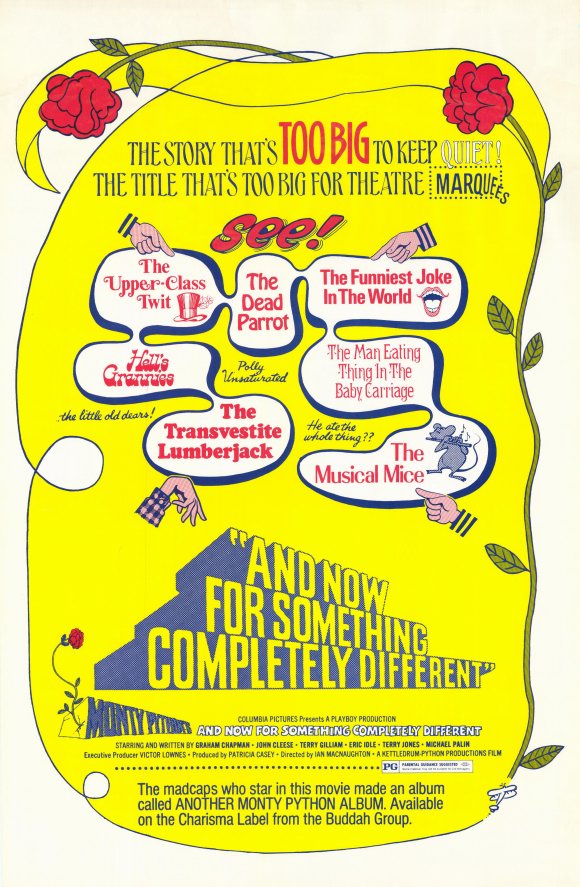

The first (and sometimes forgotten) Monty Python film was a bit like the albums and books they were putting out concurrent with the TV series Monty Python’s Flying Circus: old material presented in a different format. It’s a marketing job – get the Python brand out there. And, like the individual albums and books, it’s not a comprehensive survey of their best sketch output. Flying Circus still had two series left in it (albeit one without John Cleese), and a good share of classic sketches forthcoming. It would be nice to say that someone casually interested in Python could skip the TV series and just watch this film, but that’s not quite the case. On the other hand, it is a strong introduction to the Pythons, which is exactly what it was intended to be. This was to be the film to break Python in America. It wasn’t – not by a long shot – but that was the dream. Victor Lownes, vice president of Playboy and the head of Playboy’s European operations, was working on expanding the magazine’s brand to film. He was a fan of the Pythons’ TV series and thought it would be a hit in the States, so he approached Cleese with the suggestion of taking the group’s best sketches and re-filming them as a feature. It wasn’t a unique suggestion: in the early 70’s, with the British film industry in decline, filmed versions of British sitcoms (such as Hammer’s On the Buses in 1971) were becoming depressingly common. But translating the Pythons’ particular, unclassifiable style to film was a more exciting prospect; it’s not for nothing that the word “Pythonesque” was later added to the Oxford English Dictionary. The time was right to make a Pythonesque movie: And Now for Something Completely Different (1971).

Graham Chapman warns that the film is becoming silly.

The Python stamp is evident from the very beginning: the sketch “How Not to Be Seen” (a training film in which various people attempting to hide are blown to smithereens by a maniacal narrator, played by Cleese), followed by the Terry Gilliam-animated opening credits, followed by the words “The End,” followed by blackness. Then a chain-smoking Terry Jones stumbles onto the stage and apologizes to the audience that the film was so unexpectedly short. I’ve seen And Now for Something Completely Different in the theater, where the gag works gangbusters because it looks like Jones has really just stepped out in front of the screen. It’s an example of how the Pythons treated their various branded products with attention to the format, from Graham Chapman stopping the record to test stereo effects on their first album, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and the experiment with creating a “three-sided” record with Monty Python’s Matching Tie and Handkerchief (it worked), to the joke that if you remove the sleeve of the hardcover version of 1973’s The Brand New Monty Python Bok you will discover a hidden cover called Tits ‘n’ Bums: A Weekly Look at Church Architecture. Alas, And Now for Something Completely Different doesn’t contain as many of these inspirations as the Pythons would have liked. As Jones states in 2003’s The Pythons: An Autobiography, “I’d rather have done something original, but Vic was prepared to finance this film on the basis that he had seen people laughing at these scripts. I think very much he or John selected the sketches, so it was rather weighted to John’s material, and also there tended to be rather a lot of stuff over desks.” Cleese admitted, “I think I was a bit bossy. I probably started assembling the material a little bit as though I was in charge. I think I felt that it was a little bit my gig…” Indeed, if you take away one persistent visual image from ANFSCD, it’s John Cleese peering over a desk. The sketches co-written by Cleese often feature one character pitted in an impossible argument with another: “Argument Clinic” (which, sadly, is not in this film) being the best example of his approach. It was his writing partner Chapman who would add the inspired non sequiturs, often involving animals (deceased animals preferred).

The notorious “Dead Parrot” sketch, featuring Michael Palin and John Cleese.

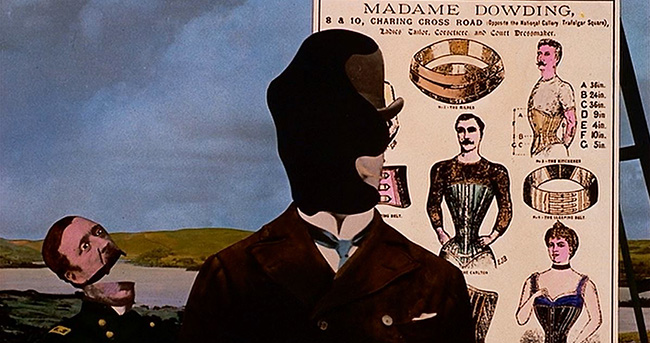

Yes, “Dead Parrot” is here, possibly the most recognizable of Python sketches. In a one-two punch that alone would be enough to make ANFSCD worthwhile, the sketch segues into “The Lumberjack Song,” as Palin the defiant pet store clerk removes his coat to reveal Palin the (secretly transvestite) lumberjack. (On his arm is Connie Booth, Cleese’s wife at the time and future co-star of Fawlty Towers.) As with the television series, one of the most enjoyable aspects is the way the Pythons manage these transitions, which is a neat method to avoid buzzkill punchlines. To take us from the “Vocational Guidance Counselor” to “Blackmail,” Palin peels off his moustache, affects a sleazy grin, and effortlessly switches personae from mousy chartered accountant to the sort of fellow who might be hanging around the entrance to one of Lownes’ Playboy clubs. But often the transition is handled by Terry Gilliam’s stream-of-consciousness cut-out animation, recreated from scratch for spectacular widescreen in the sort of laborious effort that would eventually have Gilliam abandoning animation for a career as a film director. It’s one of the minor pleasures of this big screen adaptation that Gilliam can restore the censored bit from the “Black Spot” sequence: the fairy tale prince who ignores the black spot dies of cancer, not (looped) gangrene. Gilliam and Lownes didn’t get on, and there was some dispute over how Lownes’ credit should appear (the specifics of the story vary). In the final version, his credit, in big stone letters, is awkwardly inserted into the film’s opening – which has no other credits, so it stands out like a monument to vanity. Everyone else who worked on the production is given a more memorable and inventive credit in the film’s closing titles. It’s subtle, but nothing better summarizes Gilliam’s thoughts on the man who was calling the shots on the first Python feature.

Part of Terry Gilliam’s “Black Spot” animated sequence.

For now, the official Python director remained Ian MacNaughton, the cheerful Scot who directed Flying Circus and was parodied by Cleese in the series’ “Scott of the Antarctic” sketch, where he played a manic alcoholic director acquiescing to every unreasonable demand of his stars. (I’m sure the Pythons were plenty unreasonable.) The studio scenes (all those desks) were handled in an abandoned milk depot in North London. Although the sharpness of the film stock makes everything look much better than it does on Flying Circus, it’s still a pretty drab affair, visually speaking. MacNaughton spices things up with a more dynamic use of close-ups than their live-audience studio allowed, but often he seems at a loss as to how these long sketches of dialogue and desks can be interesting. The camera will rotate around the actors – and that’s about it. It’s telling that as soon as Gilliam and Jones had the chance to direct, with Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), many of the gags were built around where the camera was positioned – pointing up at a French taunter on a high wall; watching a Trojan Rabbit brought into the castle while Arthur and his knights suddenly appear in the foreground, watching from a distance; Cleese forever approaching Swamp Castle, the same shot repeated ad infinitum, before abruptly lunging into the shot. Holy Grail was the film in which the Pythons were able to truly express their ideas on celluloid, and so, as the Pythons would have you believe, it’s their first true film. But ANFSCD is still hilarious from beginning to end, featuring excellent renditions of “Self Defense,” “The Dirty Fork,” “Expedition to Mount Kilimanjaro,” “Hell’s Grannies,” “Nudge Nudge,” and “The Upper-Class Twit of the Year,” among many others. The package didn’t sell in America as the Pythons had hoped. As Jones recalled in Monty Python Speaks, “And then of course it came out over here, and it was all the old sketches that everybody had seen on TV, so we got a lot of stick for it – especially for calling it And Now for Something Completely Different!” Nevertheless, the film was a hit in the U.K., and opened the door for more inspired widescreen Python to come.