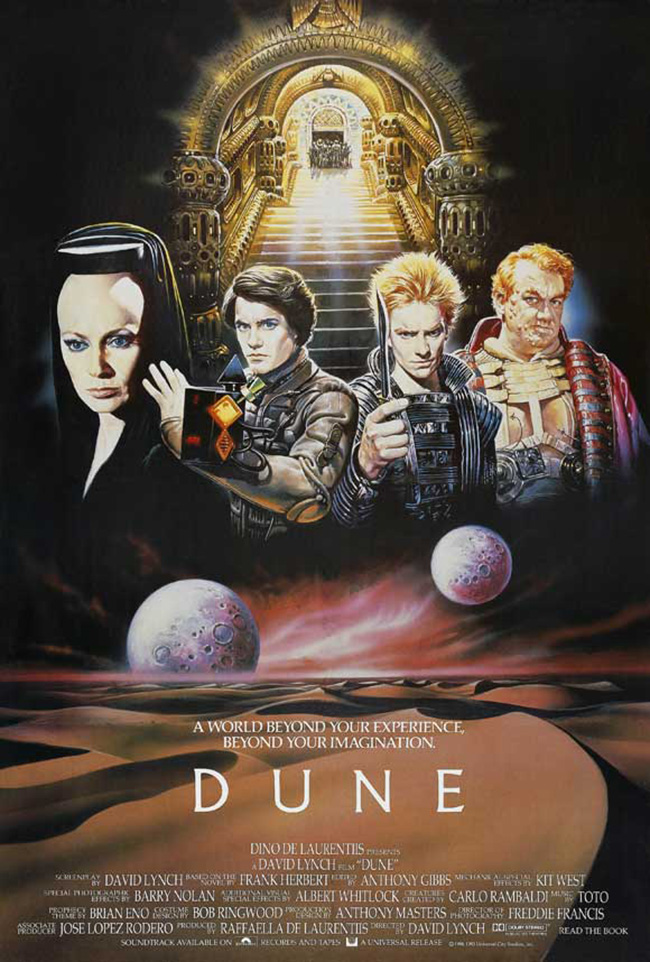

It’s the 50th anniversary of Frank Herbert’s Dune, the science fiction novel which broadened the scope and ambition of the space opera. Herbert’s novel nudged the genre into new degrees of sophistication with its dense plotting, elaborate backstory, wide cast of characters, and dialogue which often requires the book’s lengthy glossary to decipher. Winner of the Hugo and Nebula award, it spawned five bestselling sequels by Herbert’s hand, and additional volumes from his son Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson. Its influence can be felt in Game of Thrones, which also contains a huge cast and a storyline driven by warring houses, betrayals, and shocking deaths. But it’s undoubtedly an intimidating work. Dune takes its time building momentum; much like being transported for the first time to the desert planet, a period of acclimation is required on the reader’s part. Herbert’s third-person omniscient approach can also be awkward, if not disorienting, and the book is not without its clumsy moments. Where it rewards is in the depth of its ideas: precognition, greed, ecology, prophecy, mind-expanding drugs, and jihad are all at play. Since its publication, it has won a devoted following, and many have sought to bring it to the big screen. The superb documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune (2014) delves into the Dune that might have been, when, in the mid-70’s, writer/director Alejandro Jodorowsky (El Topo, The Holy Mountain) and producer Michel Seydoux (Prospero’s Books) tried to launch an adaptation with an incredible assemblage of talents: Dan O’Bannon, Moebius, H.R. Giger, Pink Floyd, Salvador Dalí, Orson Welles, and more. Despite Jodorowsky’s visionary approach, he couldn’t convince a studio to finance the project. The rights were sold to Dino DeLaurentiis, who, as Seydoux tells it, presented them as a gift to his daughter Rafaella. Ridley Scott, hot off Alien (1979) – which, ironically, used some of Jodorowsky’s dream team – was engaged to direct the film, from a screenplay by Rudolph Wurlitzer (Two Lane Blacktop). When he dropped out of the project for personal reasons, Dino and Rafaella went to David Lynch, whose profile had spiked following his sensitive work on The Elephant Man (1980). That film was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Director – quite an achievement for a man whose only other credit was the disturbing midnight movie Eraserhead (1977). But despite the years of planning, and the expectation that the film would be the new Star Wars, the resulting Dune (1984) was a failure with critics, audiences, and many of the book’s fans. In 2000 the Sci Fi Channel premiered the miniseries Frank Herbert’s Dune (2000), which was more warmly received, enough to warrant a sequel. But fans remain obsessed with the idea of a perfect Dune adaptation, like the blue-eyed, spice-breathing Fremen of Arrakis, awaiting the coming of their messiah.

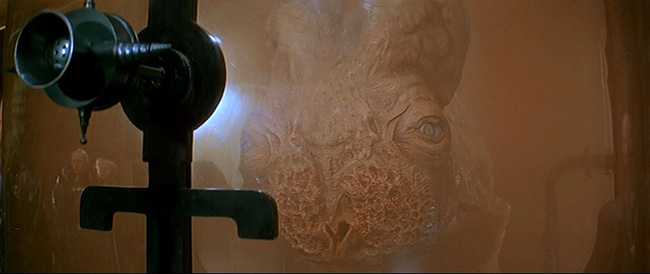

A spice-altered Guild Navigator, as imagined by David Lynch.

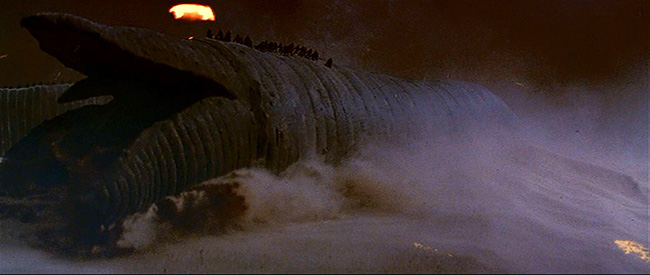

Even if it’s generally agreed that Lynch’s film is not that messiah, it can at least be said that the film is faithful. To a fault, it is faithful. The House Atreides – Duke Leto (Jürgen Prochnow, Das Boot), his concubine Lady Jessica (Francesca Annis, Macbeth), and their son Paul (Kyle MacLachlan, in his debut) – are given stewardship of the desert planet Arrakis, aka Dune. This is part of an elaborate scheme hatched by their rival, the planet’s former ruler, Baron Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan, Salem’s Lot). He’s blackmailing the Atreides doctor, Yueh (Dean Stockwell, The Dunwich Horror), to betray Leto once they’re on Arrakis, at which point Harkonnen will invade and permanently wipe out the Atreides line. Despite the fact that Arrakis is covered entirely in sand and rock, it’s of utmost strategic importance because it provides melange – spice – which is necessary for interstellar space travel. Guild navigators use spice to “fold space,” and are subjected to radical mutations as a result. Exposure to spice also allows one to see the future, or at least different paths of the future. As the Baron prepares for his strike against the House Atreides, young Paul enhances his mind and voice with the powers of the Bene Gesserit, a feminine school of which his mother is a part; and he learns advanced combat techniques from the warrior-bard Gurney Halleck (Patrick Stewart, only three years away from Captain Picard). When Harkonnen invades, he and his mother, pregnant with Leto’s daughter, flee into the southern deserts of Arrakis, where they join up with a tribe called the Fremen, their eyes turned blue from frequent proximity to spice. They have long prophesied that a boy and his mother would teach them new ways of combat and lead them to liberate Arrakis, and so Paul settles among them, falling in love with one of their warriors (Sean Young, Blade Runner), and learning to ride massive sand worms.

Baron Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan) gloats over the dying Duke Leto (Jürgen Prochnow).

Lynch originally turned in a cut that was about three hours long. The theatrical release was whittled down to a still-very-bloated 137 minutes. Even in this shorter version, it feels like the entire novel is on the screen, which is exactly what Dino and Rafaella DeLaurentiis wanted. No character has been excised – everyone will at least get a cameo. It is hard to justify the presence of Paul’s friend Duncan Idaho (Richard Jordan, Logan’s Run), or Fremen housekeeper Shadout Mapes (Linda Hunt, The Year of Living Dangerously), or even Harkonnen’s nephew Rabban (Paul L. Smith, Popeye), except that they are in the novel, so they must be here. Sure, Rabban is given Arrakis to rule, a puppet of the Baron Harkonnen – but I would be impressed if a viewer unfamiliar with the book ever picked up on that detail. Is it necessary to include Jessica’s pregnancy and the birth of her daughter Alia (Alicia Witt)? Alia receives one scene in the film, and although it’s a crucial one, the task she performs could easily have been handed to another character. Nowhere is there the art of compression, of excision, of editing Herbert’s lengthy book. By committing to tell the whole thing, Lynch’s Dune backs itself into a corner. Now it must explain everything. This means that the film takes forever to get going, with endless exposition, sometimes repeated in whispered thoughts – Lynch’s attempt to recreate Herbert’s prose style. A last-minute addition to the theatrical cut provides a narrator, the Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen, Candyman). But this only layers more exposition and more redundancy. To summarize, Dune is a movie that never stops talking at you, repeats itself often, and is still indecipherable if you don’t have the novel in hand.

A very young Alicia Witt as Paul’s sister, Alia.

At least it’s a handsome film. The sets in Dune are really something, picking up where Dino and Rafaella left off with Conan the Barbarian (1982), another genre film given the first class treatment. The abode of the Emperor (José Ferrer, Lawrence of Arabia) and the corridors and chambers of the palace on Arrakis are intricately designed, the homeworld of the Harkonnens imaginatively realized (with a certain Giger influence carried over from the first, aborted attempt at Dune). The colossal sand worms are great to look at, though it seems a waste that a film which takes place on a desert planet has so few sequences actually filmed in a desert. Perhaps because there are so many dialogue scenes to cram into the running time, Dune is more set-bound, more claustrophobic than it ought to be. And despite the impressive Guild Navigator prop, which looks like a giant floating cow fetus, the effects in Dune are often not that special. In the golden age of Spielberg, Star Wars, and Blade Runner, audiences had a right to expect dazzling effects from a science fiction spectacle. Dune has too much blue screen and some pretty clunky opticals. One gets the feeling that Lynch’s heart just wasn’t in it (despite his amusing cameo appearance as a spice harvester barking into a microphone with that distinctive David Lynch voice). Science fiction wasn’t his bag. He does, however, perk up during the story’s opportunities for the grotesque. When Paul is having visions of the past and future, Lynch shows us the mutant Guild Navigator, and zooms in on his vagina-like mouth, billowing plumes of red spice. To illustrate that Jessica’s unborn daughter is being altered by exposure to the Fremen’s Water of Life, his camera dives straight into her womb, where the transforming offspring resembles something from Eraserhead. As with that film and The Elephant Man, Lynch continues his fascination with physical deformity, giving us a fat but levitating Baron Harkonnen covered with oozing sores and subjected to operations by surgeons who look like Hellraiser’s Cenobites. There are even his trademark camera dollies into mysterious black portals, one of which is a tear on Duke Leto’s face following the explosion of a poison gas-filled tooth. (Freddie Francis, cinematographer on The Elephant Man, collaborated again with Lynch on Dune.) But Lynch is compromised here. The budget is so large that he can’t be granted full control; there’s too much at stake for what Universal hoped would be their new Star Wars franchise.

The Fremen ride sand worms in the climactic siege.

Perhaps because Lynch did not have final cut, it’s lacking the rich sonic texture of his other films. Lynch likes to orchestrate a dense and disturbing sound design. Dune, by contrast, has a soundtrack dominated by Toto. Toto – the band that blessed the rains down in Africa, gonna take the time to do some things they never had, etc. Continuing the 80’s pop theme, Sting plays the key role of Feyd Rautha, oiled up in a loincloth and lusted after by Harkonnen, and given the climactic knife-duel with Kyle MacLachlan. I would comment upon Sting’s casting, but, like everyone else, he’s not given much to do, lost in the sandstorm that is Lynch’s Dune. In the 80’s, an extended version of the film was aired on television, subsequently released on DVD. Lynch had his name replaced with “Alan Smithee” for this cut of the film. In revisiting Dune for the third time in my life, I introduced myself to this cut for variety’s sake. The Princess Irulan is replaced by a different narrator, who now turns the exposition game into a sadistic sport: characters stand on the screen, smiling patiently while the narrator explains who they are. The new footage fills out most of the remaining corners of Herbert’s book (including some concept paintings which describe the pre-history of this world, in which humans were enslaved by computers), but none of this helps the film. After subjecting myself to all three hours of the Alan Smithee cut, I returned to the Lynch version and rewatched the first half hour and select portions of the film. Don’t be alarmed – a day-long break was involved. But the theatrical version still left me frustrated, and, frankly, I don’t believe any cut could turn it into a good movie. The performances are still wildly disparate: the great Brad Dourif, for example, appears to be acting in his own separate Dune (one that I’d probably rather watch). As for everyone else, they appear to be lost in a kind of dead zone, a set, an atmosphere, that is robbing the enthusiasm from them. (Someone get their quota of spice, stat.) People continue to pester Lynch about Dune, asking if he’d be willing to do a new cut, and he shrugs them off. I understand that. He did Blue Velvet (1986) next; that’s all you need to know. Perhaps the best Dune would be a TV series, Game of Thrones style, giving viewers the opportunity to learn the language of Frank Herbert and Arrakis and taking more time with the story and characters. But whoever accepts that mantle next, it’s important to tear apart Dune and make it into something new – something that fits its medium. If we’re slaves to the idea of the “faithful adaptation,” we may never get the best Dune of all.