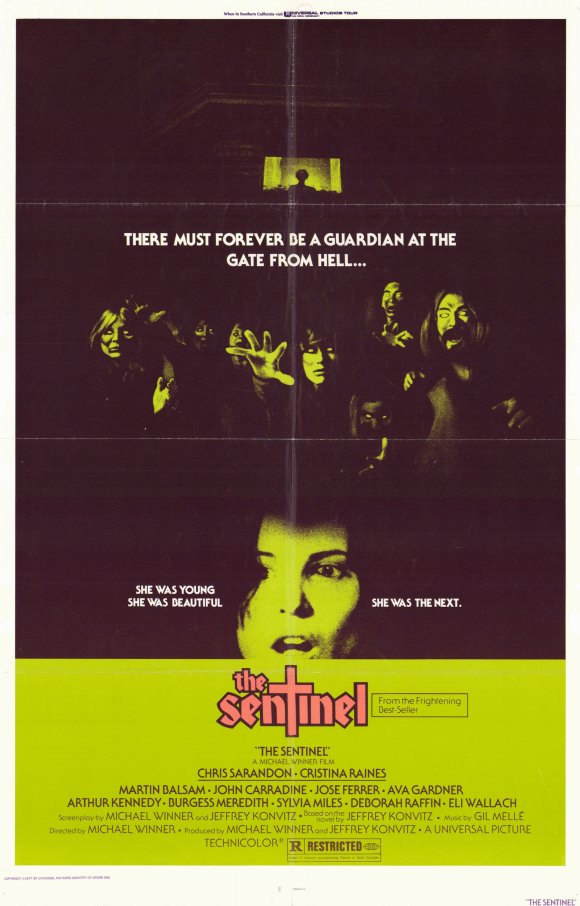

Only in the Satanic panic of the 70’s could there be a crazy, overstuffed occult thriller like The Sentinel (1977), based on a novel by Jeffrey Konvitz describing the portal to Hell as located in a New York brownstone apartment building. Konvitz co-wrote the screenplay with the film’s director, Michael Winner, who had recently made two very different features, Death Wish (1974) and Won Ton Ton: The Dog Who Saved Hollywood (1976). The story follows a fashion model, Alison Parker (Cristina Raines, The Duellists), who moves into the Hellgate brownstone after being shown the place by a landlord played by Ava Gardner. Within its walls she meets the eccentric but charming Charles Chazen (Burgess Meredith, Clash of the Titans) as well as a pair of lesbian ballerinas – one of whom (Beverly D’Angelo, National Lampoon’s Vacation) is a mute, and masturbates in front of her. She attends a crowded birthday party for a cat owned by one of Charles’ friends. But most curious of all is the resident of the top floor, a blind monk who faces out the window all day and night, and whose door remains sealed. Alison begins to faint during fashion shoots and suffers from nightmares. Her father (Fred Stuthman, Marathon Man) has recently passed away – a man whom she once caught in the middle of an orgy, which spurred her suicide attempt. Through all this trauma and memories of trauma she takes comfort in her handsome lawyer boyfriend Michael (Chris Sarandon, Fright Night), but Michael is being investigated (by Eli Wallach and Christopher Walken) under suspicion of murdering his wife. Alison’s state worsens when she learns that, apart from the monk on the top floor, she is the only occupant in the building. Michael eventually comes to believe her story, and, intrigued to learn that the building is actually owned by the Church, begins an investigation into the senile tenant at the window (John Carradine).

Chris Sarandon discovers the secret of the Sentinel.

That’s a lot of plot and a very overqualified cast; I didn’t even mention the small roles for Jeff Goldblum (who had made his film debut in Winner’s Death Wish), Jerry Orbach (Law & Order), Martin Balsam (Psycho), José Ferrer (Lawrence of Arabia), and Tom Berenger (Platoon), among other recognizable faces. Behind the scenes, the makeup effects are by Dick Smith of The Exorcist and The Godfather, and they are extremely effective in the film’s scariest setpiece, when Alison confronts her living-dead father in a dark room, and stabs his walking corpse over and over with a knife. But this is a movie assembled out of spare parts, those chiefly belonging to Rosemary’s Baby. The Satanic elderly tenants are clearly inspired by those in Polanski’s film (and Ira Levin’s book), and Alison’s mounting paranoia (is she crazy or isn’t she?) is modeled after Rosemary Woodhouse’s. She even gets a scene where she stalks around in her nightgown with a knife in her hand, a la Mia Farrow; but, this being a Michael Winner film, the nightgown is considerably more revealing here. The plot has a few too many moving parts, namely the subplot involving Michael’s past. (The payoff to that storyline just isn’t worth the effort.) Still, watching Chris Sarandon – in a gentleman moustache – breaking into a priest’s offices by night and digging up files on Carradine’s Father Halliran is pretty entertaining, even if (or especially because) the conclusions he reaches from rifling through those papers is a ludicrous leap of logic. When he opens up a wall inside the brownstone he discovers a plaque bearing the phrase from Dante’s Inferno, “Abandon hope all ye who enter here,” but he can’t get through the sentence before Carradine appears in close-up with a gaping mouth and white contact lenses. “The entrance to hell!” he says, helpfully.

Cristina Raines as Alison Parker, contemplating suicide at the urging of Burgess Meredith.

None of this is to say that The Sentinel isn’t effective. Silly, yes, but effective. Winner knows how to direct a horror movie. The aforementioned scene is staged with a silhouette creeping down the stairway past Sarandon’s profile, the surprising appearance of Carradine’s recluse. In the scene I praised where Alison confronts the corpse of her father, his arrival is through a door opening in shadows at the edge of the frame. He walks straight past her, into a closet, and faces the wall, forcing her to approach him. It’s horror staging as it should be – the logic of a nightmare. The Sentinel is stingy with its big moments, but it’s saving up for the climax, which has become one of the most notorious of 70’s exploitation cinema. When the gates of hell open and the devils crawl out, Winner decided to mix actors in makeup with real circus freaks. The alarming and uncomfortable use of human beings with deformities – representing evil, no less! – gives the climax a queasy punch to the gut that’s as much the horror of the moment as the audience’s conscience kicking in. Freaks playing devils – really? At least Tod Browning took the time to develop his circus performers as sensitive human beings in Freaks (1932) before unleashing them as agents of bloody vengeance. Nonetheless, it’s undeniable that Winner’s gall lends the memorable climax a Bosch-style tableau and a potency it might not have otherwise had. This is a drive-in movie, not sharing space with the classier likes of Rosemary’s Baby or The Exorcist. It is, indeed, the work of a carnival barker. And for horror fans, it’s a must-see.