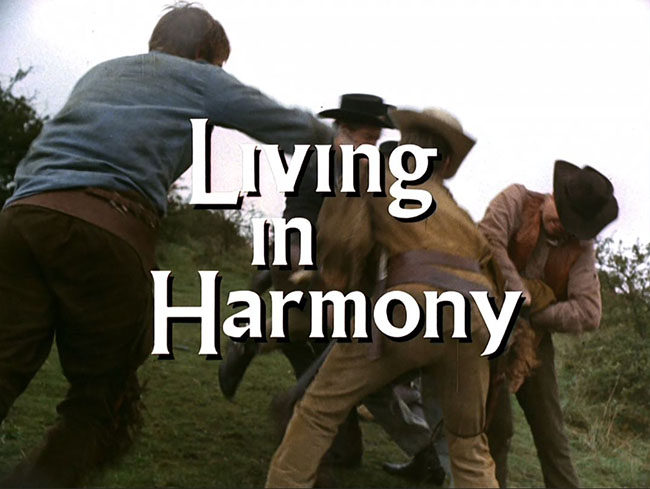

LIVING IN HARMONY First UK Broadcast: December 29, 1967 [episode #14 in transmission order] | Written by David Tomblin | Directed by David Tomblin

SYNOPSIS

In the Old West, a Sheriff (Patrick McGoohan) turns in his badge to a Marshal seated at a desk. He rides off on his horse, but finds himself accosted by men who drag him to a town called Harmony. The town is ruled by “the Judge” (David Bauer, Diamonds Are Forever), who operates out of the local saloon. The Judge asks the nameless stranger to act as the town’s new Sheriff, but he refuses, only wishing to leave. The Judge asks him why he quit his job as Sheriff in the first place, but the stranger won’t answer. He meets Kathy Johnson (Valerie French), a showgirl at the saloon, and the Kid (Alexis Kanner), the disturbed, childlike gunslinger obsessed with her. While the stranger is held in “protective custody” in the local jail, Kathy’s brother is hanged. She decides to help the stranger escape, but after he steals a horse and rides north, he’s seized by men from Harmony and dragged back. Kathy is put on trial inside the saloon for helping the stranger escape, but he negotiates her pardon by agreeing to become Sheriff of Harmony, which pleases the Judge. With the Kid acting more violent and unpredictable, the townspeople of Harmony urge their new Sheriff to take up the gun and starting delivering justice. But it’s not until the Kid strangles Kathy to death that the stranger challenges him to a shootout, killing him as well as other men serving the Judge. The Judge finally shoots the stranger, and with his death, the illusion bursts: he’s No.6, wearing a headset in a Wild West set occupied by cardboard cutouts. Just over the hill is the Village. He enters the Green Dome and discovers the cast waiting for him: the Judge is No.2, the Kid is No.8, and Kathy – still alive – is No.22. The experiment was conducted using hallucinatory drugs. Shaken, No.6 leaves without saying a word. Kathy begins to cry. Later that night, she visits the saloon set, still dwelling on her time in the world of Harmony. No.8 is there, acting as disturbed as the Kid, and he strangles her. No.6 is also still lingering in Harmony, and he rushes to the scene. No.8 flings himself from the upstairs landing, breaking his neck, and No.2 arrives, shattered at what he sees. The illusion has overtaken reality for these players.

Patrick McGoohan as the nameless prisoner of Harmony.

OBSERVATIONS

This is a marvelous episode, original, raw, and daring. It was one of the last produced, right after “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling” and just before “The Girl Who Was Death” – three episodes which depart the familiar Village scenery (for various reasons). But “Living in Harmony” stays on-point to the themes of The Prisoner, even while it subverts the viewer’s expectations. Connections are teased: though the title The Prisoner never appears on-screen, leaving the viewer to wonder if they’re watching the right show, the episode nonetheless opens with McGoohan tendering his resignation to a man behind a desk, traveling away, and getting taken against his will to a village dominated by an authority who won’t let him escape. The insistence that he don the Sheriff badge vaguely recalls “Free for All.” The mockery of a trial to which Kathy is subjected calls back to “Dance of the Dead.” And the Judge asks the stranger pointedly why he resigned. Ian Rakoff and series producer David Tomblin conceived of the story after McGoohan said that he always wanted to do a Western. With Westerns being an American genre (successfully appropriated in the 60’s by Italy), “Living in Harmony” was also daring – though not entirely groundbreaking – for attempting a British Western. Contributing to the American feel is the casting of David Bauer, a blacklisted American expat, as The Judge/No.2.

Kathy (Valerie French) and the Kid (Alexis Kanner).

“Living in Harmony” would feel gimmicky if it were only a standard Prisoner in the Wild West, but there’s more on its mind. Unlike any other episode in the series, this is a story about violence. Harmony is a town living under the pall of violence, and the ex-Sheriff, who tries to maintain a peaceful stance, is pressured to use his weapon in response – but, as we see, it comes at a heavy cost. The timeliness was spot on: it first aired in the U.K. at the end of 1967, on the cusp of the most violent year of the decade. During the initial 1968 Prisoner run in the States, this episode didn’t make it to air. Though CBS stated it was because of the explicit reference to hallucinogens, the true reason appears to have been its controversial portrayal of pacifism during the height of the Vietnam War (1968 was the year of the Tet Offensive), and a potential anti-American interpretation of the events in the story. McGoohan’s character, like John Drake in Danger Man, refuses to use a firearm. But eventually his rage at Kathy’s murder compels him to give into his violent impulses. For evidence of McGoohan’s power as an actor, look no further than the scene in which he finally picks up his gun. He walks into the sheriff’s office with his gun hand in a paralytic claw shape as he drapes his jacket on the desk and washes his hands. Then he reaches for the weapon and we realize his muscles were craving it; the handle fits easily into his taut grip. He satisfies his revenge by winning his quickdraw against the Kid, but it leads to a massacre of a shootout. McGoohan gives us the satisfying Western finale the genre demands, but in “Living in Harmony” it’s also a vision of Hell. This is in alignment with the Anti-Westerns or Revisionist Westerns which began after WWII and continued through the work of Sam Peckinpah and into contemporary film. With its reveal that this has all been a carefully manipulated drug trip, the episode joins the more rare subgenre of the Acid Western.

Tempted by the gun.

Writer Ian Rakoff drew from his first-hand experiences of apartheid while growing up in South Africa in the 40’s and 50’s, as well as his personal experiences as part of a leftist group during that period. Rakoff later claimed he wrote most of the script and that producer Tomblin took his name off unjustly. Regardless of who wrote what, Tomblin does an exceptional job of directing, lending each moment a tense, anything-can-happen feeling only matched in this series by McGoohan’s direction of the harrowing “Once Upon a Time.” A shot of McGoohan burying the showgirl in a cemetery, his stark silhouette standing beside those of the crosses on the hill, is particularly evocative, almost Expressionistic. Though the story is slow to build, the final ten minutes and its quickly unraveling events and revelations make for mesmerizing horror. One can excuse little missteps, such as No.22 getting strangled to death but somehow managing to deliver one last line to No.6., or the fact that No.8’s devolution into the Kid is a little too fast. This is really a feature film’s worth of plot packed into an hour, which provides some weaknesses but also a lot of strengths. Contributing to the episode’s power are two fantastic performances, McGoohan’s and Alexis Kanner’s. Kanner’s man-child the Kid, resembling a Clockwork Orange droog in his top hat and longjohns, is one of the scariest villains of 60’s television. He also gets an amazing death scene. He spins his gun back into its holster with his usual robotic movements, stares passively forward, and then, seconds later, falls over dead. Kanner’s so good it’s no wonder that McGoohan brought him right back for “The Girl Who Was Death” and “Fall Out,” and later reunited with him in the Kanner-directed Kings and Desperate Men (1981). The two actors practiced their quickdraw skills on set as a competition, but one of the great pleasures of this episode is watching them compete as first-class actors.

No.6 uncovers the deception.

The title “Living in Harmony” underlines the impossibility of the nameless stranger to live in harmony with his community. He is constrained to take the role forced upon him (Sheriff) and act as expected (with guns blazing). But by doing this, he destroys both himself and the community. It’s the Prisoner’s relationship to the Village through a glass darkly, and reflecting the greatest theme of the series. The world around the individual is built to crush and extinguish individuality in the name of conformism. “Living in Harmony” is cynical, but the cynicism is part of the series as a whole: consider the program’s original, deleted end credits tag, in which the Earth spins toward the viewer until it goes “POP.” McGoohan’s vision of civilization was one structured for its own destruction as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

SEQUENCE

The Kid is revealed to be No.8, the latest to carry the number after “Checkmate,” “The Chimes of Big Ben,” and “It’s Your Funeral.” Because No.8 dies in the climax, it would probably make logical sense to place this before “It’s Your Funeral,” which features a No.8 who’s just a regular Village observer who might have inherited the number from Kanner’s character. But for our sequencing, we’re almost out of episodes and quickly running out of room; there’s less space to maneuver. With my desire to use “It’s Your Funeral” to separate the non-Village episodes “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling” and “Living in Harmony”…here we are. You’ll just have to assume that the No.8 in “It’s Your Funeral” was either transferred out or died in a horrible Village taxi accident.

No.8 (Kanner) and No.22 (French) confront the repercussions of their experiment.

METHODOLOGY

This is a very 60’s version of virtual reality, involving headsets, hallucinogens, and cardboard cutouts on a Wild West movie set. Don’t ask for the details on how it worked. The big revelation is intended to be surreal, stylistically invoking the drug trip explanation. This was a show actively engaged in reflecting its times.

ALBERT ELMS

When No.6 emerges from his hallucination and discovers that Harmony is nothing but a set with props, in siren-like bursts through the soundtrack we hear the familiar sound of the Village marching band. At first it’s so brief we’re not quite sure we heard it, then it recurs, and recurs, and finally No.6 looks down a slope and see the Village as we know it. The show has reset itself, the Western movie completely dissolved like waking from a dream. It’s a fantastic moment and draws attention to the imaginative talents of Albert Elms, the series composer, arranger, and musical conductor.

Elms was born in Newington, Kent, in 1920, and played with the Royal Marines Band Service (RMBS) from 1934 to 1949 before working for the music publisher Francis, Day, and Hunter Ltd. He went on to become a prolific composer for television, working on series at both ITC (The Adventures of Robin Hood, Man in a Suitcase) and the BBC (Thorndyke). For The Prisoner, his music embraced McGoohan’s vision of the series as a mid-point between spy thriller and psychedelic pop art. While his fighting cue was jazz mayhem, at other times the music has a woozy, careening quality, like a syringe shot of some terrible Village concoction. Occasionally “Pop Goes the Weasel” creeps in, emphasizing the almost mockingly bizarre nature of the Village and its relationship to the tormented No.6. Elms passed away in 2009 at age 89. His music for The Prisoner has been released on CD, beside the memorable main theme by Ron Grainer.

David Bauer as the Judge.

THE WARDERS

Both of David Bauer’s characters – the Judge and No.2 – see themselves as dealers at a game where the house always wins. Just as the Judge corners the stranger into predetermined actions, No.2 orchestrates the larger story of “Living in Harmony.” And both characters lose control disastrously, underestimating the impact on the lives of the players. For No.2, he sees his players confuse the drug-fueled dream with reality, with No.8 collapsing into hysteria and murder, lost in the role he portrayed.

FISTICUFFS

The Prisoner is beaten up quite often in this one, but none more memorably than the beating he takes right behind the opening title ironically proclaiming “Living in Harmony.”

WIN OR LOSE?

After a number of wins, this is a loss for No.6. The climax measures the damage wrought by his decision to finally carry a gun. The illusory gunshot blast to the face from No.2 signals his final defeat, as he wakes, nearly broken, from his “trip” to Harmony. Yet this is no victory for No.2 either, as he watches the fallout unfold.

Everyone loses.

QUOTES

Kathy: Regulars get the first one on the house.

Prisoner: I’m not regular.Judge: He’s good. Sensitive. But one of the best.

Harmony resident: Well, stranger? Fancy living in Harmony?

Judge: You’ll find it’s a rough town without a gun.

UP NEXT: A CHANGE OF MIND