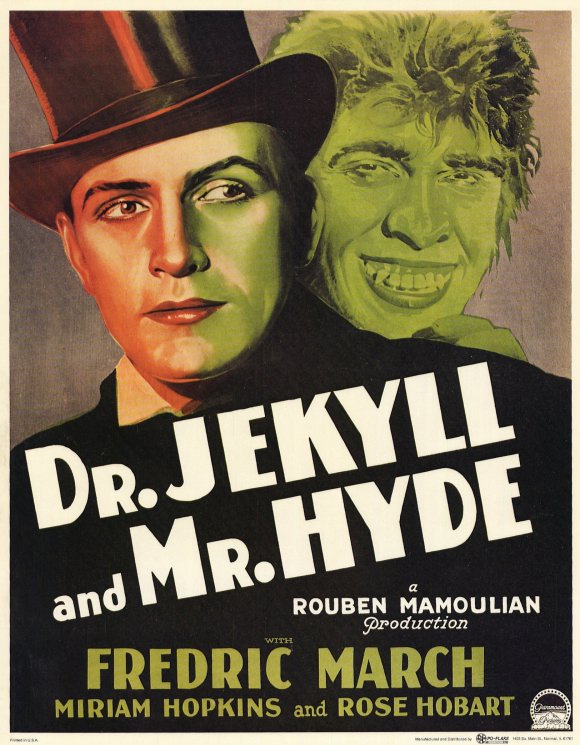

Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) immediately sets itself apart from other early talkies with a bravura sequence that relies almost solely upon visuals: an extended series of shots from the point of view of Dr. Jekyll. He’s playing a pipe organ with solemnity. He admits his butler, Poole (Edgar Norton, Son of Frankenstein), who reminds him that he needs to give a talk at the university. He follows Poole down an elegant hall. They approach a mirror, and now, as Jekyll looks directly into it, we finally see the actor playing him: Fredric March. His reflection looks back into the camera, adjusting his cravat, and Poole hands him his cape. It’s a remarkable effect, convincing the audience that there is no camera – this isn’t a film – we are Dr. Jekyll (and so, chillingly, we will soon be Mr. Hyde). If you’ve been watching very carefully, you’ll be able to figure out how it’s done. When Poole passed in front of the mirror, he didn’t cast a mirror reflection, just a glass reflection; this is simply a glass pane, and March will be standing behind it. But Mamoulian continues the subjective point of view into a carriage and finally into the lecture hall. There, he finally leaves Jekyll to drop in on the crowd and overhear their opinions of the doctor; and so it is natural when we finally see Jekyll from their vantage, and we are seated among the students. Later, in the first transformation sequence, Mamoulian will echo the technique. As Jekyll, we approach the mirror. He drinks. At the bottom edge of the lens we can see a glass lifted, as though it’s touching our lips. Then, astonishingly, he transforms before our eyes, without the use of dissolves. His eyes and lips darken; he becomes more simian. He begins to choke. It’s unlikely anyone in the audience back in 1931 could figure out how this was done. As Wayne Kinsey writes in his essential new volume Fantastic Films of the Decades Vol. 2: The 30s, it was “achieved by applying the make-up in contrasting colors. The different ‘layers’ were then picked up by rotating colored filters in front of the lens (the change in color of the picture this produced would not be seen in a black and white film).” At this point Mamoulian’s technique has reached its apotheosis: we are completely in the world of the film; we are Dr. Jekyll, and we’ve just unshackled our monstrous desires.

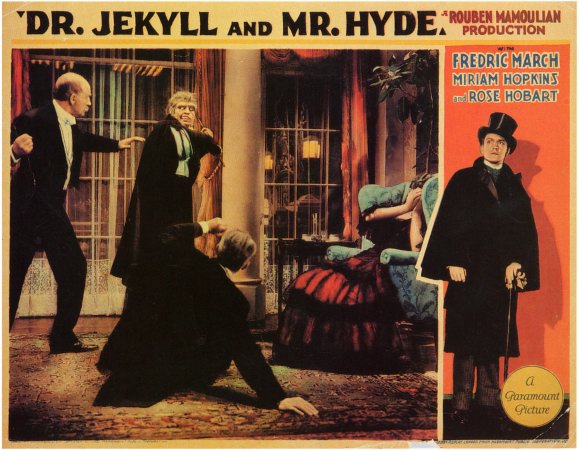

Dr. Jekyll (Fredric March) prepares for his lecture; later, Jekyll drinks his formula before the mirror, with a second glass lifted to the camera in the foreground; colored filters are rotated to expose transformation makeup before the viewer’s eyes; an edit after additional makeup has been applied reveals the newborn Mr. Hyde.

Jekyll’s lecture is delivered directly to the camera, with Jekyll towering over us with a finger pointed in the air. (This is the Hollywood version of a dry scientific talk.) “I shall not dwell today on the secrets of the human body, in sickness and in health. Today I want to talk to you about a greater marvel – the soul of man!” He has become a preacher. “My analysis of this soul, the human psyche, leads me to believe that man is not truly one, but truly two. One of him strives for the nobilities in life. This we call his good self. The other seeks an expression of impulses that bind him to some dim animal relation with the earth. This we may call the bad.” He continues, “If these two selves could be separated from each other, how much freer the good in us would be, what heights it might scale. And the so-called evil, once liberated, would fulfill itself and trouble us no more.” Of course, knowing the familiar story of Jekyll and Hyde, we know this scenario will not play out exactly the way Jekyll intends. But the talk establishes a theme which Mamoulian executes visually throughout his film: a dividing line between Jekyll’s two selves. Those selves will soon come to inhabit two worlds, London’s high society and fancy dress balls, and the smoky, boozy dens on iniquity teeming just down the street. Mamoulian uses a wipe which he halts when it’s at the midway point, drawing a diagonal line to linger, for a bit longer than one expects, on a splitscreen with two planes of simultaneously occurring action. Increasingly this effect is used to show Jekyll’s world and Hyde’s in the same shot, a visual approximation of the doctor’s split personality. At one moment, we see the woman Jekyll intends to marry, Muriel Carew (Rose Hobart, Tower of London), squeezed into one corner of the screen while in the other is Hyde’s kept woman, Ivy Pearson (Miriam Hopkins, Trouble in Paradise). In the shot, Jekyll’s head is actually severed by the dividing line, as though we are glimpsing inside his polarized psyche. And later we see Hyde – liberated, for the first time, without the use of potion – running triumphantly through a park, eager to wreak havoc, while the world he’s about to crash into – one of Muriel’s tasteful social gatherings – awaits on the other half of the screen.

Wipes as splitscreen: (Left) Ivy (Miriam Hopkins) receives money from a guilty Dr. Jekyll, while Jekyll woos Muriel (Rose Hobart); (Right) Mr. Hyde runs free while the upper crust enjoy Muriel’s party.

Mamoulian’s final tool in his arsenal is the dissolve, which is applied to the Jekyll/Hyde transformation shots toward the end of the film to put March in full monster makeup before our eyes (and which will become commonplace with The Wolf Man and similar horror movies). But the director is even more interested in the dissolve as a way to merge scenes together in that same lingering way as his wipes. The most powerful example comes in the most crucial scene in the film: Jekyll’s introduction to Ivy. He rescues her from a violent assault in the street and carries her up to her bedroom. Ivy is immediately attracted to the handsome gentleman, and attempts to seduce him – in one of the most potently erotic moments in Pre-Code Hollywood. First Ivy shows Jekyll the white flesh above her garter, and she points – “Look where he kicked me.” A few moments later Mamoulian treats us to another subjective shot, as Ivy, sitting on the bed, smiles directly at us/Jekyll, and the camera pans down to her legs as she pulls up her dress. She kicks off her shoes, then takes off her garters and throws them at the camera, laughing. Then she slips off her nylons. (Given that this is a film from 1931 and, like Dracula, there’s no musical score, one can only imagine a theater filled with the sounds of awkward swallowing.) Jekyll lifts up a garter with his cane and throws it back at her. She crawls naked into bed. During this entire scene, the subjective camera and the long moments of silence are enough to translate Jekyll’s awakening desires. But it is the dissolve away from this scene which makes it clear, on a narrative level, that Jekyll will not stop thinking about Ivy. As he leaves, we see Ivy again looking straight into the camera. She whispers, “Come back soon…soon…come baaack.” The camera pans down to her leg, which swings like a clock’s pendulum. Mamoulian begins the dissolve. Jekyll and his friend Dr. Lanyon (Holmes Herbert, The Invisible Man) walk down the steps and into the street, talking. All the while, her leg keeps swinging back and forth. We even still hear her voice, whispering, “Come back soon, yes you can…”

(Top Row) Subjective shots of Ivy, as she throws her garter and poses in bed; (Bottom Row) The pendulum swing of her leg lingers in the dissolve to Jekyll and Lanyon (Holmes Herbert), just as it lingers in Jekyll’s thoughts.

This becomes the inciting moment for Jekyll to perfect his formula and drink his potion. (Yes, Jekyll, you can cheat on your fiancée. Yes, you can have both Ivy and Muriel. “Come back soon, yes you can…”) As the potion takes effect and he swoons, the world spins around him, and dissolving, overlapping, are images that led to this moment, including Ivy’s luscious thighs and swinging leg. Hyde triumphantly shouts, “Free! Free at last!…Deniers of life, if you could see me now!” Of course, we see him now – as a primate-like beast, his inner ugliness come to the fore. As dapper as he is in a top hat and cane, when he arrives at Ivy’s hangout, the music hall, the crowd is alarmed and frightened by him. He comes to dominate Ivy, and she goes along with it out of fear for her life. He sexually abuses and beats her – we later learn he has flogged her with a whip. Jekyll, guilt-ridden at his treatment of Ivy, swears off the potion and sends Ivy money as compensation – but by now a month has already passed, and Ivy is a broken woman. She comes to Jekyll and pleads for him to save her from Hyde. These scenes are the heart of the film, and March and Hopkins are both terrific. Because Jekyll and Hyde are performed so distinctly differently, to the point that one cannot recognize they are played by the same actor, much has been made of March’s performance; he won an Academy Award for it, and deservingly so. But one shouldn’t overlook Hopkins’ performance as Ivy. She, too, gives two distinct performances: as Ivy before and after Hyde. She’s the tragic collateral damage of Jekyll’s desires. He promises she will never see Hyde again, but it’s a promise that he’s not able to keep. Watch Hopkins’ face when she sees Hyde enters her room for the last time. Once more, a mirror is involved. She lifts a glass to the mirror to toast Jekyll: “Here’s to you, my angel.” Then the door opens, and the joy drains from her face as she realizes she will never leave her side of London to join Jekyll’s world of wealth and romance. Instead her fate comes into sharp focus. As Hyde kills her, Mamoulian pans away, up to a statuette sitting on the bedside table, the figure of an angel holding a woman with grace: her dream which is now dying with her, sacrificed to Jekyll’s decision to let his devil come out to play.