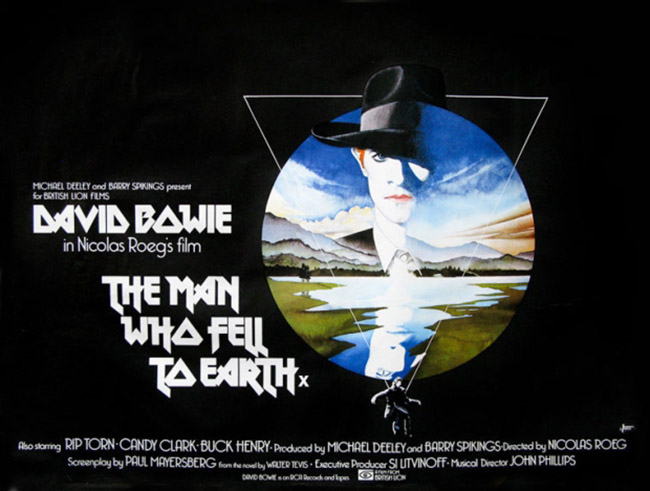

Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) is more than a film. For psychedelic SF writer Philip K. Dick, it was a source of revelation, and he fictionalized his experience watching the film for a scene in his novel of divine communication, VALIS (written in 1978, published in 1981). In the book, the movie is Valis, but it shares some similarities with Roeg’s film, including an overall temporal dissonance, creepy alien sex, and almost cryptic edits and close-ups. In Dick’s book, the film, like Roeg’s, stars a rock musician. Dick has his characters pay the actor/musician a visit to seek explanations for the theological symbolism of the strange SF flick they’ve just watched. “In a way Valis was shit,” the rock star says. “We had to make it that way, to get the distributors to pick it up. For the popcorn drive-in crowd… They expected me to sing, you know. ‘Hey, Mr. Starman! When You Droppin’ In?’ I think they were a bit disappointed, do you see.” The real “Starman” singer, David Bowie, became fixated upon the film himself. Publicity stills of Bowie as The Man Who Fell to Earth, Thomas Newton, appear as the album covers for Station to Station (1976) and Low (1977). It’s curious that a 70’s film starring David Bowie features none of his music. Bowie was eager to provide the soundtrack, but it never came together – the few tracks he provided, from his miasma of personal crises and drug addiction, were unsuitable, and after flirting with the notion of filling the soundtrack with Pink Floyd Dark Side of the Moon tracks, an eleventh hour substitute was found in John Phillips of The Mamas and the Papas. But in a way, Bowie never gave up on scoring the film; one of his final works was the stage musical Lazarus, a sequel to the Walter Tevis novel The Man Who Fell to Earth. And the Starman sang – “Lazarus” was one of his last music videos.

Alien photography.

It is certainly more than your average science fiction film: it’s a Nicolas Roeg film. Though it would be easy to group it with other pre-Star Wars SF films of great ambition and pretention of the 70’s (Silent Running, Zardoz, et al), in fact it’s nothing like them. The only proper point of comparison is other Nicolas Roeg films. It makes a natural companion piece to Roeg’s collaboration with Donald Cammell, Performance (1970), starring Mick Jagger, or his next film, Bad Timing (1980), starring Art Garfunkel. The films of Roeg are often elliptical, abstract, yet carefully constructed and edited. They rely heavily on montage; they play with time; they have a raw, sometimes graphic feeling of reality. The Man Who Fell to Earth does not look like a science fiction film; it is not about its special effects, and its high concept is really a mirror reflection on commercialism, capitalism, and the dangerous comforts of material pleasures, alcohol, and sex. That Bowie’s Thomas Newton is an extraterrestrial visitor is not even made explicit until quite late in the film, though we bring that knowledge with us to the story, and we do witness, in the opening scene, the mysterious crashing of something in a lake in New Mexico, followed by shots of Newton stumbling through the desert and down the highway. This might be the story of any genius who rises to great power, and then becomes trapped by his success. Roeg lingers in the barren New Mexico landscape, in hotels and the luxurious, Japanese styled home Newton builds on the shore of a lake to keep his lover, the simple and loving American girl Mary Lou (Candy Clark, American Graffiti). The otherworldly only happens in glimpses: a time portal through which Newton trades awed glances with early American settlers, and flashbacks to an alien world of white dunes and a humanoid, golden-eyed family in white skin-tight suits. But Roeg is more interested in Newton’s isolation. Having crash-landed to Earth, Newton now seeks a means of ending the drought on his homeworld, and returning to save his wife and children. It’s a simple premise, but in Roeg’s hands, it becomes an art film epic. Most audience members were left dazed and confused. Where were the spaceships? How to interpret the shots of aliens bouncing on trampolines against a black cosmic backdrop? Couldn’t the sex be sexier, instead of strange? What was the fixation on repulsive body horror – tweezers in the eyes, urine cascading through a woman’s panties? And why didn’t Bowie sing?

Candy Clark as Mary Lou, keeping Tommy Newton satisfied.

It’s a difficult piece of work. At two hours and nineteen minutes, it feels at least a half hour longer. You have to be in the right frame of mind. Like Roeg’s other films, it’s intellectual, coldly removed from its characters no matter how realistically (or erotically) they’re depicted. Here, that works very much in his favor, because it is the point of view of its alien protagonist, who has difficulty relating to the world on which he’s stranded. He can get an erection (whether or not those are his real genitals), but stimulation is different from emotional connection and understanding: in one key scene, he complains that the televisions that he watches endlessly are only showing, the images only surface. Screenwriter Paul Mayersberg (Croupier) is interested in the passage of time, because each moment that passes is one in which Newton’s abandoned family comes closer to death, and Roeg obliges by stretching out the scenes and cutting ahead years, sometimes decades into the future, while everyone but Newton ages. He even skips ahead an unknown span of time in the opening minutes of the film. One second, Newton is a desperate wanderer pawning a beloved ring for a mere twenty bucks; the next, he’s a coolly confident businessman meeting with Oliver Farnsworth (a charming Buck Henry) to hire him as his patent lawyer, pages and pages of formulas for technological innovations tucked under his arm. Elsewhere, middle-aged professor Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn, Men in Black) pursues co-eds, and we don’t see how his story is relevant to Newton’s, though we might guess it the moment Bryce becomes transfixed by Bruegel’s painting “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.” In the painting, a seaside village is bustling with activity, but no one seems to notice Icarus drowning in the corner. This will be the fate of Thomas Newton. And soon enough, Newton hires Bryce to work on the advanced rocket science that, he hopes, will launch him back to his home planet.

David Bowie as Thomas Jerome Newton.

He never gets there, and that’s the point. In this world of too much water, he drowns like Icarus, and no one notices. The Man Who Fell to Earth is about the fall, and though Newton enjoys a quick rise as a Steve Jobs/Elon Musk style of innovator, by participating in the capitalist, corporate system, he becomes vulnerable to it. The closest he gets to accomplishing his goal is a glitzy press tour of the launchpad. But he’s already permanently grounded: by his addiction to earthly vices, by the tranquilizing TV sets he stacks up in his home. The greatest accomplishment of Roeg’s film is his ability to express Newton’s state of frustration, exhaustion, and (true) alienation. His lover, Mary Lou, wants to connect with him, but it’s a futile effort. As he comes to realize that he has failed, he becomes increasingly self-destructive, culminating in what might be the strangest sequence in the film, a sex scene with the aging Mary Lou accompanied by the firing of guns loaded with blanks. Despite the film’s bizarre qualities, despite its aloofness, it manages real heartbreak. By the end of the story, which is not an end at all, Newton has released a pop record (“The Visitor”) but his innovations have run dry, and his contact lenses are permanently attached to his eyes, masking his true nature forever – or, rather, erasing the line between the alien and the human. Yet he can still manage a wry grin: the familiar foxy David Bowie smile. Was it any surprise that so many obits called Bowie a Man Who Fell to Earth just as often as they called him Ziggy Stardust? He lived his life as the Starman, fallen from some unknown dimension, skeletal, pale, effortlessly talented, living among mortals with a grin. Bowie never left this movie behind because he lived it.

The Man Who Fell to Earth has just been released in the U.K. in a lavish 40th anniversary Blu-Ray box set from StudioCanal, including the original, never-issued score by John Phillips.