This is a proud part of the Remembering Barbara Stanwyck Blogathon (January 19-20, 2016), hosted by In the Good Old Days of Classic Hollywood and marking the anniversary of Stanwyck’s death on January 20, 1990.

The notorious Pre-Code melodrama Baby Face (1933) is an exploitation film about exploitation. The main character, the suggestively named Lily Powers (Barbara Stanwyck), must learn how to exploit herself – that is, her sexual allure – to manipulate men for her own gain: the only way to make it in a man’s world, the film implies. In a key scene early in the film, Lily, impoverished and working in her father’s sleazy speakeasy, has a conversation about Nietzsche with a German cobbler, Mr. Cragg (Alphonse Ethier, Mad Love). “A woman, young, beautiful like you, can get anything she wants in the world, because you have power over men. But you must use men, not let them use you. You must be a master, not a slave.” It’s like a perversion of the origin scene in a modern superhero film – with great power comes great irresponsibility. Though Ms. Powers is not particularly interested in reading the thick volume on the German philosopher that Mr. Cragg presses into her hands, she listens to him, smokes, considers, and then says, “…Yeah.” A hero is born. Mind you, at this point in the film it seems like the most sensible advice in the world. In the rowdy speakeasy she’s constantly groped and leered at. Her father, eager to make good with a local politician who might offer his establishment some protection, agrees to clear everyone out so the man can molest Lily without interference. Lily answers his hand touching her leg by spilling hot coffee over it: “Oh excuse me, my hand shakes so when I’m around you.” When he squeezes her waist and breasts from behind, she breaks a bottle over his head, sending him sprawling. Then she enjoys her drink undisturbed. For Lily, it’s just another ordinary night.

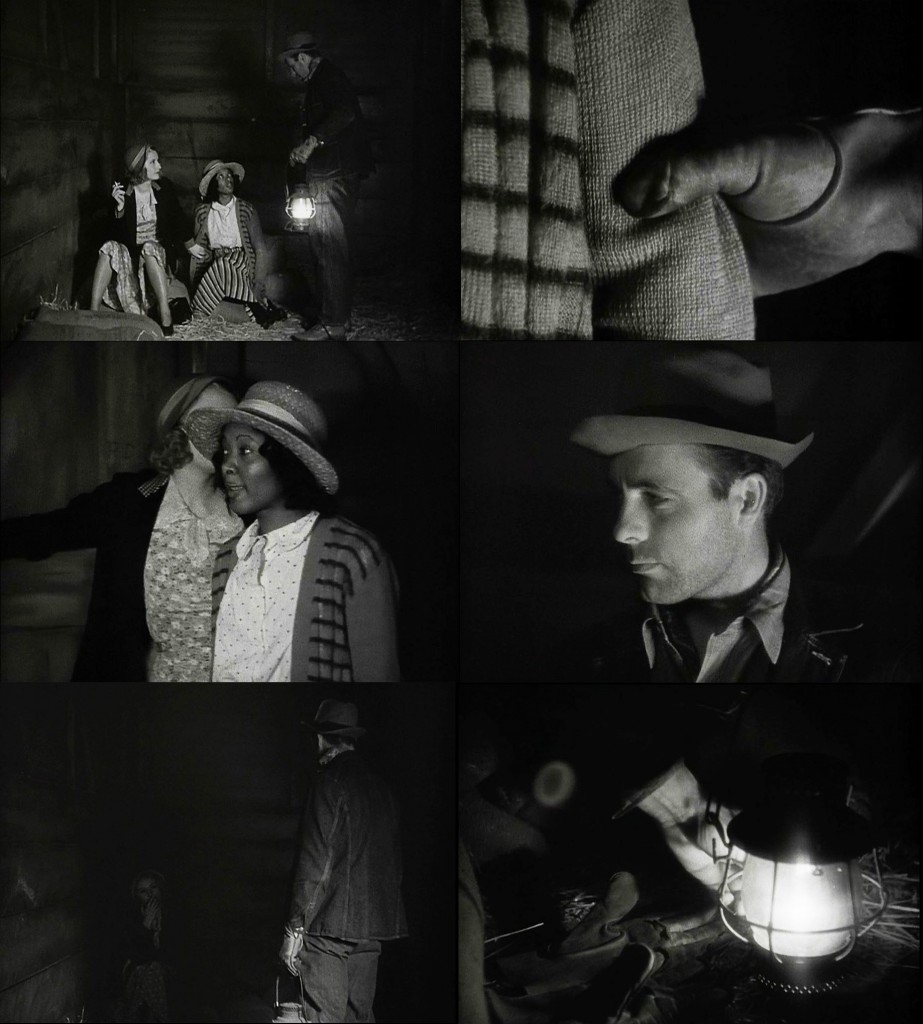

It’s difficult to imagine any other actress playing Lily Powers. Stanwyck, 26 years old and already gaining notice for her beauty and wit in films like Night Nurse (1931), Forbidden (1932), and Shopworn (1932), slips with ease into the role of someone who has been used for so long that nothing fazes her. When Cragg says, “You have power,” she responds sarcastically, “Yeah, I’m a ball of fire, I am.” But, of course, Stanwyck was making her name as a ball of fire. The screen smolders. She struts around braless but surrounds herself with a thick armor of sardonic humor, streetwise wits, and pragmatism. “Have you had any experience?” she’s asked during a job interview. She gives the man a look, then answers, “Plenty.” The look says, What do you think, bozo? The look says, You don’t have the guts to ask me what I mean by that, do you? The look says, I’m going to bluff my way through this without telling a single lie, just for the fun of it. It’s always eye-opening to witness the sexual bluntness of Baby Face and other choice movies made before the enforcement of the Production Code. (The film is available on the first volume of Warner’s Forbidden Hollywood Collection of Pre-Code films. The ninth installment in the series was released last October.) The most shocking scene in Baby Face – one of many restored in 2004 from a newly discovered uncut print – takes place in a dimly lit boxcar. Lily has smuggled herself aboard a train bound for New York City with a fellow refugee from the speakeasy, her black companion Chico (Theresa Harris, I Walked With a Zombie). When a train inspector discovers them, Lily decides to pay for their passage with her body. Chico, realizing what’s about to go down, sings the blues with an amused smile on her face and strides toward the opposite end of the car. We see the inspector’s filthy gloves dropping to the floor, and then his hand reaching to extinguish the lantern. It’s a reminder of just how gritty and adult (in the true meaning of the term) the Golden Age of Hollywood could be; it was only the Code which shaved down the edges.

Seduction of a train inspector – one of the blunt scenes that censors demanded be cut from the wider theatrical release.

To refresh your memory, this is that movie where Stanwyck applies for a job and literally sleeps her way to the top. For a short while, the film practically becomes a sex romp. Standing on the sidewalk before the towering monolith of the Gotham Trust Company, Lily tells Chico, “Boy, I bet there’s plenty of dough in this shack.” She sets out by seducing the recruiter in the Personnel Department – with his boss away at lunch, they use the empty office for their liaison. Then it’s up to the Filing Department, then the Mortgage Department, then Accounting. With each sexual conquest that allows her to climb the ladder, we fade back to an exterior shot of the skyscraper, and the camera pans upward by several foors, closing in on another office window. “St. Louis Blues” plays on the soundtrack, just as weary, amused, and knowing as the faces of Lily and Chico. We come to acquaint that theme with another low-level manager dropping his trousers. The satire here is rich. Lily has no – let’s phrase this accurately – corporate experience, but she knows that men only listen to one thing, and it’s not (apparently) their wives or fiancées. As she ascends Gotham Bank, it becomes more difficult for Lily to hide the disparity between her position and her self. She answers the phone: “Mr. Stevens’ office. No, he ain’t. I mean ‘isn’t.'” (In these early scenes in the bank, keep an eye out for a cameo by a young John Wayne.) But her survival instinct is still razor sharp. When Mr. Brody (Douglass Dumbrille, A Day at the Races), the object of one of her affairs of convenience, follows her into the ladies’ room for a quickie, he’s caught by his superior Ned Stevens (Donald Cook, The Public Enemy). Lily, glimpsed nonchalantly fixing her lipstick in the bathroom mirror, affects to pleading with Stevens: “He followed me in there. What could I do, he’s my boss and I have to earn my living. Oh, I’m so ashamed, it’s the first time anything like that has ever happened to me!” Soon enough she’s seducing Stevens away from his fiancée, and then climbing above him to find a sugar daddy in the girl’s father, Mr. Carter (Henry Kolker, The Black Room), whom she begins calling her “Fuzzy Wuzzy” while holed up in his luxurious lover’s nest.

Lily’s scandalous affairs make the headlines, with the ubiquitous skyscraper of Gotham Bank in the background.

The fun comes to a violent end when Stevens shoots Carter and then himself. This leads to a fascinating moment when Lily stands over the body. Not grieving. Thinking. She calls the police and tells them what’s happened with a tone of resignation. The bank appoints a new manager with strong family ties to the bank, a handsome young playboy named Trenholm (George Brent, The Spiral Staircase). At first Lily attempts to blackmail Trenholm and his board by selling them – rather than the papers – her diary recounting all of her affairs in scandalous detail. (Surely she hasn’t yet written a word.) But Trenholm outmaneuvers her, cornering Lily into accepting a position in the bank’s Paris branch without any extravagant payout. In Paris, with a comfortable and secure job, Lily gets the knack for succeeding without sex. (Chico is along for the ride, still acting the maid or servant. Though Lily is loyal to Chico to the end, and rewards her financially – and with fur coats – this 1930’s film just doesn’t have the inclination to depict a black woman discovering her own independence.) With the confidence that comes from being good at what she does, Lily isn’t interested in seducing Trenholm when he pays the Paris office a visit. More than that, she respects him for not being interested in seducing her. When he does begin to show a romantic interest – one established on a foundation of mutual respect – she says she’s disappointed in him. But she falls hard anyway. Subsequent melodramatic complications ensue, including a vaguely described indictment for Trenholm – “I’ve got to raise a million dollars tonight!” he declares unconvincingly – and Lily comes to a moral crossroads, where she must decide if she truly cares more for power than love. Even here, in the inevitable moralistic ending, Stanwyck is refreshingly sincere. “I have to think of myself. I’ve gone through a lot to get those things…” She does care for Trenholm, but she still remembers what being on the bottom feels, looks, and smells like: the hell of her father’s speakeasy, the powerlessness of being used and abused by men. But all her drive has brought her to a dead end, and with Trenholm’s life on the line, she finally sees the light and sacrifices her wealth for the sake of rescuing the only man who’s ever been an equal.

The girl at the top – Lily is despondent at the moral dilemma that faces her.

You could take a less feminist read of that ending than how I just phrased it. Indeed, the censor-approved, modified ending (available to watch on the DVD as part of the theatrical cut of the film – treat that cut like a supplement) feels it necessary to overstate just how reformed Lily has become, living in happy poverty with her man. But even though the film’s first half, with Lily cynically rising to the top by demonstrating what a bunch of foolish beasts men are, has a wonderfully outrageous – and feminist – jolt, it’s to the film’s credit that Lily doesn’t face the kind of Crime Doesn’t Pay resolution imposed on so many gangster dramas. She doesn’t die for her sins. In fact, in Baby Face – at least, in its uncut form – Lily never really repents, never calls what she’s had to do sins. Early in the film, penniless, she tells Cragg, “Where would I go, Paris? I’ve got four bucks.” She eventually does get to Paris, finds her soul partner, receives fulfillment – but the road to her destination requires using her body to pay for every train ticket. Ultimately, the film remains a potent indictment of the “man’s world,” and even though Lily drops her defenses in the film’s final scene, it’s only because she realizes it’s finally safe to do so. That’s the hard world of Baby Face – 1933 uncensored. This film, in fact, was so volatile that even after Warner Bros. cut and revised scenes to meet the standards of censors, it became one of the first films to be withdrawn from theaters under the enforcement of Hollywood’s self-imposed Production Code. Even today, the film is every bit a “ball of fire” as Lily Powers and Stanwyck herself.