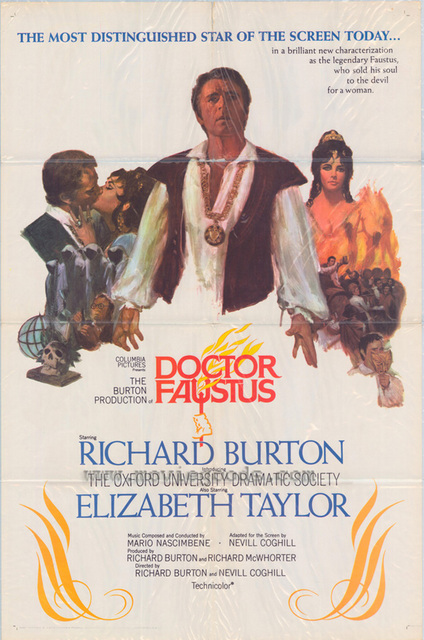

Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) is best known for his plays The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus and Edward II, and conspiracy theorists have long postulated that he faked his premature death (he was stabbed just above the eye during a brawl) and continued writing under the pseudonym of William Shakespeare. This, of course, is ridiculous, and there is a tremendous disparity between the starch-stiffness of Doctor Faustus, with its “over-solitary” protagonist who mostly speaks to phantoms and the walls, and, say, Macbeth, in which the Faustian bargain of its title character, in the form of learning of his own destiny by the three witches and then proceeding to make it happen at all costs, has more philosophical and narrative complexity, not to mention an impressive plot structure with a richer supporting cast. Which is to say, if this were a gymnastics competition, Marlowe’s Faustus would please the judges, but Shakespeare is performing at a great degree of difficulty and aiming for the perfect 10. Nonetheless, language-focused scholars continue to bring Marlowe into the Shakespeare conversation, to the extent that he was recently credited as co-author of the Henry VI plays by Oxford University Press. This is a more reasonable assertion, although it still feels like a parlor game that doesn’t trust history to know its own facts. But there is no doubting that Doctor Faustus is Marlowe’s alone. He wrote the play sometime in the late 16th century, and it was performed many times before being published posthumously in 1604 and then, with significant differences, in 1616. The story, of the brilliant scholar Dr. Faustus who signs his soul over to Lucifer for a chance to expand his knowledge and mastery of the world, was adapted from an anonymous chapbook published in 1587, Historia von D. Johann Fausten, itself the latest in a long line of tales of men striking deals with the Devil. Later it would be adapted into Goethe’s play Faust (1806-1831, though Goethe had begun working on it much earlier), and further significant incarnations of the tale would come in the form of classical music (Schubert, Schumann, and Liszt), opera (Charles Gounod), and, of course, cinema. The best film adaptation of the tale is F.W. Murnau’s 1926 masterpiece Faust, a pinnacle of German Expressionism and filled with fantastic images and black comedy. Forgotten among the many iterations is the Richard Burton/Elizabeth Taylor Doctor Faustus (1967), though there may be good reasons why no one ever mentions it.

Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) is best known for his plays The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus and Edward II, and conspiracy theorists have long postulated that he faked his premature death (he was stabbed just above the eye during a brawl) and continued writing under the pseudonym of William Shakespeare. This, of course, is ridiculous, and there is a tremendous disparity between the starch-stiffness of Doctor Faustus, with its “over-solitary” protagonist who mostly speaks to phantoms and the walls, and, say, Macbeth, in which the Faustian bargain of its title character, in the form of learning of his own destiny by the three witches and then proceeding to make it happen at all costs, has more philosophical and narrative complexity, not to mention an impressive plot structure with a richer supporting cast. Which is to say, if this were a gymnastics competition, Marlowe’s Faustus would please the judges, but Shakespeare is performing at a great degree of difficulty and aiming for the perfect 10. Nonetheless, language-focused scholars continue to bring Marlowe into the Shakespeare conversation, to the extent that he was recently credited as co-author of the Henry VI plays by Oxford University Press. This is a more reasonable assertion, although it still feels like a parlor game that doesn’t trust history to know its own facts. But there is no doubting that Doctor Faustus is Marlowe’s alone. He wrote the play sometime in the late 16th century, and it was performed many times before being published posthumously in 1604 and then, with significant differences, in 1616. The story, of the brilliant scholar Dr. Faustus who signs his soul over to Lucifer for a chance to expand his knowledge and mastery of the world, was adapted from an anonymous chapbook published in 1587, Historia von D. Johann Fausten, itself the latest in a long line of tales of men striking deals with the Devil. Later it would be adapted into Goethe’s play Faust (1806-1831, though Goethe had begun working on it much earlier), and further significant incarnations of the tale would come in the form of classical music (Schubert, Schumann, and Liszt), opera (Charles Gounod), and, of course, cinema. The best film adaptation of the tale is F.W. Murnau’s 1926 masterpiece Faust, a pinnacle of German Expressionism and filled with fantastic images and black comedy. Forgotten among the many iterations is the Richard Burton/Elizabeth Taylor Doctor Faustus (1967), though there may be good reasons why no one ever mentions it.

Richard Burton as Dr. Faustus.

Burton and Taylor had appeared in a stage production of Doctor Faustus the previous year for the Oxford Playhouse, benefiting the Oxford University Dramatic Society. Despite mixed to negative reviews, the star power involved led to this filmed record. Burton is credited as co-director with his former English professor, Nevill Coghill, making this a unique vanity project for the actor. He plays Faustus, and Taylor, who has no dialogue, is his muse, Helen of Troy. The same year, Burton also starred with Taylor in Zeffirelli’s adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew (1967) to better notices, and the couple had just made an indelible mark with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966). However, the most famous couple in Hollywood history, the mega-stars of the mammoth Cleopatra (1963), were on the cusp of a rapid decline. The late, great Robert Osborne, in one of his last columns for TCM’s Now Playing (March 2017), wrote:

Much newspaper space was devoted to Elizabeth’s love of diamonds and Richard’s signing up for less and less sterling movie roles to allow him the ability to buy bigger and bigger jewels for his wife (including an elephantine 69.42 carat diamond he bought for her in 1969 at Cartier’s). His fellow actor and close friend Laurence Olivier, well aware that Burton and his career were both spiraling out of control, eventually sent Richard B. a one-line telegram that said, in essence, “Do you want to be remembered as a great actor or a household name?” Burton sent a one-word reply: “Both.”

But one thing is clear: Doctor Faustus was never intended to be a blockbuster; at least, it would have been naïve to ever think that such a literary production could enjoy popular success. He was respecting his theater roots and bringing his beloved Taylor along with him.

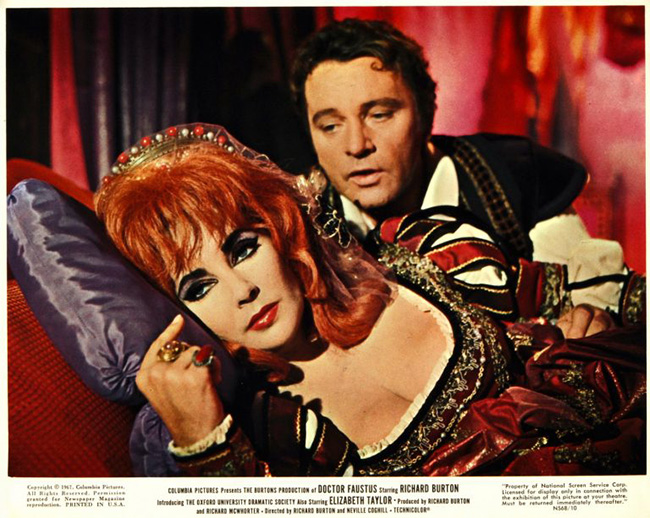

Elizabeth Taylor as Helen.

To the credit of directors Burton and Coghill, Doctor Faustus has a suitably occult Gothic feel, and it looks for all the world like a lost entry in the Roger Corman-directed Poe series. Colors are bright while retaining a trapped-in-Hell aesthetic. A skeleton hangs next to Faustus as he delivers his soliloquies in his cave-like study, and he decorates a skull on his desk with the black laurel he received from his university. As he is swept along on his long, strange trip, he encounters the 7 Deadly Sins hidden behind masks (Greed is suspended inside a small cage, counting coins), and at one point a number of monks disappear from their cloaks, leaving their hoods vacant, like an assortment of Grim Reapers. Mephistophilis [sic], played by Andreas Teuber and carried over from the stage production, looks like The Seventh Seal‘s Death, and has an impressively forlorn aspect, casually describing the nature of fallen angels and his master Lucifer (David McIntosh, also from the play). On two occasions Burton wanders into a starfield, like the walls falling away for “The Galaxy Song” in Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983) – though to a modern viewer it will be a reminder that a singing and dancing Eric Idle could only enliven this movie. Nude or semi-nude women are offered to Faustus for his pleasure, but invariably they turn into ugly hags. And as Faustus descends into Hell in the final scenes, the screaming damned are flogged all around him (though Coffin Joe has done this better).

Lobby card.

Every once in a while Taylor wanders in, accompanied by five notes which are supposed to sound ethereal, but are like fingernails on a chalkboard. She is filmed in soft focus and struts before Burton while he gapes in lust, then she disappears. By the second or third time this happens, the film changes from tragedy to comedy. “Was this the face that launched a thousand ships?” Dr. Faustus famously asks, to which the natural response is, “No, that’s your wife, Elizabeth Taylor.” Her most impressive makeup – or, at least, her most memorable – is a thick coat of silver paint and a wig made of silver paper curls. In the finale, she becomes a Medusa to drag the good doctor to Hell. But her “glamorous” presentation foreshadows the perfume commercials that would become her prime acting opportunities in later decades. She is displayed like soft-focus divinity incarnate, but never given a single line of dialogue, all she can do is walk some invisible catwalk in her admirer’s library. It’s just one piece of the delusion that fuels Burton’s Doctor Faustus. Though Marlowe’s play is a classic, it contains no real narrative drive; what has endured is its intriguing central idea. Murnau, at least, found quite a bit for his Faust to do while conducting his dealings with Satan. Burton and Coghill alter and cut the play, but they don’t feel compelled to help with its story. For 93 minutes, Burton walks back and forth through the frame delivering his Marlowe passionately, and all that ever happens is Taylor, materializing and de-materializing in her various gowns. Perhaps I’m neglecting the epic battle scene which interrupts the Pride sequence – except this is all borrowed stock footage. A more liberal adaptation of the source would have been welcome, because despite all the 60’s Gothic piled mustily into the frame, to make this one-man-(and-his-woman)-show truly cinematic would require a great deal of visual razzmatazz, something more like F.W. Murnau’s silent film. Instead, it’s like spending an hour and a half locked in a cobwebbed cellar growing nauseous on vats of old perfume.