Jacques Demy was one of the most important directors of the French New Wave, but his films seem to sit far apart from those of Godard and Truffaut. After working with composer Michel Legrand on the dramas Lola (1961) and Bay of Angels (1963), the two began a rich collaboration reinventing the movie musical. (Lola featured a brief, memorable musical number sung by Anouk Aimée, but otherwise Demy’s first two films had the feel of musicals that never quite got around to the singing.) In the colorful but melancholy The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), all the dialogue is sung. Star Catherine Deneuve became a sensation, and Legrand’s soundtrack was a hit in record stores. The follow-up, The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), united Deneuve with her sister Françoise Dorléac – as well as Gene Kelly – in a tribute to Hollywood musicals. Although the film has become a classic, Demy worried he’d lost something in his rush to excess – in Young Girls, even a serial killer gets a jaunty tune. So Donkey Skin (1970), which could be viewed as the third of his Deneuve musical trilogy, brings back a touch of the bittersweet. It was also a film very close to his heart: not only did it serve as a tribute to Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast (1946), but Demy had long hoped to adapt the fairy tales of Charles Perrault, favorites from his childhood.

Jean Marais as the Blue King, sitting on his throne.

Jean Marais, who played the Beast for Cocteau (as well as Orpheus), here is the Blue King, living in a blue kingdom with blue-skinned servants and dwarfs, sitting on a throne which appears to be a giant fluffy cat, and listening to his daughter (Deneuve) sing to the accompaniment of a ubiquitous blue parrot. He even has a donkey which shits coins. But his wife becomes ill, and on her deathbed she has one request: that when he remarries it is with a woman more beautiful than she. Finding no one suitable in the kingdom, he sets his sights on his own daughter. (Given that Deneuve plays both mother and daughter, she should also be an unsuitable candidate. Catherine Deneuve is exactly as beautiful as Catherine Deneuve.) Distressed, the princess seeks out her fairy godmother, the Lilac Fairy (Delphine Seyrig, Last Year at Marienbad), who says she must delay her father by asking for impossible things: first a dress the color of the weather, then a dress the color of the moon, and finally a dress the color of the sun. Alas, the King has a dressmaker who can fulfill all these requests, and a director creative enough to visualize them: on the weather dress Demy projects drifting clouds on a blue sky; the moon dress is lit by white orbs; the sun dress is lit yellow, and reflects bright golden light on the King’s face as he gazes at it. Finally the Lilac Fairy tells the princess to demand the skin of the King’s prize donkey. He balks, but finally acquiesces, and after she drapes the bloody carcass over her shoulders, the fairy wishes her away into the woods. Armed with her godmother’s wand, and wearing only the stinking goat skin, the princess travels to a distant village where she acts as serving-girl to a filthy witch that spits toads out of her mouth (a lot).

Catherine Deneuve as the princess in her donkey skin.

Into her life wanders the Red Prince (Jacques Perrin, Z), from a red kingdom with red-skinned servants, etc. He falls in love with the girl everyone calls Donkey Skin, and when he returns to his palace, he asks for Donkey Skin to bake him a cake. She does, and hides her ring inside it, which he discovers by choking on it. His parents are anxious for him to find a girl to marry, so he tells them he will marry the girl who can wear the ring. Every eligible woman in the kingdom lines up before his throne, as he fits the ring to each ring-finger. The only one it fits is Donkey Skin; she sheds her skin to reveal that she is a princess, and at her wedding, father – whose incestuous urges are forgotten now that he’s fallen in love with the Lilac Fairy – arrives with his new bride in a helicopter.

The wedding of the princess and the prince (Jacques Perrin).

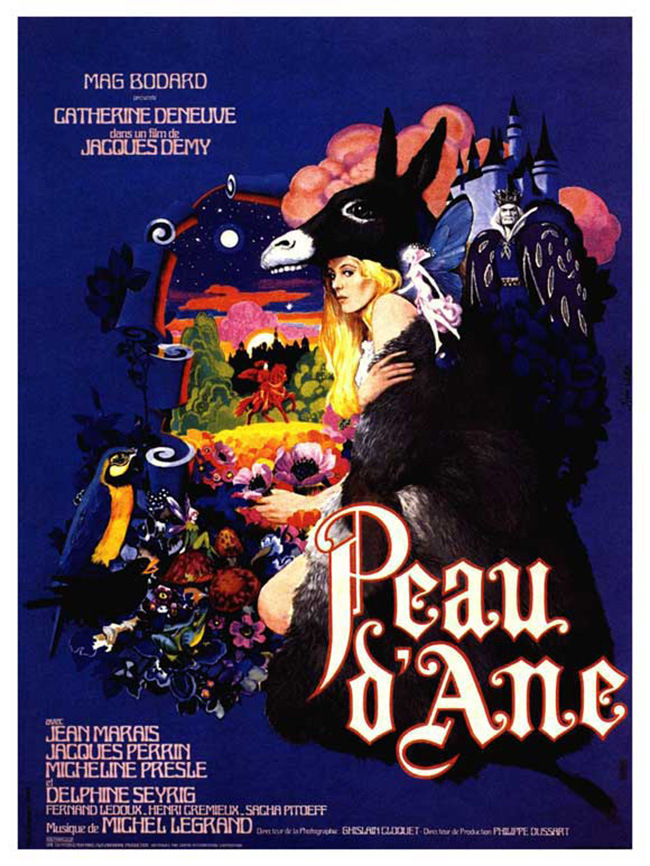

It’s a simple fairy tale, with familiar elements of Cinderella, but Demy highlights the strangeness of Perrault’s version (drawn from folk tales). He refuses to censor the incestuous overture that kicks off the narrative – in fact, he and Legrand give Seyrig a musical number on the topic, perhaps the only song ever written to explain why marrying your father isn’t a good idea. Although the film isn’t violent, the arrival of the donkey skin is a grisly sight. In homage to Cocteau’s surrealism, he has a topless statue played by a real actress (in blue body-paint) decorating the Blue King’s throne room, like the living statues in Beauty and the Beast. Jean Marais reads some of Cocteau’s poetry (about Orpheus, no less) in a failed attempt to seduce the princess. The Red Prince speaks to a rose with a woman’s mouth and eye superimposed amidst the petals. In one of Legrand’s musical numbers, Deneuve sings a duet with herself: one version a princess, the other filthy Donkey Skin. The sets are a psychedelic collage to match the art glimpsed on the fairy tale book seen at the opening of the film, as well as the film’s poster art: beds and thrones are an exploding cornucopia of Roman statues, rainbow paintings, and taxidermy – a look very unique from Cocteau, as designed by art director Jacques Dugied (Tout va bien). Donkey Skin is charming and funny, but with a sharp edge in direct opposition to Walt Disney, the fairy tale straight out of the collective unconscious. As a follow-up, Demy would move on to The Pied Piper (1972), starring Donovan. Donkey Skin is available on Blu-Ray from Criterion as part of The Essential Jacques Demy box set.