This is the second of a two-part review. Episodes 1-4 are reviewed here.

Note: Last night I watched the final two episodes of Out 1, oblivious to the fact that Jacques Rivette had just died, aged 87. Dave Kehr’s obituary in the New York Times gives a strong overview of his life and career. Rivette’s last film was the serene and contemplative Around a Small Mountain (2009), a fitting epilogue to his work and highly recommended.

***

The trouble with writing a review when you’re only halfway through the movie should be obvious. Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 is 12 hours and 55 minutes long in its “Noli Me Tangere” cut, and its eight episodes are each as long as a feature length film, so I cut this review in half, and my previous entry gave immediate, in the moment impressions, like postcards posted during travels in foreign locales. Yet it’s still one big film – a “game of great patience,” as a card game within the film, “Thirteens,” is described. Upon commencing the Fifth Episode, I began revising my impressions at once. Slowly I began to understand concepts which were still vague to me in the first several hours. A single line of dialogue might open wide an idea that I’d been neglecting, but which was clearly on the minds of the actors and director. Meanwhile, story threads seem to come together – this, from a film which spends its first half making the viewer wonder if there is even a story, teasing narrative like a dominatrix. (You think there’s a conspiracy of the Thirteen alive in 1970’s Paris? You’re furiously jotting notes on which characters are connected? Very well, here is another twenty minutes of theater improv exercises followed by a rigorous analysis of those exercises.) The Sixth and Seventh Episodes perhaps represent the height of Out 1‘s story. But then Episode Eight begins to withdraw the love and attention before pressing the viewer’s face to the floor beneath its high-heeled leather boot. It’s an enigma to the end. In fact, it’s very much like those improv exercises you’ve been watching. After the ending credits, you half expect Michael Lonsdale to step in front of the camera one final time to offer notes on where the actors were in perfect harmony and where everything fell apart. Rivette doesn’t mind his sprawling film being a little messy; in fact, he prefers it. This wasn’t a scripted film, after all, but one that was sketched, giving the actors free reign to explore Rivette’s ideas and to bring plenty of their own.

“Fifth Episode: From Colin to Pauline”: a production of “Seven Against Thebes” becomes “Seven Against Paris” as the troupe attempts to catch a thief who’s somewhere in the city streets.

But for just a bit let’s talk about plot anyhow – because there is one, just as there is a network of connected or rhyming themes that tug the viewer along. Granted, much of the plot is absurd, gestures at film noir with big fat quotation marks to either side. (Yes, this is definitely a film of the French New Wave.) When last we left Jean-Pierre Léaud’s Colin, he was struggling to decipher coded messages left to him, pulling out references to Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark and, most importantly, Balzac’s 1833-1835 novel History of the Thirteen, a book which is ostensibly about an occult-like conspiracy of thirteen men who control Paris. (I say “ostensibly” because, if you’ve read the book, you know it’s like a concept album that doesn’t sustain its concept past the first two tracks. Earlier in Out 1, Éric Rohmer says as much…) He finally has his breakthrough when he realizes that the final letters of each line in a passage spells, acrostically and backwards, W-A-R-O-K, the name of a well known professor, whom he immediately goes to visit. Warok (Jean Bouise, Z) earlier received a visit from the other questing free agent, Frédérique (Juliet Berto, Celine and Julie Go Boating). Frédérique, having stolen letters between members of the Thirteen in the Fourth Episode, is now trying to sell them for a profit. Her attempt to blackmail one of the women in the letters, Lucie De Graff (Françoise Fabian, Belle de Jour), goes badly on the rooftop of the Moulin-Rouge, although she is received with greater interest from Pauline (Bulle Ogier, also of Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating), the owner of the psychedelic boutique L’Angle du Hasard and the object of Colin’s crush. Pauline – whose real(?) name, we will soon learn, is Émilie – is worried that the leader of the Thirteen, an architect named Pierre, has done something sinister to another member, Igor, who may or may not be in Mexico, and may or may not be alive. In the stolen letters Pauline-Émilie sees further evidence of Pierre’s villainy, and in revenge plots to bring evidence of Pierre’s fraudulent architectural dealings to the press, exposing and ruining him. Her scheme comes to the attention of members of the Thirteen who side with Pierre: Thomas (Lonsdale), Sarah (Bernadette Lafont, A Very Curious Girl), and Etienne (Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, The Crook). Together they decide to put a stop to Émilie as well as her sympathetic friend Lili (Michèle Moretti, L’amour fou), who is in hiding at a sprawling beachside manor called the “Obade.” This was once the gathering place of the Thirteen.

“Seventh Episode: From Émilie to Lucie”: Thomas (Michael Lonsdale), Lucie (Françoise Fabian), and Etienne (Jacques Doniol-Valcroze) discuss Émilie’s scheme.

And, by this point, the viewer knows there really is a Thirteen – it’s not just the imaginings of the infantile Colin and Frédérique. Or, rather, there was a Thirteen – two years ago. Rivette toys with the ambiguity of the Thirteen’s existence even after confirming the conspiracy theory. It seems that the Thirteen was an idea based upon Balzac’s novel, conceived largely by Pierre, a man of great imagination and “lack of seriousness.” “He’s always believed in the ideal city,” Lucie says. Which implies Pierre wanted to use a Thirteen-like society to reinvent Paris. The events in France of May 1968 hover like a flame over Out 1: indeed, the Thirteen was just another facet of that failed revolution. Shortly after being founded, the 1968 Thirteen dissolved and went their separate ways, now limited to occasional correspondence or chance meetings. Lili and Thomas worked on their separate theater companies, just as they now are both attempting separate Aeschylus plays. As Thomas tells Lili toward the end of the film, he decided to do everything in opposition to her; while her rehearsals for Seven Against Thebes have been carefully composed, each actor required to match their movements to percussion played on a tape recorder, Thomas’s group explores improvisation to the extent of losing the original concept of Prometheus Bound. “I don’t know if you’ve noticed,” Thomas muses at one point, “but Prometheus has gradually disappeared.” When Colin finally discovers Thomas’s theater and, posing as a reporter, asks him questions not about the play but about History of the Thirteen, Thomas keeps asking him what this has to do with Prometheus. He becomes disturbed not just by Colin’s invasion of their secret society, but of that question – what does Prometheus have to do with the Thirteen? He asks that of another member of the group, almost obsessed with the idea. I may have one answer for him. While paging through the Balzac book for this review, I came upon the Bibliography which mentions a 1965 biography by André Maurois, Prometheus: the Life of Balzac. No doubt Rivette had it on his bookshelf. Prometheus, Balzac, and May 1968 are thrown into a soup, ingredients for Out 1‘s extended improvisation. Frequently inspired connections do arise, although the sprawling, stubborn film refuses to coalesce into a whole for more than fleeting moments.

Frédérique (Juliet Berto) enjoys a moment in the park with her new lover, Renaud, in the Seventh Episode.

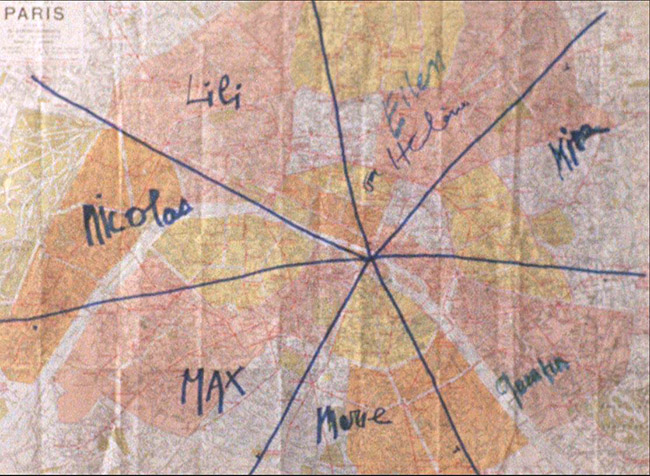

Rivette’s work frequently expressed a love of live theater in general, and experimental theater in particular. He enjoyed erasing the boundaries between the audience and the players, engaging or assaulting the audience, like Antonin Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty – as Rivette expert Jonathan Rosenbaum points out in his essay accompanying the new Blu-Ray of Out 1 – or like the later Panic movement of Alejandro Jodorowsky, Fernando Arrabal, and Roland Topor (though Rivette never embraced the grotesque). Many of his films are determined to remove that divide between the stage and the theater seats, notably his underrated Love on the Ground (1984), a surreal comedy about a theater group that performs only in homes and apartments. In Out 1, there are many delightful moments when the actors are let loose among the real-life citizens of Paris – particularly when Lili’s group, having given up on its production, set out to find the thief, Renaud (Alain Libolt, Army of Shadows), who stole a million francs from Quentin (Pierre Baillot, Mr. Freedom). Seven Against Thebes becomes Seven Against Paris, the play moved into the broader stage of Paris, as the seven actors divide a city map among themselves using a black marker. (The divided map recalls the title of Rivette’s first film, Paris Belongs to Us. It also echoes the Paris-as-board-game scheme of his 1981 film Le Pont du Nord, which also features a marked-up map.) As the actors ask Parisians, “Have you seen this man?” – holding up a picture of Renaud – the passers-by smile shyly or duck to avoid them, occasionally glancing at the camera. As so often in Out 1, the film becomes a documentary about itself. Léaud, with his harmonica, even more aggressively interacts with real people, playing his toneless music loudly in their faces as he peddles for money. In one episode, as he recites the coded message over and over as a mantra, he acquires a following of small children fascinated by his behavior. I doubt Rivette or Léaud planned that, but it’s one of the many moments that make Out 1 feel so alive, risky, the high-wire act of improvisation.

Quentin (Pierre Baillot) tracks the man who stole his money.

Colin isn’t just hunting the Thirteen, he’s hunting Lewis Carroll’s Snark. The fantastic may indeed exist in this world, the magical pulled out slowly, emerging in the final episodes. In a David Lynch moment, Sarah begins to give Colin instructions in dialogue that Rivette runs backwards. It’s suggested on multiple occasions that the Thirteen have magical powers, and we see potential evidence, if you’re willing to believe. Outside the shop, Pauline-Émilie apparently casts a spell on Colin, forming a magical barrier which he cannot cross, allowing her to safely depart while he pushes up against the wall in a mime act. An almost existentially terrifying scene, in the manner of Ingmar Bergman, occurs in a bedroom at the Obade: Sarah summons a psychic assault upon Pauline-Émilie, staring at her, asking the same questions over and over, while her victim tries feebly to resist. As for Lewis Carroll, an explicit reference can be found in the film’s many mirrors (another of Rivette’s pet motifs). In the most startling shot in the film, Pauline-Émilie enters a room in the Obade where, it’s been speculated, Igor might be hiding out. She’s afraid of the room, afraid of Igor (or his ghost?), even though she’s trying to avenge his theorized death. But inside she only finds a table, a window looking out upon the blue sea, a bust, and two mirrors facing each other. As she glances into the mirror, she sees a Looking-Glass portal receding into infinity. But then she moves in front of it, and we see Pauline facing herself – or Pauline facing Émilie, perhaps, since with an alias she’s already granted herself her own double. We might be reminded of the mirror games played as acting exercises a couple of times in Out 1 – only in this case she is not staring down a fellow actor, but herself. (As Rosenbaum points out, the title of the Sixth Episode is “From Pauline to Émilie,” the only example of an episode title referring to two versions of the same character.) Often in Rivette’s films he paired female doubles, most famously with Celine and Julie, and the fact that Pauline is her own double makes for a fascinating riddle in a lengthy film that’s full of them. This image, of Pauline-Émilie alone with a repeating loop of her selves in the mirror, reminds me of Rosenbaum’s incisive observation of the film’s interest in solitude vs. groups: “Virtually all of Out 1 can be read as a meditation on the dialectic between various collective endeavors (theater rehearsals, conspiracies, diverse counter-cultural activities, manifestos) and activities and situations growing out of solitude and alienation (puzzle solving, scheming, plot spinning, ultimately madness) – the options, to some extent, of the French left during the late 1960’s.”

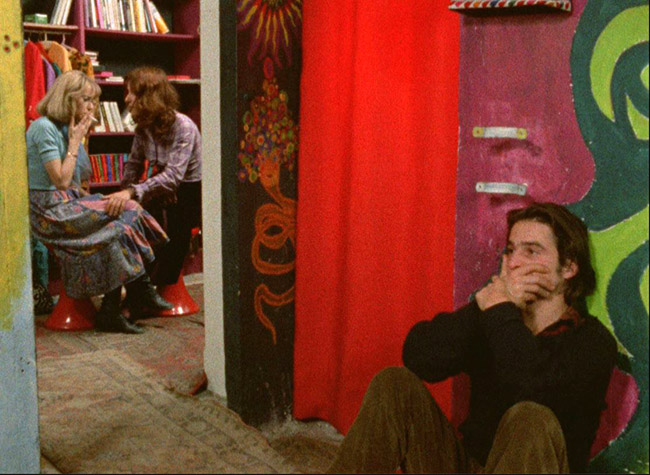

The “outside” in Out 1 – Colin (Jean-Pierre Leaud) is isolated even when he tries to join with others – the Thirteen, or at least his love Pauline/Émilie (Bulle Ogier, smoking in the next room).

In the Eighth Episode, “From Lucie to Marie,” we begin to see the collectives fall apart as characters become isolated, either to revert to a previous state or to be destroyed. In the case of Colin, his efforts to join with his love Pauline-Émilie are rebuffed, which she comes to regret in the hostile isolation of the Obade (one of Rivette’s many haunted houses, and one that seems to embody isolation within a group – people come to gather there, but no one seems to find comfort). She realizes she misses him, and the film leaves her with her regret, the two would-be lovers still separated. As for Frédérique, she finds a lover in the thief Renaud, but when he says he’s given the stolen money to a secret society called “The Companions of Duty” (which comes from The History of the Thirteen), she believes they are a more sinister sect called the “Devourers” (ditto). She dons a mask like a character from an old French serial and ends up getting accidentally shot by Renaud – one of the few moments of physical violence in Out 1, and the only killing, though her blood is stage blood, as deliberately phony as anything in one of Jean Rollin’s early 70’s vampire films (which also paid tribute to serials). But Rivette affords more tragedy to the fate of Thomas, who has become, in Pierre’s absence, the one most devoted to protecting the idea of the Thirteen and the most manipulative of the film’s many characters. As Pauline-Émilie and Lili tell each other, he is a “Mephisto,” given to mesmerize others – appropriate for the one commanding the rituals of the theater exercises. But the final images of Out 1 see Thomas broken upon a beach, abandoned by the last of his followers, the dream of the Thirteen dead. Perhaps appropriately, Out 1, in its final cut, comes to a close just five minutes short of what would have been a schematically perfect thirteen hours. It’s like the 1968 Thirteen, almost formed, but not quite, the dream dying along with the Parisian ’68 revolution. In the Seventh Episode, Warok tells Colin that the Thirteen is just a joke. “A joke?” Colin says in wonder. “But in that case the entire magical, mysterious world in which I move would be shattered in a moment.” He concludes: “And that’s not possible.” The bubble does finally burst, and Colin turns his back on the idea of the Thirteen, returning to peddle at cafés with his harmonica in his teeth – but before that fall it’s Rivette’s extraordinary feat of illusion, sustained for twelve hours and fifty-five minutes.