Ken Russell’s major Hollywood foray, Altered States (1980), was a big-budget, FX-driven, mind-bending science fiction fable centered on isolation tank experiments: a 2001 for the New Age set. Though the film made its money back, it ended Russell’s shot at the Hollywood big time. The British director was already a moneymaker back home, where audiences appreciated that they had their own home-grown Fellini, but the enfant terrible (as British obits would later describe him) was not accustomed to compromise or Hollywood politics. He feuded with screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky and banned him from the set, and Russell’s reputation took a hit in the process. He returned to Europe, directing operas and short films. A few years later he was flying out of L.A. having failed to find any new Hollywood projects, and aboard the plane read a screenplay by Barry Sandler (The Duchess and the Dirtwater Fox), a thriller about prostitution, infidelity, and violent sexual obsession. Soon he was flying back to America, agreeing to make Crimes of Passion (1984). Sandler produced, and Roger Corman’s B-movie production company New World Pictures stepped up with a modest budget. It would be Russell’s last American film.

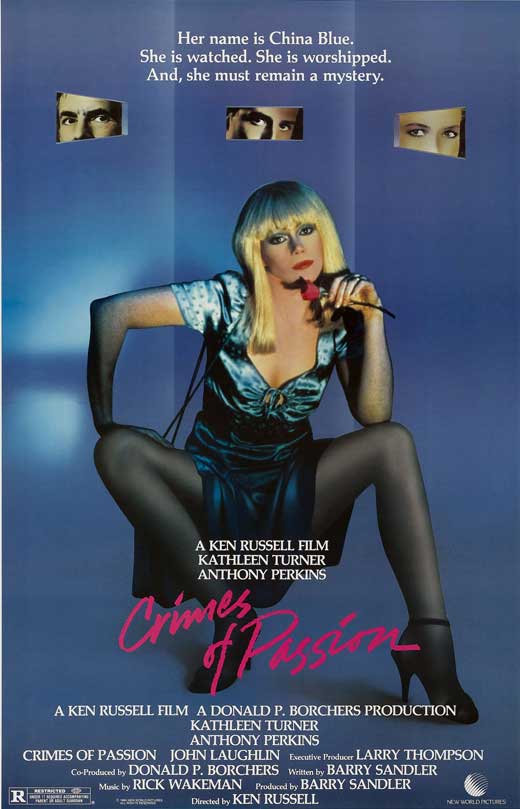

Kathleen Turner as Joanna Crane as China Blue as “Miss Liberty 1984.”

The casting of Kathleen Turner (who, in retrospect, was at the height of her powers) was a masterstroke that can be accredited to Sandler. As Russell is quoted in a 1985 interview with Allan Hunter, included in the packaging for Arrow’s lush new Blu-Ray, “I saw Kathleen in Body Heat and The Man with Two Brains. I figured that any actress who could take a custard pie and behave like that on the carpet had to have some range.” Turner’s introduction ranks as one of the most memorable introductions of a character in Russell’s lengthy filmography: seated on a throne in a blue dress, legs spread, lit in red and blue neon from the signs outside the windows behind her, clutching a bouquet, wearing a beauty queen’s tiara and a ribbon with the word LIBERTY, a man’s head between her legs while she gives an acceptance speech: “It is truly an honor to be named Miss Liberty 1984…I will always serve my country and be a shining beacon of hope for nations the world over, spreading the true spirit of freedom and liberty that is America.” We’re only a few minutes into the film, and Russell’s satirical intent is perfectly clear. Crimes of Passion would become an appropriate parting shot from the director – a goodbye to America as only Russell could deliver it. The scene is both exactly what it appears to be and, simultaneously, something quite different. After she gives him a blowjob, he asks her what her name is, and she says China Blue. He asks for her real name, and she just says, “Miss Liberty.” But there is a third, well-hidden persona, whom we will later meet: Joanna Crane, a successful businesswoman for a ladies’ sportswear brand. At night, in a sleazy motel, she will become anyone for fifty bucks – a beauty queen for this man who just broke up with his beauty queen wife, or perhaps a victim for a client who gets off on rape fantasies. Her transformations are used for comic effect. In one scene she steps into the hotel’s doors as Joanna and steps out as China Blue, like Clark Kent changing costumes in a phone booth. Later, when she has a tryst with our protagonist, she changes within seconds into a stewardess uniform, her double entendre-laced flight attendant’s speech all prepared.

Anthony Perkins as manic preacher Peter Shayne.

Also billed above the title is Anthony Perkins, seemingly intent on suggesting what an X-rated Psycho would look like. (It could be easily argued that this film is really Ken Russell’s Psycho, particularly in light of Perkins’ final scene, a tongue-in-cheek appropriation of Hitchcock. But Crimes of Passion has a lot on its mind.) Perkins plays the Reverend Peter Shayne, a demented, sweat-slathered, drug-snorting psychopath who harasses streetwalkers while draping himself in pornography. His introduction is watching a stripper in a peep show, the other customers intensely masturbating – in a typical Russell dirty joke, he shows a silver pan beneath each booth for collecting used tissues. Shayne wants to cleanse his soul, and he sees China Blue as a mirror image, someone he must deliver from sin to save himself. But his means of delivery is a silver vibrator lined with razor blades, a detail that seems to come from the world of David Cronenberg, except that it looks absurd and is utilized in the climax in the most broad and cartoonish manner. Shayne has visions of murdering sex workers with the vibrator, but this isn’t a slasher film: these are merely his fantasies – enacted, in one scene, on a blow-up doll – and we don’t really know what he intends until the finale. The 52-year-old Perkins, whose typecast career at this point mainly consisted of playing Norman Bates (Crimes of Passion was made between Psycho II and Psycho III), goes all-in. The role was the most drastic alteration from the original screenplay, since Russell had noticed the American predilection for pastors raving on TV, and believed the antagonist should be a man of the cloth. (A suitable choice, given the Catholic director’s history of films tweaking religious hypocrisy, most notably in The Devils.) But Perkins had as much to do with building the character up, providing his own pornography-covered props and reportedly living the role of Reverend Shayne off-set. In the film, Shayne stalks China Blue, delivering sexualized and profanity-riddled sermons, come-ons and condemnations entwined with confusion. Early in the film she tries to take him on as a client, but finds his fantasies to be too demanding even for her. Memorably, she sorts through his bag of sex toys – my favorite is a lash for flagellation made of red licorice, which China Blue merrily chews – before discovering the silver “Superman” vibrator.

Bobby Grady (John Laughlin) discusses his marriage in group therapy.

Amidst all this, of least interest is the audience surrogate, Bobby Grady (John Laughlin, Footloose), who is languishing in a marriage with the frigid Amy (Annie Potts, Ghostbusters). Bobby and Amy’s distressed marriage is rendered unconvincingly, because frankly Russell doesn’t seem all that interested – a shame, then, that their scenes take up so much of the film. Potts isn’t given much of depth to work with, since her character is repulsed by sex, resents her husband, and is pointlessly withering, a manufactured foil, a shrew. But when she’s forced to watch her husband become “The Human Penis” at a bizarre BBQ with friends, her bored and disgusted posture is priceless. This entire scene is Russell’s oddest send-up of suburban life, completely disconnected from authenticity: Americans as written by an extraterrestrial. Which, let’s face it, adds to the film’s outré value. But the most striking satire to intrude upon the Gradys’ married life is whatever commercial or music video that Amy is watching with dead eyes while Bobby fumbles to seduce her. “It’s a Lovely Life,” the shrieking song is called (by the film’s composer, prog-rocker Rick Wakeman of Yes). The random images send up married life and materialism. Newlyweds frolic by a swimming pool. A flower girl (Ken’s daughter Molly Russell) gapes toothlessly at a caged dove. Silverware is thrown into the pool. A skeleton holds the cage. The bride dives into the pool. Doves are placed in little coffins. Cut back to the Gradys, who don’t react to any of this Monty Python surrealism in the slightest. But Russell was capable of subtle surrealism, too, in this very unreal movie. Even Bobby gets a fantastic opening image (the first scene in the film): a straight-on head and shoulders shot as he talks to his therapy group about his sexual hang-ups. Behind him we see the other members of the therapy session, but we have to intuit that it’s a reflection in a mirror, because they’re receded, turned away. Nonetheless, they frame him perfectly. Russell’s eye for composing an arresting image was always impeccable, whatever the critics thought of his frothing content.

“It’s a Lovely Life” – Ken Russell’s surreal short film-within-a-film.

And everything in Crimes of Passion is striking to regard, bathed in neon reds and blues and purples and pinks – exactly how you would envision Ken Russell transitioning his aesthetic to the 80’s. His visuals and surrealistic digressions enliven what could otherwise be a very stagy film: Sandler’s screenplay is almost breathlessly verbose, even if it possesses its share of pithy/vulgar one-liners: “I never forget a face,” China Blue says, “especially when I’ve sat on it.” Or: “If you think you’re going to get back into my panties, forget it. There’s one asshole in there already.” Only Turner can deliver this kind of dialogue. And perhaps only Perkins could embody the crazed delirium of Reverend Shayne’s monologues; he reaches a bizarre apex with an impromptu performance of “Get Happy,” an inspiration of Russell’s. The dialogue is so hyper-stylized that it crashes elsewhere, like in the spats between Laughlin and Potts, which are genuinely awful. But Crimes of Passion is a movie that gets off on the outrageous, as though Russell were liberated post-Altered States, exhilarated to let his freak flag fly. The extreme sex scenes, particularly one in which Turner sodomizes a cop with his own night stick, place this film in the company of other erotic thrillers that explored the audience’s curiosity for the seedy or the taboo, like Paul Schrader’s Hardcore (1979), William Friedkin’s Cruising (1980), Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill (1980) and particularly Body Double (1984). As with those films, the story’s thrust (pardon the expression) is a straight-laced outsider on an adventure into a world of dangerous sex; in this case, it is Bobby, who owns a home security shop, paid to tail Joanna on suspicion of industrial espionage. He doesn’t find a thief, but he does find China Blue. The formula would become standard for the erotic thriller, perhaps reaching its purest form in Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Compare the final line of this film to that of Kubrick’s. Was Kubrick’s classier erotic adventure inspired by Crimes of Passion? It’s a funny thought, but I don’t doubt that Kubrick would have seen Russell’s film.

China Blue is hired by a wealthy couple for a three-way.

The film’s theme is perhaps best summed up in a line about sex that Bobby delivers to his wife: “It isn’t a crime to enjoy it, Amy. It’s only a crime to lie about it.” Of all the transgressive sexual acts depicted in the film (admittedly, a bit less shocking these days), the real “crime of passion” is lying: lying to oneself about one’s true desires, lying to others. The Blu-Ray contains nineteen minutes of deleted scenes, much of them exploring the relationships among Joanna/China Blue, Bobby, and Amy. By trimming them and paring the film down, the film homes in on Russell’s and Sandler’s idea of Bobby and Joanna shedding their disguises and uniting as their true selves, their sexuality a major part of that equation. The Perkins subplot could almost be irrelevant, an artificial plot device buried under shameless perversion, if it weren’t for his repeated insistence on revealing “the truth” to China Blue. He maintains that they are the same, a riddle that reaches a visual apotheosis in a climactic gag, but he’s also about stripping down layers – like Bobby, the Reverend Shayne pares down from beauty queen fantasy in a motel tryst to sassy China Blue to the very vulnerable Joanna Crane, who is barely holding it together, whatever her tough attitude and killer lines. But to sell all those layers, to make them believable as they’re shed one at a time, it could only take Kathleen Turner. As usual with a Ken Russell film, it would take a second look and a more indulgent audience to see such a shining performance behind all the walls of outrage and scandal that Russell defiantly offers like a carnival barker. But his garishness has its own beauty, and that makes Crimes of Passion another notable Ken Russell film, as well as a worthy capper to his brief Hollywood career: a portrait of America as a country desperately in need of shedding its neuroses and costumes and Puritan sexual hang-ups.