In The Spider (1931), Edmund Lowe (Dinner at Eight) portrayed Chatrand the Great, a hypnotist and magician who solves a murder. Its success led Lowe to take on the role of the similar (and similarly named) Chandu the Magician (1932), reuniting him with director William Cameron Menzies and screenwriters Barry Conners and Philip Klein. Chandu – pronounced “Shandu” – was a master of the mystic arts long before Dr. Strange, a contemporary of Mandrake the Magician and The Shadow. With his origins in a radio drama that debuted in 1931 (where he was played by Gayne Whitman), the character trained as a yogi in India before becoming a crimefighter using his powers of hypnotism, astral projection, and illusion. The formula of a white man learning the mystical secrets of the Orient and returning to the West to battle evildoers continues into contemporary superheroes, including not just the Benedict Cumberbatch incarnation of Dr. Strange (2016) but also the new Netflix series Iron Fist (2017); despite their efforts to modernize the characters (and I loved Dr. Strange), both have taken criticism for their pulp-tradition political incorrectness. It’s easier to appreciate these naïve genre clichés when watching Chandu, because at the time the concepts were still somewhat fresh. In the early 30’s, white audience members could become lost in the fantasy of traveling to the far East and uncovering occult mystery because the exotic Orient – in this case, India – seemed like an impossibly distant place and a mysterious one. Of course, part and parcel was the uncomfortable colonialist fantasy of a white man becoming the master of what’s implied to be a less civilized people. The 1930’s were full of Chandus, but the modern viewer might be relieved to know that Chandu the Magician doesn’t contain the kind of overt racism of many of its contemporaries. For example, the Sax Rohmer adaptation The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), with Boris Karloff and Myrna Loy, is far more racist, although that film is worth watching for its impressive effects, delicious performances by the villainous leads, and campy dialogue. Karloff, as it’s well known, had a richer and more rewarding career than his one-time rival Lugosi. But at least in this pulp match-up, Lugosi comes through the winner. I am not at all embarrassed to state that Chandu is one of my favorite films of the 1930’s.

Bela Lugosi as Roxor, beside his stolen Death Ray.

Lugosi plays the Egyptian Roxor, an evil mastermind whose latest plot is to steal a “Death Ray” (yes, it’s called that) from a scientist, Robert Regent (Henry B. Walthall, Strange Interlude), who, I suppose, only wanted to use his Death Ray for good. But even with the Death Ray in hand Roxor can’t operate it, and demanding that Robert reveal its secret he resorts to kidnapping his daughter, Betty Lou (June Vlasek, aka June Lang, Ali Baba Goes to Town). Lugosi is a treat here, at the peak of his stardom following Dracula (1931); in the same year as Chandu, he would appear in the horror classics White Zombie, Murders in the Rue Morgue, and Island of Lost Souls – not a bad run at all. Wearing all black right up to his turban, he has a strangely svelte, athletic appearance, capitalizing on the exotic sex appeal that led him to first being cast as Dracula on the stage. Late in the film he fantasizes about the grand destruction he’ll bring about with his new device, and an extreme close-up of his grinning face melts into images of Paris being zapped and obliterated. With his thick Hungarian accent he exults,

At last I am king of all! That lever is my scepter. London, New York, Imperial Rome, I can blast them all into a heap of smoking ruins. Cities of the world shall perish. All that lives shall know me as master and tremble at my words. Paris, city of fools! Proud of their Napoleon. What will they think when they feel the power of Roxor?

Princess Nadji (Irene Ware) and Frank Chandler, aka Chandu (Edmund Lowe), consult the crystal ball.

Lugosi is a damn sight better than Lowe, whose Chandu (real name: Frank Chandler) comes across as too condescending to be truly charismatic. He’s best when showing off his supernatural powers. Chandu is introduced graduating from what might as well be Yogi Academy. To pass his finals, he first levitates a rope, which one of the other yogis climbs into another dimension – the rope follows. Then he astral projects, and finally he walks across flames. Having proven his abilities, he’s encouraged to go forth and destroy evil wherever it lies. He enters the Regent residence in a splendidly atmospheric scene: down a long corridor a door opens of its own volition, and his silhouette can be seen; then darkness rolls over, and when light is cast back into the passage, he is standing facing the audience in full mystic regalia. Lowe does appreciably better when he’s in disguise as an elderly beggar, infiltrating a walled Egyptian city by creating a doppelgänger that vanishes after luring its victims astray (in one instance, leaving a shell of clothing that drops to the ground). Chandu is aided in his adventures by the two young Regents, Betty Lou and the Boy Scout-ish Bobby (Michael Stuart), as well as the beautiful Princess Nadji (Irene Ware, The Raven) and the alcoholic comic relief, Miggles (character actor Herbert Mundin, The Adventures of Robin Hood). To keep Miggles from drink, Chandu hypnotizes him into seeing a miniature version of himself that constantly warns him away from alcohol. In an odd twist, at the end of the film it’s the mini-Miggles that wants a drink. Most of these characters are imported from the radio drama, and frankly it’s a relief that the film wastes no time introducing them, assuming a bit of audience familiarity. Even after the film has ended, I’m still not sure what role Princess Nadji served, except to be Chandu’s Girl Friday, someone accustomed to the occult arts; she’s a more appropriate romantic match than the too-innocent and too-teenaged Betty Lou (Vlasek is given a scantily clad, envelope-pushing white slavery scene which is very Pre-Code). Everything moves so fast that you don’t have time to wonder over who’s doing what or why. It’s like a sixteen-part serial compressed into a crazy seventy minutes, and it’s a delirious pulpy delight.

Betty Lou (June Lang/Vlasek) and Dorothy Regent (Virginia Hammond).

Credit for the constant invention must go to co-director Menzies, the famed art director of films like The Thief of Bagdad (1924) and production designer of Gone with the Wind (1939), who had an impressive directing career, including Things to Come (1936), Invaders from Mars (1953), and the underrated Gothic chiller The Maze (1953). Menzies would become a Hollywood legend, and in the early 30’s he had already developed a substantial reputation as a man who could provide eye-popping visuals. Standout moments in Chandu include a point-of-view plunge into a miniature representing an ancient Egyptian temple, dashing down the snaking hallways; armed thugs emerging from sarcophagi whose lids mechanically lower before Chandu turns their rifles into snakes like a modern Moses; the montage of global destruction, including a dramatic flooding, as envisioned by Roxor; Chandu, sealed in a coffin, working a Houdini escape after it’s dropped to the bottom of a subterranean river; and the clever climax featuring a slowly overheating Death Ray. If only all 30’s pulp serials could look this spectacular. (Many scenes, in particular those inside the booby-trapped temple, seem to have been an inspiration for Raiders of the Lost Ark.) Menzies is joined by his French co-director Marcel Varnel, whose specialty was comedy; Varnel was given most of the dialogue scenes, which are the weaker parts of the film. Luckily, no one sits still in this movie for very long.

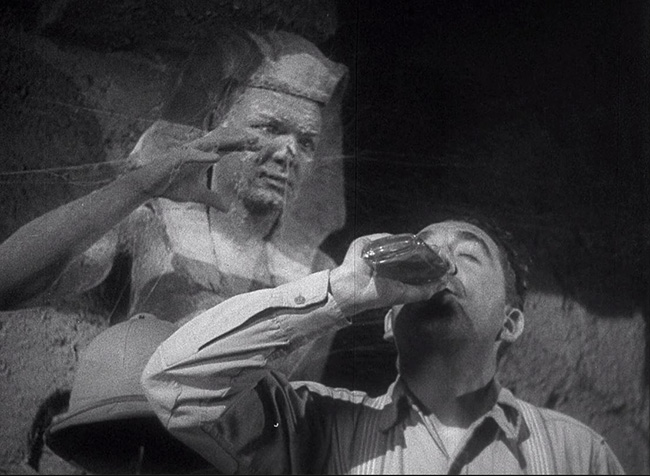

A living statue stalks Miggles (Herbert Mundin) inside the Egyptian temple.

Following Chandu the Magician was the twelve-chapter serial The Return of Chandu (1934). This time, Lugosi graduated to the good guy, playing Chandu opposite Maria Alba (Mr. Robinson Crusoe) as Princess Nadji. They reunited for a follow-up serial, Chandu on the Magic Island (1935). Meanwhile Chandu the Magician, while finding fans in such genre aficionados as Ray Harryhausen, disappeared into obscurity as the decades passed, perhaps assumed to be one of the lesser versions of Lugosi schlock. It isn’t. In recent years there’s been a reappraisal, aided by a DVD release in 2008 as part of the box set Fox Horror Classics Vol. 2. Last year Kino Lorber, continuing their excellent work upgrading unlikely films to high definition, released Chandu on Blu-Ray. It still looks its age; it’s a scratchy old film (as my screenshots from the Blu-Ray attest), but with its lovingly rendered film grain comes the warmth of yesteryear matinee thrills, a rollercoaster ride chock full of inventive special effects and nonstop boyhood imagination. It is the height of its modest genre.