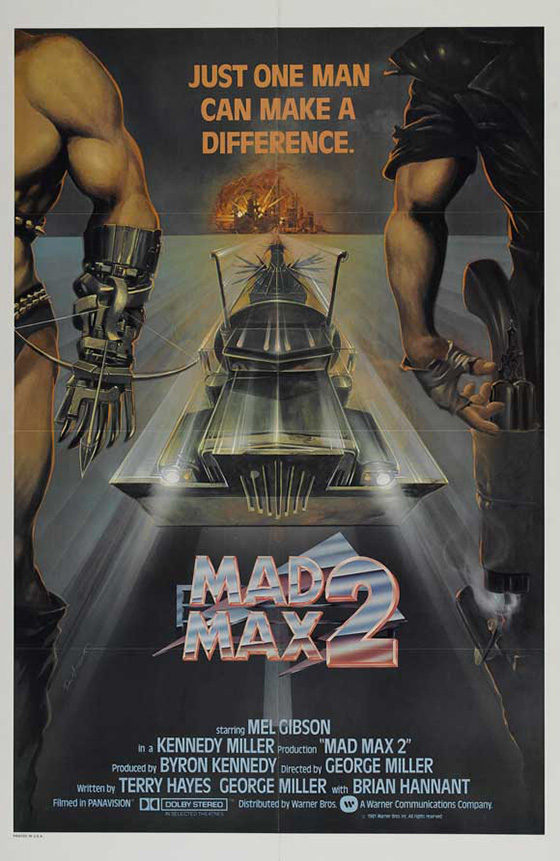

Two years after the benchmark Ozploitation film Mad Max (1979), director George Miller returned to the world of violent punks and souped-up cars with Mad Max 2 (1981). The film was cautiously retitled The Road Warrior for the U.S., because the majority of American moviegoers had never heard of the first film, barely released in the States. Of course, knowledge of Mad Max is inessential to enjoying Mad Max 2, for Miller had by now pared down story to only its crudest parts, and revved up his technique. Mad Max is a dark revenge saga about the last remnants of law and order falling to pieces in a post-apocalyptic Australia. Mad Max 2 tips the scale in favor of black humor and breathless action. This is a film which approaches the definition of “pure cinema.” With dialogue kept to a minimum (notably, one of the main characters communicates entirely in grunts), and the plot as spare as possible, Miller relies upon heart-stopping stunt sequences and an impeccable mise-en-scène – every frame of this film is perfectly composed, packing in all the story and character you need as events propel forward. There’s an ex-cop named Max (Mel Gibson). He has a dog, and they eat from the same can of dog food while wandering the Outback and stealing precious gasoline to keep his V-8-powered “Pursuit Special” running. He finds another scavenger (Bruce Spence, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King), who will be credited only as The Gyro Captain because he flies a gyro. He guides Max to a walled enclave in the desert: an oil refinery under siege by marauders led by a masked muscleman called Humungus (Kjell Nilsson). When Max witnesses a man from the refinery beaten by the gang, his female companion raped and killed, Max delivers him back to the compound only to watch him die at the threshold. Max strikes a bargain with the besieged community: if he brings them a truck so they can escape the refinery with barrels of fuel, he’ll be rewarded with all the gasoline he needs to keep surviving. But his mercenary sensibilities gradually soften, and finally Max agrees to lead the charge across the desert, Humungus and his men pursuing them in a dusty, high-octane chase.

Humungus and his gang approach the walled oil refinery with hostages.

Mad Max 2 is so successful in its simple combination of elements that it has come to define the term “post-apocalyptic wasteland.” So evocative is its landscape that endless B-movies, books, comics, and video games have been spawned to fill it: all of which must somehow contain leather, desert, mohawks, and wheels. Very few of these actually bear the Mad Max license (though I do have scars from a particularly awful Mad Max Nintendo game). Miller has kept a firm grip on his idiosyncratic franchise, completing a trilogy with Mel Gibson (1985’s Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome), then taking an extended hiatus with The Witches of Eastwick (1987) and Lorenzo’s Oil (1992), as well as the lauded children’s films Babe: Pig in the City (1998) and Happy Feet (2006). Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), with Tom Hardy as Max, is Miller’s long-awaited return to his roots. But what strikes me in revisiting Mad Max 2 is just how deliberately eccentric Miller’s vision of the future was. Growing up, these films (like anything with Gibson) were the epitome of tough and cool. Watching it with my wife last night, she asked the legitimate question, “So in the future all that’s left is assless pants?” Miller makes a point of having the villains be as silly as they are scary. He keeps hold on the menace from the first film, but only just. A brief rape scene, glimpsed through the remove of a spyglass, tastelessly bumps shoulders with borderline slapstick gags. It’s not enough that the villains are punks drenched in sweat and hairspray; Miller gives us an intentionally funny shot of Humungus’ henchman being carefully groomed. The fetish gear is impractical and over-the-top. As for Humungus himself, he’s introduced like a rock star, speaking into a microphone after his own emcee introduces him. He’s not just muscle; glimpsed from behind, we can see that his head throbs and pulsates, a radiated mutant. Most of these outré elements shouldn’t work, but they do in the context of exploitation film, playing to the cheap seats seeking escalating bits of outrageousness. (While rewatching this film, one name kept springing to mind: Sam Raimi.) But Miller handles it all with wit, and characters so cartoonish that Max, tragically defined but also the audience surrogate, stands out in sharp relief. It’s the world that’s mad, not Max.

Max (Mel Gibson) and his dog.

Miller is always in complete control of the craziness. Watch the scene in which the Gyro Captain boasts about his vehicle to awestruck onlookers while the Feral Kid (Emil Minty) persistently ignores his warning to not touch it: the camera, like the Gyro Captain, tries to stay focused on the speech while being distracted again and again by the Feral Kid, until the Kid finally bears his teeth and growls. It’s comic, but it also gives us everything we need to know about these two characters. Or even smaller bits of business like the forced smile of the Toadie (Max Phipps) after his fingers have been cut off by the Feral Kid’s boomerang: nothing should interrupt the ceremony he’s given his boss, Humungus. Or the wonderful scene in which a mechanic’s diagnosis of the disabled Mack truck is laboriously repeated by his squinting assistant at top volume. Or just the way that Max’s dog is a perfect reflection of Max, forever stalking beside him, snapping his jaws so Max doesn’t need to. To help translate this bizarre landscape, Miller uses the narrative language of Westerns, in particular John Wayne movies: the oil refinery becomes The Alamo (1960), and the high-speed flight echoes Stagecoach (1939), with motorcycle punks instead of Indians on all sides. That climactic chase, Miller’s attempt to one-up the impressive stunts of Mad Max, is one of the greatest action sequences in cinema. While a badly-bruised Max struggles to keep hold of the wheel, the marauders speed alongside his truck, climb over and around it, and get crushed beneath it, all while the gyro sputters along overhead. But even the chase doesn’t overstay its welcome. Mad Max 2 is lean, mean, and carries only as much as it needs.