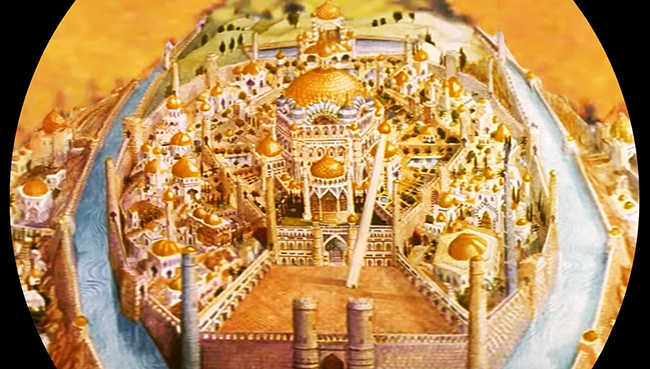

Richard Williams, the legendary Canadian-born animator who authored The Animator’s Survival Kit and won an Oscar for Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), spent almost three decades of his life trying to complete an Arabian Nights-style adventure pushing the animated form to its limit. One of its working titles was The Thief and the Cobbler, the name by which it’s now known. Countless animators worked on the project over the years, and some of the talent involved passed away during the film’s production. With the finish line finally in sight, the film was taken from him and completed by other hands. Worst of all, it was completed in ways antithetical to his intentions. Williams never wanted to make a Disney movie. But after the popularity of The Little Mermaid (1989), and with Aladdin (1992) on the cusp of release – its themes very similar to The Thief and the Cobbler – musical numbers were added to his film without his consent. The cobbler Tack, intended to be a mute tribute to silent film stars like Chaplin, Keaton, and Langdon, was now given a celebrity voice. The movie had become Disney-fied. Yet it could never be that kind of movie fully, and the body rejected the transplant. For years animation fans have traded bootlegs and tried to reconstruct Williams’ original vision. Even Roy E. Disney, always a champion for animation history inside an increasingly corporate behemoth, lobbied for its proper restoration and completion. In 2006, Garrett Gilchrist compiled the most complete version of the film, called it “The Recobbled Cut,” and uploaded it to the YouTube site The Thief Archive. A documentary about The Thief and the Cobbler, The Persistence of Vision, was released in 2012 without Williams’ participation, and awareness of the remarkable film was spread. Finally, in 2013, the original workprint – the last version of the film over which Williams had complete creative control – was screened in Los Angeles and London, with the new title The Thief and the Cobbler: A Moment in Time, words that acknowledge its incomplete state. I had the pleasure of watching this workprint last night at the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque.

The Princess Yum-Yum: sketch used in place of an unfinished animated scene.

When Williams initiated the project in 1964, it was something quite different, an adaptation of the tales of the 13th century Sufi wise man Mulla Nasrudin as collected by the 20th century Sufi author and scholar Idries Shah. (Williams illustrated Shah’s book The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin in 1966.) This film progressed far before it was abandoned in 1972 when Williams’ relationship with the Shah family, and a potential deal with Paramount, collapsed. Williams was forced to begin almost from scratch, but he persisted, working from a much simpler, original story by composer Howard Blake (to be re-written by Williams and Margaret French), retaining the Persian influence. His studio, with Ken Harris (How the Grinch Stole Christmas) as the lead animator and contributions from other noted animators including Grim Natwick (who drew Betty Boop) and Art Babbitt (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, Fantasia), continued working on the film whenever they could, but without a consistent source of financing, it was a side project, a labor of love. Voice artists carried over from the original film included Sir Anthony Quayle (Lawrence of Arabia), Vincent Price, and Donald Pleasence. The film grew elaborately and wildly in all directions, like a strange fungus overflowing from its petri dish. Williams’ intentions for the film were not modest. As he described in a 1989 interview with Thames News, “I’m just trying to do what they call a masterpiece. When you master a medium, in the old days, if you were a master painter, then you did your masterpiece…I’ve mastered this medium at last, and I’m going to do a masterpiece, I hope, if I can ever finish the thing.” Key completed sequences in the film make this clear, notably in the “war machines” climax, an excruciatingly detailed and very lengthy action scene which is perhaps what a mammoth pinball machine designed by Rube Goldberg might look like. This exquisitely animated setpiece was completed with financing from a Saudi Arabian prince in 1978. When deadlines were missed and Williams exceeded the prince’s budget by 150%, the financier backed out and the project reached yet another dead end.

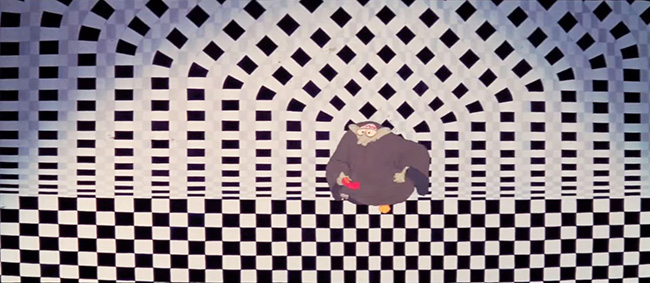

The thief and the cobbler, Tack.

Efforts were revitalized when Jake Eberts (The Name of the Rose) joined as producer, eventually injecting $10 million dollars into the production via his company Allied Filmmakers. A distribution deal was struck with Warner Bros., and a deadline was established through completion insurance. When Williams failed to meet this deadline, the film was taken away by the Completion Board Company in 1992. What he turned over was his workprint – the “Moment in Time.” It would go on to be completed under the guidance of animation producer Fred Calvert, who struggled to match Williams’ high standards of animation while adding elements to make the film more commercial, including songs, and a voice for Tack (Matthew Broderick); despite his efforts, the new additions are the most mediocre parts of the film. This 1993 cut, The Princess and the Cobbler, played in Australia and South Africa. I own the Australian pan-and-scan DVD, because for years this version was the closest to Williams’ original. Miramax acquired the film, and under Harvey Weinstein further slashed its length and released it as an afterthought in 1995, now calling it Arabian Knight. If you’ve seen it at all, this is probably the version you’ve seen. But viewing the workprint, The Thief and the Cobbler: A Moment in Time, is to witness a delightfully inventive animated film that is tantalizingly close to completion. It’s spectacular at times, but many scenes are left as pencil-drawn test footage or storyboards. It also features a temp score – often using Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Scheherazade,” naturally – and is missing some sound effects, and possibly some dialogue to better bridge scenes together. Of the incomplete sequences, most are expository or dialogue-driven, as though Williams was far more interested in the intricate slapstick moments, which contain very little dialogue at all. Only a few of the unfinished scenes, such as the collapse of a mountain shaped of hands, suggest the same level of show-stopping hyper-detail, but then again, most of the film is rendered with an absurd amount of loving attention. If Williams found a moment to be too straightforward, he would eventually find a way to complicate it, to heighten it.

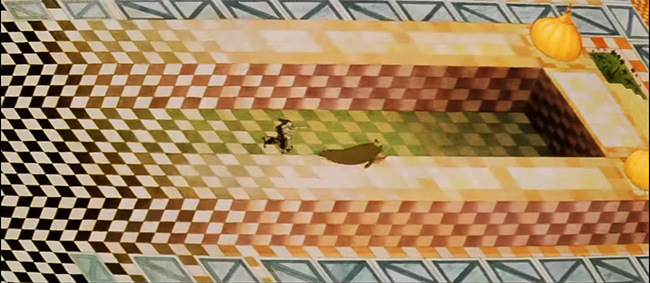

The dizzying chase through the palace, one of the film’s highlights.

What makes Thief and the Cobbler so appealing to animation fans is that Williams was pushing for the purest possible form of hand-drawn animation. Long scenes go by wordlessly with the Thief, in his efforts to steal three golden balls suspended above the city, like a kleptomaniac version of Tati’s Monsieur Hulot inserted into a Chuck Jones short. The backgrounds don’t follow Western graphical perspective, but instead pay tribute to the flattened world of ancient Persian art. Williams then warps this style into the realm of optical illusions and M.C. Escher, notably in the scene in which Tack the Cobbler chases the Thief through the black-and-white palace, swept along through endlessly spiraling stairs and continually thwarted by the baffling dimensions and disguised pitfalls of the backgrounds. Elsewhere, the Thief creeps toward a sleeping princess through what appears to be a white carpet so lush that it forms a giant hill; but he soon discovers that it’s actually the furry backs of the princess’ sleeping guardian beasts, and the floor revolts against him. And later he tries to find his way free of the grounds where a polo match is taking place, but the ball keeps following him, luring a stampede of polo players to thwack him and launch him skyward over and over again. Tack the Cobbler is an amusing creation, his mouth hidden by the tack it’s holding in place, always stitching and mending, even in his sleep. But both he and the princess (who inexplicably falls for him) are less compelling than the Thief, who sneaks along the edges of the story in pursuit of the latest prize. A clever conceit is that he’s always under the halo of buzzing flies, so that Williams can suggest his unseen presence by the placement of the flies, as with an extended scene in which the Thief tries to sneak his way up through the gutters nailed to the outside of the palace walls. The Thief has a doggedness which makes him as appealing as any of the classic Looney Tunes characters. ZigZag the Grand Vizier (Price) is also a unique creation, his long shoes uncoiling before each step like party blowers, always accompanied by his faithful vulture Phido (Pleasence). (Surely he was an inspiration for Jafar and his parrot in Aladdin.)

ZigZag (Vincent Price) and Princess Yum-Yum (Sara Crowe).

Much of the film is dazzling and funny, but the narrative and pacing are hopelessly clumsy. The unfortunate truth is that the film would have needed editing regardless, and even that wouldn’t have saved it from some of its major flaws. A journey into the desert with Tack, the Princess, and the Thief doesn’t accomplish much except to pad out the film and add a middle act. The invading army of One-Eyes, led by a barbarian whose mouth is full of sharp teeth, leads to plenty of indelible imagery reminiscent of Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards, but doesn’t demonstrate a lot of thought in the story department. The climax with the war machines is astounding; anyone would be fooled into thinking it was accomplished with computers, rather than Williams’ mathematically methodical renderings. It goes on too long, but every moment is rich with detailed gags. One could say the same thing for The Thief and the Cobbler as a whole. One could also observe that it looks like a film which had been in production since the 60’s, which would make it an odd commercial fit in the marketplace of the early 90’s. Maybe in a perfect world it would have been completed by the late 70’s, and become a reference point for animation enthusiasts for decades to come. Instead, it’s become a what-might-have-been, albeit more fully realized than, say, Jodorowsky’s Dune. The Thief and the Cobbler is, however, a “masterpiece,” if you were to use the definition outlined by Williams. None of its flaws are inherent in the animation itself. As a craftsman, Williams had perfected his craft, even if the object was evolving over three decades of his life as an artist and never properly finished. It feels particularly relevant and important in an age when almost all animation is accomplished within computers. Williams demonstrates the breadth of imagination and the degree of perfection that can be achieved entirely by hand – assuming, of course, that one has the time.