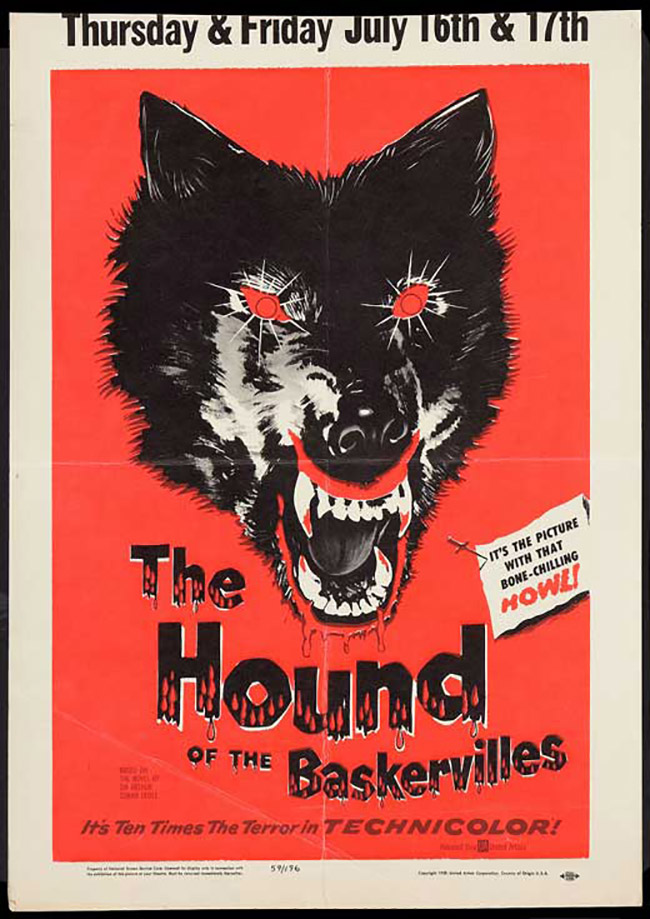

Although it’s been available in Blu-Ray format for some time in the U.K., Hammer Films’ sole adventure with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous detective is now available in high definition in the U.S., on a limited edition from Twilight Time. The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959), as many have pointed out, ought to have launched a Sherlock Holmes series right alongside Hammer’s Dracula and Frankenstein pictures. It was poised to do so: both franchise-starters, The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), had just been released, each spotlighting the irresistible trifecta of stars Peter Cushing & Christopher Lee and stylish director Terence Fisher. But although Hound of the Baskervilles benefited from the momentum – it’s another instant classic – the studio decided to chase its horror muse (or, rather, the receipts), to legendary results. Their Sherlock Holmes film became a tantalizing what-if. Peter Cushing was born to play Sherlock Holmes, looking strikingly similar not just to Doyle’s description but to the original illustrations from Strand Magazine, and his effortless authority and condescension, coupled with his charisma, make his donning of the deerstalker a truly satisfying experience. As I’ve mentioned before on this site, even though Hammer decided not to make another Holmes film, he wasn’t through with the character by a long shot. Cushing went on to a Sherlock Holmes TV series a decade later, and one of his very last on-screen roles was as the title character in the TV-movie Sherlock Holmes and the Masks of Death (1984), directed by Hammer veteran Roy Ward Baker (Quatermass and the Pit).

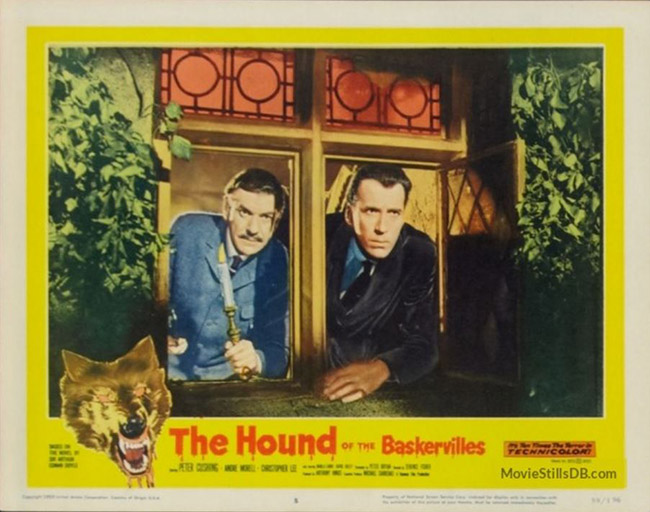

Lobby card: Dr. Watson (André Morell) and Sir Henry Baskerville (Christopher Lee) watch the moors.

Obviously, for a studio that was finding blockbuster success with its horror output, Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novel was an attractive property. The idea of a supernatural hound stalking the moors at night and threatening a cursed family makes for a potent Gothic. Although Hammer horror got its start with X-certificate science fiction (1955’s The Quatermass Xperiment being the watershed), both The Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula were period Gothics, still proudly bearing their X-certs. The Hound of the Baskervilles – which would also bring back composer James Bernard and a bombastic theme reminiscent of Dracula‘s – plays up its horror elements, even though it received a more family-friendly A-certificate. The opening of the film is an extended prologue illustrating the backstory of the Baskerville curse, which culminates with a young servant girl being chased by a pack of hounds to some old ruins on the moors, where she’s brutally stabbed by a Baskerville (David Oxley, Bonjour Tristesse) wielding a sacrificial dagger. The way the scene is staged, it almost appears that he’s going to rape her; when he reaches for the dagger, he at first appears to be unbuttoning his pants. The aura of sexual violence is all that matters, at any rate. A few years later, when director Fisher made The Curse of the Werewolf (1961), he upped the ante with an even longer prologue of exposition and more explicit sexual violence, though to the same end, establishing the nature of a family curse rooted in debauched crimes of the upper class. Hammer also adds an encounter with a tarantula, and the moors become a horror-ready landscape of fog and bogs. Cushing’s Holmes speaks frequently of the power of evil as an almost supernatural force, drawing comparisons with the actor’s portrayal of Van Helsing.

Sherlock Holmes (Peter Cushing) examines a dagger while Dr. Watson looks on.

Yet what impresses me the most about The Hound of the Baskervilles is that Fisher and screenwriter Peter Bryan (The Brides of Dracula, The Plague of the Zombies) allow Doyle’s original mystery to shine through without much fiddling. The novel presents a solid, timeless mystery, and this adaptation presents it faithfully, apart from some understandable tweaks to make it more cinematic, such as the prologue, the aforementioned shocks, and a couple hot-and-heavy scenes between Lee and Italian actress Marla Landi (The Pirates of Blood River). (Incidentally, notice that when Lee kisses Landi, he does it in full-on Dracula mode, pecking her up and down her face. One almost expects him to work his way down toward the neck.) The faithfulness even extends to Doyle’s unusual choice to allow Holmes to be absent for a large portion of the narrative; hero duties are turned over to the unassuming Dr. Watson (André Morell, one of Hammer’s most underrated MVPs; watch him in the heist thriller Cash on Demand). This also allows Lee’s portrayal of the frail but noble Sir Henry Baskerville to shine: it’s always nice to see Lee play someone who’s not a villain. Cushing’s reappearance and subsequent adventures, including a close shave in a collapsing mine, are suitably satisfying, but one thing that can be said about Hammer’s Hound is that it’s generous with its ensemble – extending to Francis De Wolff (From Russia with Love) as Dr. Mortimer, Ewen Solon (from the Cushing-starring 1984) as Stapleton, John Le Mesurier (The Italian Job) as servant Barrymore with Helen Goss (The Sword and the Rose) as his wife, and Miles Malleson (The Thief of Bagdad) providing comic relief as a loose-tongued, sherry-drinking, tarantula-collecting Bishop.

Marla Landi as Cecile.

This was the first full-color Hound, luscious in its color schemes, handsomely mounted even if Hammer fans will quickly recognize the oft-recycled Bray Studios sets. It looks more expensive than it was. The visual splendor complements the intellectual focus of the film, the emphasis on its cracking dialogue. Cushing, as with his Van Helsing or Dr. Frankenstein, springs from one end of the set to the other, now wielding a magnifying glass in his hand, or a small pistol. Shadows loom in the cavernous Baskerville manor, and the repeated warning to stay off the moors at night, with its werewolf movie overtones, is underlined by perilous cliff drops and screams of unwary travelers trapped in the oozing black mire. With so much attention given to the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce films of the 30’s and 40’s, the long-running Jeremy Brett TV series of the 80’s and 90’s, and the anachronistic Sherlock and Elementary, it’s nice to witness the rising reputation of this sumptuous 1959 film, which doesn’t enjoy the benefit of sequels or full broadcast seasons. How can you resist this film’s introduction to Holmes? After the extended prologue of horror and murder, the narrator, Dr. Mortimer, is stunned to see that Sherlock, slumped in his chair and puffing on his pipe, has hardly been paying attention. He’s looking for the meat of the mystery, not the fancy dressing. Thankfully for us, Fisher’s film provides both in large portions.