What a fascinating career director Richard Fleischer had. From the nail-biting noir The Narrow Margin (1952) to such varied projects as The Vikings (1958), Doctor Doolittle (1967), Soylent Green (1973), Mandingo (1975), and even Conan the Destroyer (1984), the director was a chameleon, always serving the material at hand. One would be hard-pressed, for example, to guess that the man behind the family-favorite Disney film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) would also orchestrate the almost nauseating tension of 10 Rillington Place (1971), nor that he would accept such a low-budget, small-profile project after the expensive Hollywood epic Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). But Fleischer, who had read the book 10 Rillington Place, eagerly accepted the offer. The true crime bestseller by Ludovic Kennedy was an account of the notorious London serial killer John Christie and his association with an innocent young couple, Timothy and Beryl Evans. In 1949 the couple were living at Christie’s squalid tenement in Notting Hill. Timothy later claimed that Christie offered to perform a cheap abortion for Beryl; the couple already had a one-year-old, Geraldine, and couldn’t afford another child. Under this guise of performing an operation, Christie raped and murdered her. Convinced by Christie that her death was accidental, Evans helped cover up the crime. Later, guilt-ridden, Evans turned himself into police, claiming he had killed his own wife, a misguided attempt to protect Christie and the illegal service he had offered to perform. He seemed to be unaware that his daughter Geraldine was also dead, still claiming she had been sent safely away, as Christie had told him would happen. Evans was convicted for murder and hanged. Christie went on to kill four more women, including his wife Ethel, before the bodies of his victims were uncovered inside 10 Rillington Place, and he was finally arrested and executed.

Beryl (Judy Geeson) goes to the pub with her husband Tim (John Hurt).

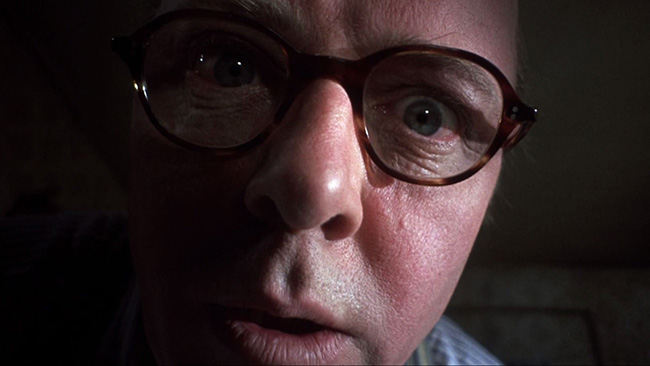

The hanging of the innocent Timothy Evans was one of the critical cases that led to the abolition of the death penalty for murder in England, Wales, and Scotland (the death penalty was suspended in 1965, then made permanent in 1969). As Richard Attenborough explained in an interview with John W. Henderson, “There was a Conservative MP…who was trying to introduce a private member’s bill into the House of Commons to reintroduce capital punishment, and we felt so passionately opposed to this that Leslie [Linder] first, and then Ludo Kennedy, got the idea of making 10 Rillington Place.” In 1971, when this film was released, the story would have been well known to the British public. This only accentuates the tension. Fleischer has crafted a resolutely non-exploitative, painstakingly detailed account of John Christie’s association with Timothy Evans and his wife Beryl, and by creeping steadily toward the inevitable, tabloid-ready outcome, the dread is almost unbearable. Yet Fleischer, who may have gotten the job because of his work on true-crime films The Boston Strangler (1968) and Compulsion (1959, about the Leopold & Loeb case), resorts to the technique of a horror film on only one brief occasion: a seconds-long extreme close-up of Christie’s sweaty face while he strangles Beryl. Only in this moment does Fleischer allow the audience to get swept up in the horror of the moment, seeing Christie from Beryl’s fast-fading POV. Everything else is matter-of-fact, staid, as subdued as Christie’s whispery voice. The film is unsettling, even ruthless in its depiction of the events, but it is also unusually restrained, particularly for a British film of this period. Hitchcock was about to begin work on the thematically similar (but fictional) Frenzy (1972), and to compare the two films at length would be fascinating. Both are deliberately drab, gritty, dreary to look at. The murders, alike in being rapes and strangulations, are shocking in part because of the contrast to working class London, where everyone is too preoccupied, eyes downcast, shuffling through the streets, to notice a killer at work until the bodies turn up. And like Hitchcock, Fleischer keeps his focus on the little details of how a crime unfolds, how it is almost undone in the act (an unexpected knock at the door as workers arrive for some remodeling; an impromptu visit from the victim’s friend, checking in), or how the killer struggles to cover up the crime (a dog digging in the yard where it shouldn’t, just as the police are searching the premises). But where Hitchcock heightens each moment – and even takes license of an R-rating to make rape more explicit – Fleischer holds back. His technique mimics Christie: quiet, unassuming, but nonetheless merciless.

Christie (Richard Attenborough) murders Beryl.

Attenborough’s performance is a wonder. Christie claimed he couldn’t raise his voice due to a gas attack while he was serving in WWI. Kennedy wrote that Christie was accustomed to feigning illness to elicit sympathy. Christie, though a violent man, was also an introvert, living in his own little world. Attenborough incorporates these details into a complex portrait. At his home in 10 Rillington Place, he moves quietly about, maintaining the order with which he’s most comfortable. He whispers orders to his wife Ethel (Pat Heywood, Romeo and Juliet), getting her out of the house for the murder he’s plotting. He offers tea to his victims. He’s reassuringly reasonable as he slips a mask over the woman’s face – treatment for bronchitis, or, in Beryl’s case, anesthesia for the operation – while turning on the gas that will render her unconscious. His elaborate explanations to first Beryl, and then (after her murder) Tim, follow a train of logic too confidently delivered for the naïve pair to dispute. He doesn’t outright offer to perform an abortion, when he learns of Beryl’s desire to have one. He resists, suggesting his moral code is against such activities; reluctantly he says he could put in a word with some medical professionals willing to perform the operation, and it’s Beryl who says that would be much too expensive. He makes her believe that she has come up with the idea of submitting herself to Christie’s care, going alone with him into his room, removing her undergarments, lying on the floor while he slips the mask onto her face. And the superb screenplay by Clive Exton (Jeeves and Wooster) reaches its queasiest heights in the scene that follows, as Christie casually manipulates both his wife (Judy Geeson, To Sir, With Love) and the illiterate Tim – played unforgettably by John Hurt (Alien) – into thinking that disposing of Beryl’s body in secret is the only possible course of action. “You know that manhole cover by the front door?” Christie says to Tim. “I’ll lay her to rest there.” Of course the audience should be screaming at Tim to wise up, but by now enough evidence has been offered of Tim’s low intelligence and limited means. He has little money, and he doesn’t want any trouble with the law. Christie ties him into a knot with ease, never raising his voice. Christie promises to take care of little Geraldine, and we’re gutted as we realize that Christie will do just that.

Christie manipulates the distraught Tim.

Even when Tim finally turns himself into the police, he can’t think straight – Christie’s spell is still cast on him, which explains his multiple conflicting confessions. In watching Hurt’s helpless performance, I couldn’t help but think of Brendan Dassey of the Netflix documentary series Making a Murderer (2015), who was similarly coerced to confess in a murder trial despite giving details that did not match up with the crime.* (Tim is convinced Beryl’s body is down the manhole. It isn’t.) Part of what makes 10 Rillington Place such a mesmerizing watch is knowing that Tim is doomed, but that he doesn’t have the faculties to properly defend himself – neither from Christie, nor the courts. Fleischer doesn’t spend a lot of time on the trial and execution of Timothy Evans, although he allows some breathing room for the audience’s outrage when Christie testifies against him. Tim is crushed by the system. His execution is filmed and edited as a conscious opposite of In Cold Blood (1967) – no lingering; Tim is done before he knows what hit him. And this, in a way, is just as powerful a condemnation of the death sentence, because we know it’s the wrong man who’s just been processed with such cold efficiency. Fleischer, again, makes his point with eloquent but devastating understatement.

* In August a judge overturned Brendan Dassey’s conviction based on the methods of obtaining his confession, though the Wisconsin attorney general has filed an appeal.