For years, pin-up photographer-turned-independent filmmaker Russ Meyer wanted to work in Hollywood. His invite came after the surprising box office success of his X-rated Vixen! (1968), and at the moment when Hollywood had pretty much thrown up its hands and said “I don’t know what you people want anymore.” Twentieth Century Fox handed Meyer the keys to a Valley of the Dolls sequel, Meyer hired Roger Ebert to write the script, and the result was the delirious Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), critically panned, financially successful, and one of the most entertaining movies of the 70’s. Meyer made one more in the studio system, the courtroom drama The Seven Minutes (1971), which allowed him to opine on the subject of censorship. Then it was back to the wilderness of independent filmmaking. After the poor reception for Black Snake (1973), his take on blaxploitation, Meyer decided to return to the kind of movie that had made him successful in the 60’s, and which had stirred his creative juices: camp comedies starring his favorite large-breasted strippers and go-go girls. Supervixens (1975) kicked off a trilogy – followed by Up! (1976) and Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens (1979) – of self-referential Meyer films. They cashed in on his image as a burlesque showman – “Come one, come all, come see the women with the most perfect breasts in the world!” – while also offering an extended journey through his imagination, his Id, his worldview, all of which are unique, to say the least. On top of this, like a layer of frosting so rich you can’t finish the cake, the films send up Russ Meyer movies. It’s enough to turn your head inside-out, and much of it is fueled by Meyer’s pride in that prism of satire and self-satire, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, which he considered his finest work. No wonder that Ebert was brought back to help write Up! and Ultra-Vixens. But of this career-capping trilogy, Supervixens is the best. It is a summation of everything Russ Meyer, and it is utterly mad.

Shari Eubank as SuperAngel.

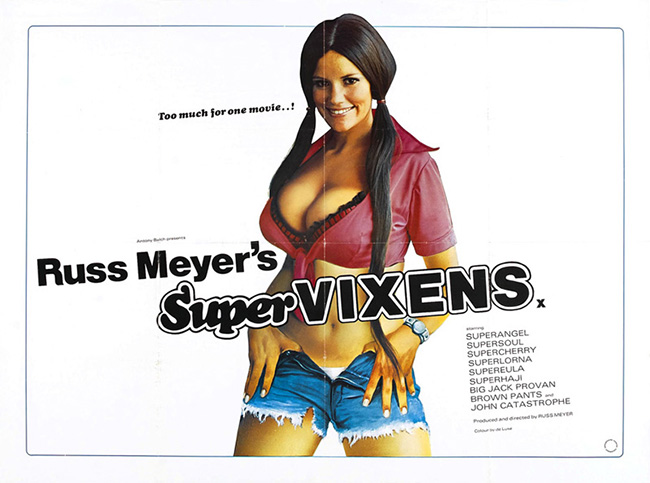

Supervixens provides one inside joke after another, winks and nods to fans of his work. It is a film that requires footnotes, or perhaps breastnotes. It’s also unique for stretching Meyer’s comic-book style to accommodate one showstopping moment of downbeat, graphic, and very grindhouse violence – this, in the middle of a burlesque comedy. In the 70’s, the landscape had changed, and the commercial market for exploitation was more competitive. Drive-ins and seedy theaters were screening all sorts of taboo-busting films: his “discovery” from Cherry, Harry, & Raquel (1969), Uschi Digard, appeared in quite a few of them, including the Nazisploitation Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS (1975). Hardcore pornography was in fashion and more easily accessible than when Meyer first started. But Meyer wasn’t interested in shooting hardcore sex; he was contemptuous of its artlessness. He wanted brassy, big-breasted women, and energetic editing, not lingering shots of copulation. His idea of adapting to the times was inserting a couple of brief, hilarious shots of his male actors sporting very long and obviously fake penises. (In Meyer’s world, all the “studs” are well hung.) His solution to remaining commercial successful was overstuffing his film with beautiful women and episodic digressions, even wildly varying tones and attitudes. Supervixens would have everything. The poster boasted, “Too much for one movie!”

Charles Napier as sadistic cop Harry Sledge.

The film seems to be organized into three acts. In the first, gas station attendant Clint Ramsey (Charles Pitts, The Girl Most Likely To…) tries to work his day job while his sexually insatiable girlfriend SuperAngel (Shari Eubank) pesters him on the phone. He works at Martin Bormann Super Service, because Meyer’s films often feature a Nazi named Martin Bormann, for no particular reason except it amused the director, a WWII vet. (Bormann here is played by Henry Rowland, who would reprise the role in Ultra-Vixens, and played a Bormann figure in Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.) When a pigtailed girl named SuperLorna (Christy Hartburg), named after Meyer’s Lorna (1964), teases Clint with some go-go dancing, SuperAngel goes ballistic, and so he must rush home to satisfy her. Their relationship is a tumultuous one, and after sex they get in a dust-up outside his house. She attacks his truck with an axe, screaming “I wanted a Cadillac!” SuperAngel is hurt in the ensuing wrestling match, and the neighbor calls the cops. Arriving at the scene is the chilling Harry Sledge, played by Cherry, Harry & Raquel‘s Charles Napier. Napier is one of the few actors in Meyer’s repertory to move on to a rich acting career; IMDB lists 201 credits, including appearances in Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985), Philadelphia (1993), and Austin Powers (1997). He also served as executive producer of Supervixens, and Harry Sledge is one of his most memorable performances. Napier’s unique look fit Meyer’s ideal of the “square jawed” stud, but he cocks a wicked, dangerous smile in Supervixens. When he takes SuperAngel back from the hospital and fails to sexually perform, she begins hurling insults, leading to a brutal confrontation. She locks herself in the bathroom, and the enraged Harry begins stabbing the door with a knife. Finally he knocks the door down, and the knife, still stuck in the door, pierces her as she’s trapped underneath. He throws her in the bathtub and stomps her until the water turns red. SuperAngel is still alive – barely – when he drops a radio in the water, electrocuting her. At this point you may well ask what the hell you’re watching. But according to Napier, quoted in Jimmy McDonough’s Meyer bio Big Bosoms and Square Jaws (2005), Alfred Hitchcock loved the scene, and had Napier signed to Universal.

Clint Ramsey (Charles Pitts) accepts a ride from the perverse couple SuperCherry (Sharon Kelly) and Cal (John Lazar).

In Act II, Clint, accused of SuperAngel’s murder, goes on the run, hitchhiking across the Sonoran Desert. He’s picked up by SuperCherry (Sharon Kelly aka Colleen Brennan, Foxy Brown) and her guy Cal (John Lazar, “Z-Man” from Beyond the Valley of the Dolls), but resists their overture for a menage à trois. When Cal is bitten by a snake, he demands that SuperCherry suck it out, and she spits the milky venom at the camera – a blowjob joke that originated in Meyer’s Motorpsycho (1965). After they rob Cal and leave him beaten by the side of the road, he’s rescued by a kindly farmer (Stuart Lancaster of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!) who happens to be married to an Austrian mail-order bride (Uschi Digard), introduced suggestively milking a cow in a cleavage-spilling milkmaid’s outfit. The character is called SuperSoul, after Digard’s character in Cherry, Harry & Raquel. One of the many unexpected sights of Supervixens is the elderly Lancaster having acrobatic sex with his mail-order bride all over the farm while Clint tries to do his chores. The typical farmer’s wife/daughter humor ensues as SuperSoul can’t keep her hands off Clint, and the joke or more or less repeats when Clint becomes reluctantly involved with a motel owner’s mute daughter, SuperEula (Deborah McGuire). For a stretch the brutal murder of SuperAngel feels like it happened in some other movie. We’re in Benny Hill territory now.

SuperSoul (Uschi Digard) milks the cow.

But SuperAngel returns in Act III, reincarnated in a pillar of fire atop a desert mountain. She is now SuperVixen (Shari Eubank again), working at “Super Vixen’s Oasis” as a gas station attendant – Clint’s old job. Wearing white rather than her original black nightie, her personality has flipped to tender and loving. Clint falls in love and helps her out at the gas station, but interrupting their idyll is Harry, who recognizes the couple and begins to plot their downfall. All this leads to a desert showdown similar to Motorpsycho and Faster, Pussycat, with Harry tossing dynamite at Clint with a slingshot, and SuperVixen tied to stakes in the ground. We’re in a Dudley Do-Right cartoon. SuperVixen screams “Leapin’ Lizards!” like Little Orphan Annie. The villain is vanquished, but this is about as strange as crowd-pleasing entertainment comes. The circular nature of the plot – SuperVixen unconsciously repeats to Harry some of SuperAngel’s dialogue from the beginning of the film – lends a dream-like quality to the film too, which makes it perfect for late-night viewing. Over the subsequent films in the trilogy, Meyer’s narrow worldview would come across as increasingly bizarre, almost suffocating (Ultra-Vixens has yet to win me over, but I’m willing to give it another shot). But Supervixens has its pleasures, not the least the feeling of an artist liberated from the needs to please anyone but himself and his devoted fans. He edits like mad (no shot lasts more than a few seconds), and he frames his vixens and studs like Lichtenstein. As he intended, there was nothing at the grindhouse doing anything remotely similar.