrower than he’d planned. And when two children spy on him placing presents under their tree in a very “Night Before Christmas” scene, he’s satisfied, fulfilled; after he sees they’ve slipped back to bed, he tiptoes off to murder their father, that Frank who lied when he called in sick. He tries to smother him with his bag of toys, but resorts to slicing his throat with a Christmas ornament.

Harry uses his sack of presents to smother one of his co-workers while he sleeps.

This behavior is rather inadequately explained by a surreal prologue in which young Harry spies upon his father, disguised in Santa costume, pawing at his mother’s thighs and silk panties. How can Santa be naughty? As a grown-up, his Santa obsession has become all-encompassing, so that the slightest nudge pushes him into the delusion that he must become a Saint Nick of deadly retribution. A superficially similar plot propelled the later Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984), but this film, set in a grubby everyday world of factory work, late-night drinking while the Phil Spector Christmas Album plays its hits, and occasional sex (well, not for lonely Harry), is really about midlife crisis. The slasher elements are actually minimized. As Jackson stated in a 2012 interview with Nitehawk Cinema, “I actually got the film made because of the success of Halloween. And I let the misconception stand to get the money…I hate slasher movies. Killing girls who have sex was a very Reaganesque idea that still seems to play with evangelicals.” There really aren’t very many slasher clichés in Christmas Evil. Instead, the film’s drab visual aesthetic begins to dissolve into something more surreal and exaggerated. A torch-bearing mob chases Harry through the streets. And when he drives his sleigh (a van with a sleigh painted on the side) over the edge of a bridge, it miraculously begins to fly. The narrator, absent since the prologue, concludes: “And I heard him exclaim as he drove out of sight, ‘Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!'” Finally, a jazz version of “Jingle Bells” plays over the end credits. John Waters calls this “the greatest Christmas movie ever made.”