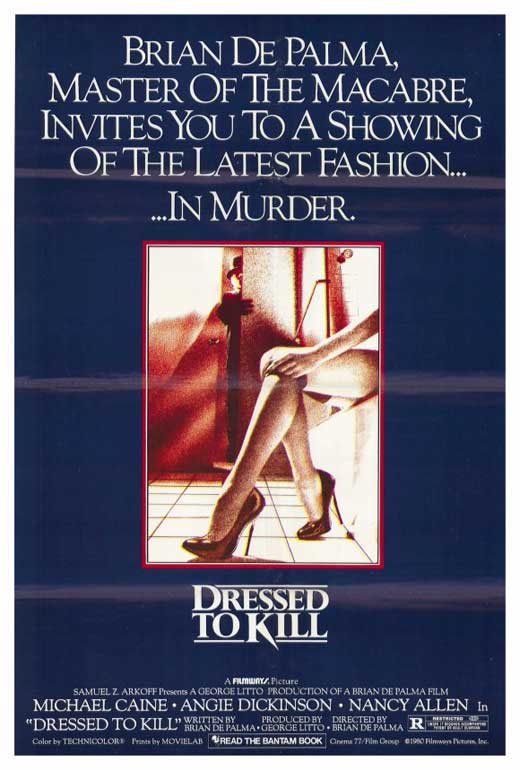

After the psychic thriller one-two of Carrie (1976) and The Fury (1978), Brian De Palma returned to his scrappy roots with the comedy Home Movies (1979), shot using his film class as the crew. Dressed to Kill (1980), then, refocused his craft on that for which he was best known: virtuoso, intensely cinematic, gleefully manipulative suspense. It’s a problematic film, as I’ll go into in a bit. But the film is an exercise in craft, an experiment in technique, spartan in its construction. If a critic didn’t like De Palma before, Dressed to Kill was unlikely to alter opinions. Once again he mines Hitchcock for inspiration, and this time the mine in question is Psycho. A heroine who’s killed off early? Check. A cross-dressing killer? Check. A shower scene? Two of them, in fact. For De Palma’s fans, by this point the Hitchcock allusions became part of the fun. Much like Home Movies, Dressed to Kill could be viewed as an extension of his film class, a thesis on the Master and a demonstration of how effective purely cinematic techniques still are. At the same time, De Palma applies his own stamp: slow motion, split screen, split focus, a rich character ensemble, steamy sex, and voyeurism that serves as meta-commentary, a recurring theme in his work that’s inseparable from Hitch. By now, parsing has become pointless. Even despite a hefty flaw which prevents me from ranking it higher, Dressed to Kill is one of the purest distillations of De Palma. Only removing all the film’s dialogue and relying entirely on visuals would have pushed it further down the alley it’s exploring. In fact, I would love to see a re-edited silent version.

Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson) is assaulted in the shower.

The doomed heroine, Kate Miller, is played by Angie Dickinson, introduced masturbating in a hot shower while watching her unaware, shaving husband. Dickinson was a year shy of 50. She had been the star of the groundbreaking Police Woman in recent years, but her glory days as a film star were well behind her (Rio Bravo, The Killers, Ocean’s 11). Although the scene is revealed to be just a sex dream (which ends as either a nightmare or a rape fantasy, depending on your read), it’s both a jarring and a daring introduction for a middle-aged actress, particularly one as well known as Dickinson. Her character is given no context but this: disrobe, touch herself graphically, let the romantic music of Pino Donaggio (Don’t Look Now, Carrie) dominate the soundtrack. You could be cynical about the fact that a much younger woman, a Penthouse Pet, doubles for Dickinson in the close-ups, but to me it feels like a comment by De Palma on the role of voyeurism in the intrinsically artificial art of filmmaking. Four years later he would even devote an entire film to the subject: Body Double (1984), whose amusing ending credits serve as a deconstruction of Dressed to Kill‘s most famous scene. Well, your mileage may vary. One thing is for certain: at least in the uncut version of the film, the softcore close-ups pushed the envelope for mainstream filmmaking; although there are certainly “erotic thriller” antecedents, from this moment is born Basic Instinct (1992) and all of its 90’s copycats. But don’t lose sight of the fact that the scene transitions to a most un-erotic shot of Dickinson in bed while her husband humps her like a machine, then rolls over. She expresses her lack of sexual fulfillment to her therapist, Dr. Elliott (Michael Caine), a scene which would be entirely unnecessary – De Palma just demonstrated this with an almost comic perfection – but for the necessities of the plot. A similar functional role drives the scene in which Kate bonds with her computer genius teenage son, Peter (Keith Gordon, fresh off Home Movies), but it’s also a warm, human moment, which helps cement our sympathies for Kate before she embarks on her quest for a sexual adventure (shades of Eyes Wide Shut).

Kate flirts in the art museum.

What follows may not have made the same waves in pop culture as Dickinson’s steamy shower, but it’s one of the most exciting sequences in De Palma’s filmography, and the real reason to watch Dressed to Kill. During a daytime trip to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (shot inside the Philadelphia Museum of Art), Kate engages in a flirtatious pas de deux with a handsome stranger, a nine minute sequence with no dialogue. At first it’s unclear whether the stranger has sat next to her out of romantic interest or simply at random. We are not sure; she is not sure. They separate, find each other again; she chases him through gallery after gallery while others pay no mind. We see him in the background of certain shots, spotting him like a Where’s Waldo, playing the game; and when he makes contact with a joking gesture, she shrinks away, misreading it, thinking she’s being mocked. She reconsiders. She tries to find him again, and can’t…and so on. De Palma uses split screen to illustrate her thoughts. But he’s also playing another, secret game: a killer is stalking Kate, and can be briefly glimpsed during the long takes and the twisting Steadicam shots. Somehow, all this can culminate in ecstatic public sex in a taxicab and we’re prepared to just go with it – like Kate. In retrospect it’s easier to see this showstopper as a demonstration, a film class lecture on how to play the audience like a fiddle, though it’s too much fun, too effective, to come across as academic. It also spells out ground rules for enjoying the rest of the film. Embrace the style, the moment. It’s a ride. If you see traces of Marnie, great. This or that was borrowed from Psycho, fine. Go with it.

Michael Caine as Dr. Elliott.

Which is, perhaps, the only defense for the film’s dated and offensive ideas about what it means to be transgender. It’s a weak defense. De Palma was inspired to write the film after seeing Nancy Hunt, who had undergone gender reassignment surgery, being interviewed on The Phil Donahue Show. A clip is used in the finished film. De Palma’s screenplay klutzily and ignorantly posits the idea of a transgender individual (transsexual, in the parlance of 1980) coming into conflict with her sexual desires and acting out by murdering the objects of that unwanted desire. In other words, Caine’s Dr. Elliott, who secretly identifies as a woman named Bobbi, kills Dickinson because she’s stimulating to Caine as a man. In Michael Koresky’s essay included with the Criterion release, he defines this as “the film’s pulp conception of transgender identity” and that you shouldn’t make “the mistake of taking it all too seriously.” While the film is certainly self-conscious pulp, in the same disc’s interview with De Palma (by Noah Baumbach, co-director of this year’s doc De Palma), it’s clear that the director was so intrigued by the Nancy Hunt segment on Donahue that he was using his screenplay partly as an exploration of the idea of being a “transsexual.” Perhaps Psycho gets away with it because it’s clear Norman Bates is his own unique subcategory; think of how often a character is described as being “like Norman Bates,” or the fact that he is taking on his mother’s personality specifically when he plays dress-up. He’s also just a richer, more complex character than Caine’s Dr. Elliott, thanks in large part to Anthony Perkins’ nuanced performance.

“Bobbi” strikes.

This element of Dressed to Kill bothered me on my first viewing several years ago, and it bothers me on this viewing, too. It’s distracting, like when you’re watching an enjoyable old movie and casual racism intrudes (in particular, I’m recalling two memorable instances at revival screenings of 1930’s comedies, where inescapable racism brought a laughing audience to an awkward silence). It’s especially distracting because it is such an unavoidable part of De Palma’s film. I hesitated writing about Dressed to Kill for this reason; but hell, there’s a much more spirited condemnation by Sherilyn Connelly at SF Weekly: “I would be perfectly happy if nobody ever watched you again,” Connelly addresses the film, “because you’re deeply transphobic.” I don’t feel the film shouldn’t be watched. There’s too much that’s worthwhile in it, and I advocate watching interesting movies in context of what makes them problematic. In fact, much of this website takes up problematic films and salvages the pieces of them that feel vital and interesting. But is it transphobic? Yeah. It is. And it wouldn’t be made today. Also distracting – and, for 1980, a little bizarre – is a scene in which Nancy Allen’s streetwalker, Liz Blake, is terrorized on the subway by a black gang. De Palma exploits the idea of a white woman chased by violent and lusting black men, and even if it’s just for a gag conclusion (a different danger intervenes, Bobbi the slasher, and the gang shrinks away in fear), it’s disappointing that a racial element is even considered for his arsenal of suspense devices. If I’m squirming in my seat during this scene, it’s for a completely different reason.

Nancy Allen as Liz Blake.

So – there’s all that. When the film was released, it was picketed, but not for any of the issues I’ve mentioned. The film was seen as glorifying violence against women. It’s a complaint that almost seems quaint in light of the many Friday the 13th films to come; De Palma, by contrast, treats his women quite lovingly here (Allen’s portrait of Liz is very charming), and Dickinson’s fully-realized character is only dispatched like Janet Leigh before her. I appreciate Dressed to Kill as a style-for-its-own-sake thriller that tells its story almost entirely with visuals. Many moments in the film, isolated, belong in the director’s highlight reel. There’s Keith Gordon setting up a hidden camera to take shots of an apartment building, told without explanation – we have to figure out what he’s doing by watching him, and once again De Palma serves up a compelling justification for split-screen. There’s the final shower scene with Allen, which is unnecessary but brilliantly executed nonetheless. In fact, this closing sequence is probably the best argument for “don’t take any of this seriously,” since it has no functional role for the plot, is a complete fake-out, and sprawls across a length of time that would be unjustifiable if it all weren’t so transparently clear that De Palma just wants to set up another big jolt for the audience. I like watching De Palma at work like this. For that reason, I’ll probably still come back to Dressed to Kill, even if I have to slice it up with a razor to isolate the bravura moments from those that I’d rather discard.