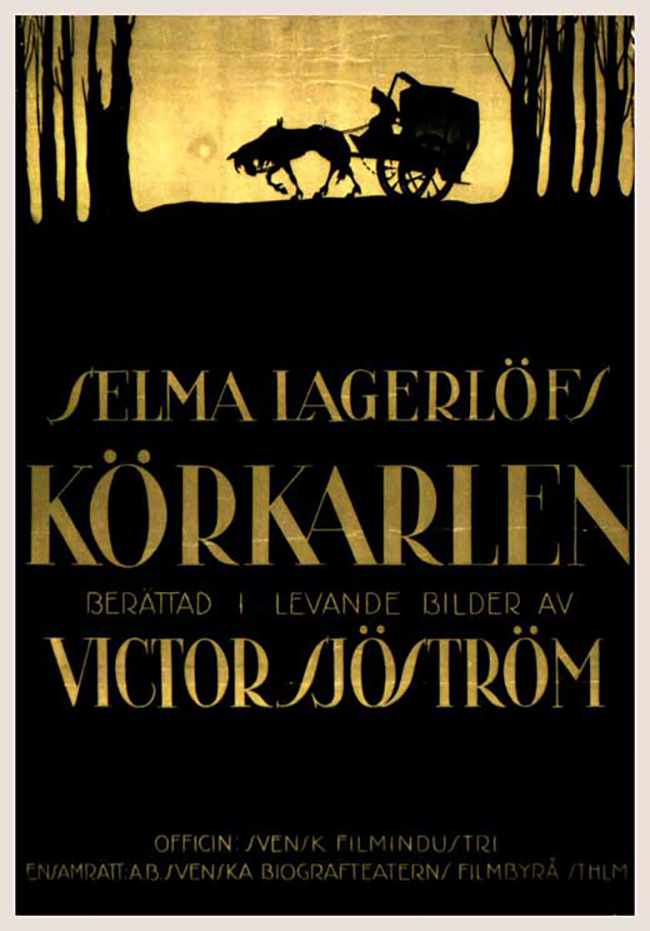

“Now you know why I’m afraid of something fatal happening to me on New Year’s Eve,” the man says. He’s sitting in a cemetery, drinking with two other vagabonds, and he’s just explained the legend of The Phantom Carriage (Körkarlen, 1921). The last person to die on New Year’s Eve is destined to become the driver of Death’s carriage, reaping souls for a full year that passes like one long night. The only reprieve for the poor soul comes when he can pass the reins at midnight on the next New Year’s Eve – and on and on, a story woven from the 1912 Swedish novel Körkarlen (The Wagon Driver, published in English as Thy Soul Shall Bear Witness) by Selma Lagerlöf. The novel was intended to educate the public on the dangers of tuberculosis, and it was the supernatural, with a strong dose of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, that became the device by which Lagerlöf delivered her message. Acclaimed Swedish director Victor Sjöström, who would later make The Wind (1928) starring Lillian Gish, was the first (but not the last) to bring Körkarlen to the screen, casting himself in the lead role of David Holm, an abusive and amoral consumptive who is made to confront his own sins on New Year’s Eve: after delivering the tale beside the cemetery, he finds himself in a brawl with his companions, who leave him dead just as the clock strikes midnight. It seems he’s talked himself right into the middle of his own ghost story.

David Holm (Victor Sjöström) threatens his wife (Hilda Borgström).

The Phantom Carriage comes for David Holm, driven by his old friend Georges (Tore Svennberg) – the subject of Holm’s tale. Sjöström used in-camera double exposures to insert the carriage, its emaciated horse, and the hooded, scythe-wielding driver as ghostly, semi-transparent invaders of the bleak landscape. In the most imaginatively evocative sequence, a man drowning in waves is visited by the slowly approaching carriage. As he sinks to the bottom of the sea, so follows the coachman, who lifts him over his shoulder and bears him back toward the surface. When Holm is summoned from death, he rises out of his own body, an image that would be frequently imitated in the decades to come. Then he joins Georges on a journey very similar to Scrooge’s with his Ghost of Christmas Past – only his past comes to life in flashbacks narrated by Holm. Holm’s married life begins in an idyll, but grows sour with his drunken carousing, contraction of tuberculosis, and (shockingly depicted) domestic abuse. With his hatred of life and pitch-black cynicism, he mocks anything in his path with a sociopathic glee: “I’m a consumptive myself,” he gloats, “but I cough in people’s faces in hopes of finishing them off!” We see him hovering over his children, while his desperate wife tries to keep him from spreading the virus – a condition that seems to have corrupted his soul. A beautiful young Salvation Army nurse named Sister Edit (Astrid Holm) takes him in one night and mends his torn coat, but in the morning he rips off the patches to teach her that there is no such thing as “salvation.” She says she will pray for him, and asks him to come visit her the following New Year’s Eve so she can see if her prayers have done any good. He agrees, but only to prove that God doesn’t answer prayers.

Holm’s soul is reaped by Georges (Tore Svennberg), the driver of the Phantom Carriage.

And it is the night he’s due to deliver on his promise which begins The Phantom Carriage. Structurally, what is most intriguing is that the film begins not with the legend of the Phantom Carriage, but with a mystery – who is this woman on her deathbed asking for David Holm? Who is Holm, and why does his wife visibly contemplate strangling the woman when she arrives? The woman is Sister Edit, and only much later in the film do we learn that she owes her tuberculosis to Holm. Despite this, she still wishes for nothing more than to reform Holm’s ways. And she blames herself for asking Mrs. Holm to give her husband one more chance – which leads to a scene of domestic violence that directly influenced Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), as many others have noted. Fearing for her life and that of her children, Mrs. Holm locks her husband in the kitchen while she hastily packs. He takes an axe to the door, chopping open a gash large enough for him to peer through, and then let himself free. Ultimately Holm will reform (and, miraculously, have his life restored by a more-powerful-than-he-seems phantom coachman), and the film becomes explicitly spiritual, but in a way that is less treacly than primal. Think Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and especially Ordet (1955), which ends with transcendent miracle. But the film also seems like an influence on a different Dreyer film, Vampyr (1932), for its eerie, dream-like spell, the ghosts of Holm and Georges wandering through nighttime streets and dissolving through walls and doors to visit Sister Edit. Appropriate for a New Year’s Eve film, it’s a film that bends beneath the weight of the shortest days of the year, a film that seems to visualize seasonal affective disorder. It also possesses a visceral sense of the end of all things opening unexpectedly into the new. It’s a film for promises and resolutions – just the other side of nightmares.