Has there ever been a more egregious case of critics and audiences getting it wrong than that of John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982)? The film was released in the middle of a cluttered summer season, one which has become the stuff of pop culture legend. It was just a couple weeks after E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, which offered a kinder, gentler, more family-friendly alien visitor, and Spielberg’s film subsequently came to dominate the year, making the cover of Rolling Stone (“A Star is Born”) and spawning endless merchandising. Blade Runner was released the same weekend as The Thing (though its grim and intellectual approach would also isolate most viewers), and still lingering in theaters were Poltergeist, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Rocky III, Annie, and Firefox. The Thing came and went with a whimper. At least in one respect it should have attracted audiences: it was a remake of a 50’s science fiction thriller with which Baby Boomers would have been familiar (a trend that kicked off with Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers and continued through Tobe Hooper’s Invaders from Mars). It also reunited Carpenter and star Kurt Russell, who had together scored a sleeper hit with Escape from New York (1981). But The Thing was, at heart, a horror film, and a very gory one at that. Like Invasion of the Body Snatchers, it was also paranoid and downbeat. That was fine for the decade of Watergate, but by the Reagan 80’s audiences were looking for Spielbergian escapism for the whole family; even Poltergeist, with its spookshow scares, was all in good fun. Roger Ebert dismissed The Thing as “a geek show, a gross-out movie in which teenagers can dare one another to watch the screen,” expressing particular disappointment in the screenplay’s lack of characterization and the emphasis on special effects over story. He leveled the latter criticism at Blade Runner as well (though he gave it a more favorable review). Vincent Canby in the New York Times was far more scathing, calling The Thing “a foolish, depressing, overproduced movie that mixes horror with science fiction to make something that is fun as neither one thing or the other. Sometimes it looks as if it aspired to be the quintessential moron movie of the 80’s – a virtually storyless feature composed of lots of laboratory concocted special effects, with the actors used merely as props to be hacked, slashed, disemboweled and decapitated, finally to be eaten and then regurgitated as – guess what? – more laboratory-concocted special effects. There may be a metaphor in all this, but I doubt it.”

Kurt Russell as R.J. MacReady

Decades later, The Thing and Blade Runner are considered untouchable classics, the subject of countless thinkpieces and special features-laden home video reissues. The latest release of The Thing comes courtesy Scream! Factory – an exhaustive, wonderful two-disc Blu-Ray compiling prior special features and layering on even more. Among the new featurettes is an interview with Carpenter by his friend, filmmaker Mick Garris (The Stand), who was actually on set in 1982 shooting footage for the making-of documentary. At one point Garris asks Carpenter, “Whoever talks about E.T. anymore?” Carpenter doesn’t answer that, but the question turned my brain inside-out for just a moment. E.T. is a classic too, isn’t it? Doesn’t everyone love E.T.? That film was the 80’s. My family used to eat Reese’s Pieces while imitating E.T.’s croaky voice. Yet I haven’t felt the urge to revisit it since sometime in the early 90’s. And the last time I’ve heard it come up in discussion was when E.T. Atari games were rescued from an Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill. The movie is far from forgotten, but its stature has diminished somewhat, hasn’t it? Being a child of the 80’s myself, I liked the film just fine – I was even mistaken for Henry Thomas (Elliott) once as a child! – but I didn’t attach myself to that movie like I did various other movies of the era. It was never in regular rotation on my VCR. I preferred Indiana Jones and Star Wars. And, when I was old enough to watch it, The Thing gradually worked its way into my consciousness. It’s true that Carpenter’s film improves over multiple viewings (so does Blade Runner). It’s also true that critics usually have just seen a film once when they write a review, and are giving their first impressions. Ebert would sometimes confess to getting it wrong the first time. But in his review of 2011’s unnecessary but respectful prequel (also called The Thing, confusingly), Ebert’s stance didn’t seem to have changed: “The contribution by John Carpenter was to take advantage of three decades of special effects to make his creatures Awful Gooey Things from Space. That was done well in his film, and it is done with even more technical expertise here — but to what point? The more you see of a monster, the less you get.” What’s unclear is if Ebert ever took the time to rewatch Carpenter’s film. He might have found that it had magically improved over time – or that it happened to have been perfect in the first place.

The Thing prepares to conquer a microcosm: a dog kennel in an Antarctic research station.

Specifically, Ebert was comparing Carpenter’s film to the Howard Hawks production directed by Christian Nyby, The Thing from Another World (1951). I happen to also admire the original film. It has a special place in my heart: it was one of the first VHS tapes I ever owned, along with the original King Kong (1933) and It Came from Outer Space (1953), which probably says something about me. In The Thing from Another World, the alien, indeed, is hardly ever seen, wandering in other parts of the polar research station or through the subzero snows. When he does appear, he’s played by James Arness: a very humanoid form, and looking more like Karloff’s Frankenstein monster than something truly alien. I recently caught the last half of the film on TCM, and found myself absorbed in it all over again. In the rush to heap praise on Carpenter’s film, so wronged in its original release, many often neglect the qualities of the Hawks movie, which is whip-smart, funny, and builds tension effectively for a film with limited means, special effects-wise. But Hawks, in adapting John W. Campbell’s brilliant 1938 novella “Who Goes There?”, altered the premise. In Campbell’s story, the alien invader, crash landed in the Antarctic, takes on the shape, personality, and memories of its victims, essentially making it indistinguishable from the other Antarctic researchers. It’s often said that in 1951 the special effects were insufficient to adapt Campbell’s story, but this simply isn’t true – it’s a pretty cheap effect to have an actor playing an alien disguised as a human, and other films of the era did this just fine. However, having a more tangible alien menace, a monster that looks like Karloff, might have been a more commercial move in the early 50’s. Kids like their monsters, as I certainly did (and do). What is true is that the Nyby/Hawks film failed to capture the point of the story – instead it can be viewed as a classic science fiction film inspired by Campbell but not strictly adapting him. Therefore, Carpenter’s film, though it borrows the title, is less a remake than the first faithful adaptation. (The 1972 Christopher Lee/Peter Cushing/Telly Savalas-starring Horror Express is said to be rooted in the Campbell story, but it takes place on a train and adds a heaping of outré ideas that really makes it its own beast.) Carpenter, an avowed Hawks fan, does pay tribute to the original film in various ways. In Carpenter’s film, moments from the 1951 film emerge through the fate of the Norwegian team who first discover the alien: in a video recording, we see them using their bodies to trace the circular outline of the alien’s flying saucer buried in the ice, and the Thing emerges when the block of ice in which it’s encased melts. He allows fans of the original the indulgence that this might be treated as a quasi-sequel.

One part of the Thing attempts an escape.

And yes, the movie is gross, but so is Alien (1979). The gore, however, evokes a primal fear; when it comes, it is chaotic, even confusing – all hell breaks loose, and it’s terrifying. But when critics like Ebert lament the use of gore over suspense, one wonders if they were simply so overwhelmed by the FX that they didn’t realize how few and far between such moments are. Most of The Thing is suspense, nothing but actors – many of them from the theater – delivering fantastic performances: staring at one another, hurling accusations, each character coping with the fact that he doesn’t really know who or what anyone really is, and aware that at any moment the Thing might make its presence horribly known. I have seen this movie many times, but on this last viewing it had been long enough that I’d forgotten the revelations of who is the Thing, and the suspense was as taut as ever. The most celebrated sequence is a master class in balancing horror with tension, and it’s the reason that Carpenter signed on to direct the film in the first place: the blood test scene. MacReady (Russell) invents a theory that he can prove which person is the Thing by drawing a sample of their blood and trying to burn it, the idea being that each cell of the creature is a living organism and will attempt to visibly defend itself. (Though I’ve wondered why it wouldn’t do the same during the initial blood draw.) This scene is dragged out much longer than the audience expects, as those we’re sure must be the Thing prove not to be. Then, just as we’re doubting whether the blood test is an accurate method – right in the middle of a beat, right when the audience has started to relax, Carpenter gets them jumping out of their seats. What follows is an almost Lovecraftian scene of madness and horror, as MacReady’s carefully organized plan to deal with the Thing when it emerges comes to pieces immediately. The gore serves its purpose. Hell has entered this small room, and they can’t get rid of it.

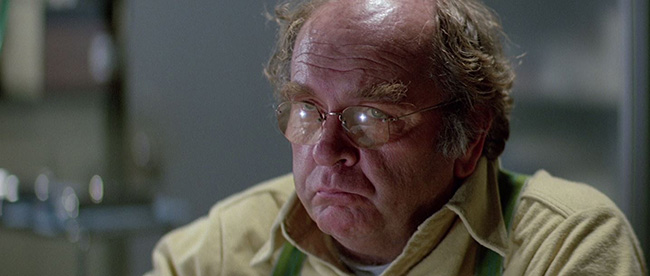

Wilford Brimley as Dr. Blair, the first to discover the Thing’s nature.

It’s always made me laugh that Carpenter didn’t bother to cast a woman in the film. The original boasted the charming Margaret Sheridan as Nikki, a cute, brainy secretary – but Carpenter, who is often playing in the key of macho, isn’t interested. It’s only recently that I realized why, and it helps answer the criticisms of Ebert and Canby that the cast is indistinguishable from one another. They’re supposed to be. It’s just a bunch of guys, which helps frustrate their attempts to find out are you really who you say you are? Carpenter actually shot scenes that better introduced the characters; the cast includes such notables as Wilford Brimley (Remo Williams: The Adventure Begins), Keith David (They Live), Richard Masur (Stephen King’s “It”), Richard Dysart (Being There), Donald Moffat (The Unbearable Lightness of Being), T.K. Carter (Runaway Train), and others. But he cut those scenes out, instead deciding that the viewer should step into this Antarctic research station as a stranger, with only suggested backstories and characterizations. As these characters begin to understand the nature of the threat, they plead to one another, I am who I say I am, just look at me, but can we believe them? We barely know them. We turn our flamethrowers toward them and keep a finger on the trigger, because how do we know that they really do have histories, or if they’re just simulacra? Carpenter’s camera has a cold, cold stare. We’re also being played in a way that might have made Hitchcock smile. The only character whom we truly trust is MacReady, because he’s the headliner, Kurt Russell. We back ourselves into his corner, staying safely behind his flamethrower. Then Carpenter pulls the rug out: MacReady vanishes. His shredded clothes are found in the snow. When he comes back, he has a wild look in his eyes, his face frosted over, refusing to explain himself and threatening the camp with dynamite. Can we trust him? By now, Carpenter has isolated the audience, asked them to question their presumptions. Famously, the film ends with the question still open: Who goes there? Who is real, and who is The Thing? I have an answer that I like, and you probably have an answer that you like, but we’ll leave it at that. The point is that the film accomplishes what it set out to do: question everything while the snow piles on, the skies get darker, and the flames start to die out. Carpenter achieved a horror masterpiece, and 1982 – with the director at the height of his powers and the full resources of Universal Studios backing him – was the perfect time to accomplish this vision. It just wasn’t the right time for audiences to accept it.