FALL OUT First UK Broadcast: February 2, 1968 [episode #17 in transmission order] | Written by Patrick McGoohan | Directed by Patrick McGoohan

SYNOPSIS

The episode opens not with the standard opening credits but a recap featuring scenes from “Once Upon a Time,” culminating with the death of No.2 (Leo McKern) during the extreme program called “Degree Absolute.” After the title credit “Fall Out” is projected over an aerial sweep of the Village, we return to No.6, the Butler (Angelo Muscat), and the Supervisor (Peter Swanwick) as they walk down the hallway out of the Embryo Room, then descend by the same lifts-in-the-floor that we typically see in No.2’s chamber in the Green Dome. Doors part and No.6 walks into a dressing room in which the only outfit is a black jacket draped over a mannequin in the Prisoner’s image. “We thought you’d be happier as yourself,” the Supervisor says. No.6 is then led through a tunnel of jukeboxes while the Beatles’ “All You Need is Love” plays. An ancient-looking door lies at the end of the tunnel, and the Supervisor unlocks it with a key. They enter a large cavern which contains: a raised podium at which the President (Kenneth Griffith) awaits wearing a judge’s wig; an empty throne on a dais; the “Assembly,” rows of seated figures wearing white robes and black and white Greek comedy/tragedy masks; a surgery unit with an operating table and medical equipment under square scaffolding; many armed guards in white helmets; a wall of computers; more masked figures seated at a table; the familiar observers’ see-saw from the Control Room; tubes in the floor hissing steam with one man bound there on a pole; and a missile-shaped cylinder with a single glowing eye and the number “1.” The Supervisor dons one of the tragi-comedy masks. Then the President announces:

This session is called in a matter of democratic crisis. And we are here gathered to resolve the question of revolt. We desire that these proceedings be conducted in a civilized manner, but remind ourselves that humanity is not humanized without force, and that errant children must sometimes be brought to boot by a smack on their backside!

The President (Kenneth Griffith).

The Prisoner is told that he has survived “the ultimate test” and that “he must no longer be referred to as a number of any kind. He has gloriously vindicated the right to be individual.” He is offered the “Chair of Honor” – the empty throne – which he accepts. Then the President asks for the Prisoner’s indulgence while they conduct a ceremony for the “transfer of ultimate power.” The President requests that No.2 be resuscitated, and the surgeons go to work after his body is brought out of the mobile cage from “Once Upon a Time” (which has been lowered into the cave). While this is occurring, the President resumes his discussion of “revolt,” intending to look at three different examples. First he turns his attention to the young man tied to the pole in the floor tube, No.48 (Alexis Kanner).

Youth with its enthusiasms, which rebels against any accepted norm – because it must and we sympathize! It may wear flowers in its hair and bells on its toes, but when the common good is threatened, when the function of society is endangered, such revolt must cease. It is non-productive and must be abolished.

No.48, a hippie, begins singing “Dem Bones” while running about the cavern, working the Assembly up and messing with the computer controls. Ultimately he’s restrained and found guilty by the Assembly. Next No.2, resurrected and freshly shaven, is brought forward. He tries to get the Butler to follow him, but the Butler now serves the Prisoner. “New allegiances!” says No.2. “Such is the price of fame. And failure.” The Prisoner asks No.2 if he’s ever met No.1, and No.2 scoffs. He looks at the rocket with the “1” painted on it and says, “Shall I give him a stare?” – looking directly into its unblinking electronic eye. The President accuses him of transgression. He too is restrained and the Prisoner asks that he be held in the “place of sentence” until after his inauguration. The President describes No.2 as belonging to the second kind of revolt, one which “bites the hand that feeds him.”

A revived No.2 (Leo McKern) is brought before the Prisoner and the Butler (Angelo Muscat).

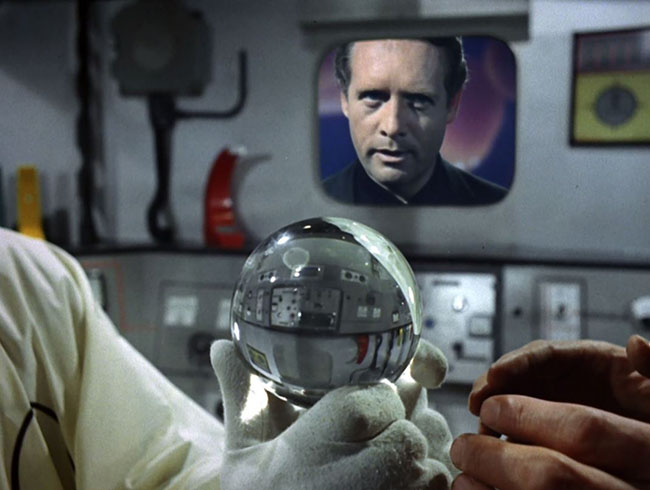

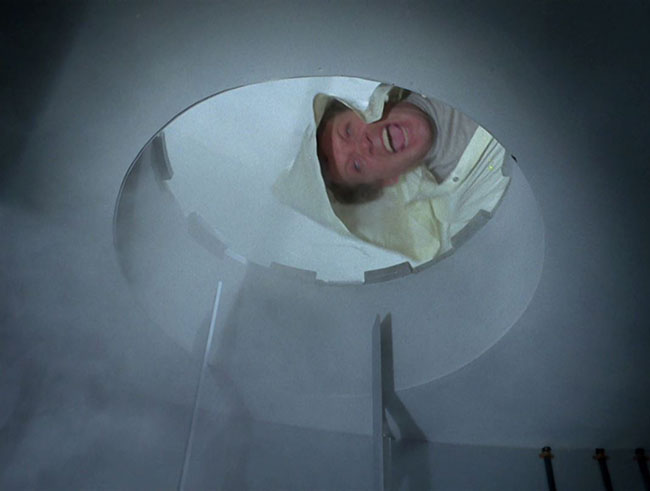

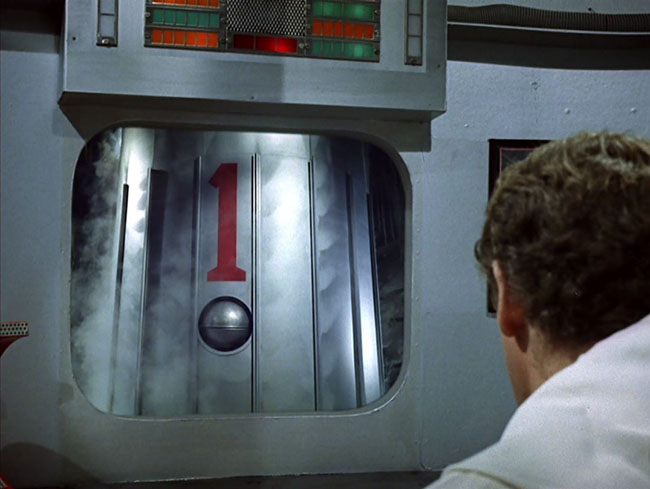

A screen shows a “For Sale” sign being removed from in front of the Prisoner’s residence in London. He is brought forth the key to his home, traveler’s cheques, cash, and a passport, and he’s told that he can either lead the Village or go – wherever he pleases. The President praises him: “He has revolted. Resisted. Fought. Held fast. Maintained. Destroyed resistance. Overcome coercion. The right to be Person, Someone, or Individual is gloriously epitomized in his behavior.” The Prisoner accepts the gifts, not quite decided on whether he should lead or go, and rises to the podium to give a speech. But each time he begins to speak, “I…”, the Assembly parrots back “Aye, aye, aye, aye!” He makes several attempts but cannot be heard over their noise. He ceases, and the President solemnly asks if he wishes to meet No.1. The Prisoner and the Butler descend below the cavern in another lift cylinder, entering a control room with computers. The Butler indicates that he should climb a short spiral stair into a chamber. Inside this room within a room, the Prisoner sees a table of globe maps and a white-robed figure seated before a computer screen showing No.6 declaring that he will not be “pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, briefed, debriefed, or numbered.” The figure slowly turns toward the Prisoner, wearing a mask and holding in his palms a crystal ball. On his robe is the number “1.” On the screen, No.6 repeats “I, I, I, I, I, I…” The Prisoner removes No.1’s mask, revealing a monkey’s mask underneath. He tears this off, and sees his own face under the white hood – a gibbering double, which begins to give chase before disappearing out of a hatch above the control room.

The Prisoner inside Number One’s chamber. Note the familiar phones in the background, including the big red phone.

The Prisoner and the Butler lead a violent revolt against the operators in the Control Room, first with fire extinguishers, and then, as they move into the “Throne Room” occupied by the President and the Assembly, machine guns. “All You Need is Love” is reprised over the carnage. The Prisoner also prepares for launch the rocket which doubled as the “eye” of No.1, and the Village is evacuated before it erupts from underground. The Prisoner, the Butler, No.2, and No.48 escape in the mobile cage, the Butler at the wheel – it is revealed to be a truck as it passes out of a tunnel and onto the open road. After another round of “Dem Bones,” they arrive in London and part ways. No.2 goes to the House of Lords. The Butler enters the Prisoner’s home at 1 Buckingham Place – the door opens and closes behind him automatically, like one of the doors in the Village. The Prisoner boards his Lotus Seven and drives off, recreating the opening credits as he roars down the road. A close-up of his face (as from the credits) is the last we see before the screen goes black.

OBSERVATIONS

It is important to remember that Everyman Films, the production company of Patrick McGoohan credited at the end of every episode, is named after an allegorical play. “Fall Out” is pure allegory with no concessions to realism. The characters are symbols. Alexis Kanner, returning to the show for the third time (after “Living in Harmony” and a cameo in “The Girl Who Was Death“), earns the right to be called not 48 but “Young Man” after the Prisoner bestows the title upon him and No.1 approves (this is more clear in the original script). In the story’s terms he has earned the right to be more than a number, but in fact he has only earned the honor to represent his kind: he is the Young Man, the personification of youths that were part of a social revolution which, by 1968, was quickly becoming commodified by the press and pop culture. Kanner’s character is McGoohan’s own impression of the young hippie, anarchic, dressed in antique clothes, given to “hep” sayings (“Thanks for the trip, Dad!” is his first line). It’s no more authentic than many other portrayals which were cropping up in film and TV, and yet for the purposes of this episode it really doesn’t matter. The Prisoner is now only dealing with absolutes; we are a long way from the nuanced characterizations of, say, “The Chimes of Big Ben.” The President, dressed as and acting like a judge, doesn’t convince as a character that exists beyond the scenes that he occupies. The extras behind him are wearing Greek tragedy/comedy masks, underlining the broad strokes of this play (which is, in fact, both a tragedy and a comedy). Leo McKern’s No.2, one of the rich characters from “Chimes,” is reduced to laughing insanely after “giving a stare” at No.1, but at least he remains the most fascinating No.2 in the series: we learn, for instance, that he appreciated his office but has exhausted his patience, and he rips off his badge to stand beside the Prisoner as another revolutionary in the face of authoritarian control.

Alexis Kern as No.48/”Young Man.”

1968 audiences watching “Fall Out” may have received their first warning when the President starts with, “We crave your indulgence for a short while.” “Once Upon a Time” promised that we would meet No.1, whose presence had been teased since the very first episode, and McGoohan must have been aware that this is all “Fall Out” must accomplish, but that wouldn’t fill up an hour. So he pads things out by giving us theater, a courtroom drama in another dimension. With No.48 going wild singing “Dem Bones” and engaging in a bizarre dialogue with the President – “Give it to me, baby!” the President memorably shouts – I wouldn’t blame viewers who quit then and there. Certainly those loathing McGoohan’s oddball proceedings wouldn’t appreciate the final revelation of No.1, which is allegorical in the extreme. But what a trip, Dad! “Fall Out” is the freakout climax of a one-of-a-kind series, and even if it sets out to frustrate (isn’t that always the goal of The Prisoner: to frustrate audience expectations?), it’s overstuffed with obscure ideas and surreal strokes. It sticks in the memory like gum on your shoe. Consider that the climax features: a massacre set to “All You Need is Love”; Rover shriveling up to the sound of Carmen Miranda singing “I, Yi, Yi, Yi, Yi (I Like You Very Much)”; a meeting between the Prisoner and No.1 that looks like a 70’s prog rock album cover with its masked figure extending a crystal ball by a table set with globes; and a Pythonesque trip to London with McGoohan, McKern, and Muscat. You may not have gotten what you expected or wanted, but you got something.

The Prisoner mannequin.

But most importantly, McGoohan reframes the entire series for the viewer in a hat trick. He forces you to watch it again with the knowledge that No.6 is No.1; he even allows the ending of “Fall Out” to become the opening credits, putting the series in a permanent loop. His most brilliant move is the shot of Muscat entering No.6’s home, with the door opening and closing with the familiar mechanical hum. Everything is the Village. It’s an echo of No.2’s discussion in “Chimes” of the whole world becoming the Village. This drives home McGoohan’s point just as well as, if not better than, the image of No.1 unmasked and raving. We are all prisoners of ourselves. Even when the Prisoner has escaped, he can only loop back to the beginning of another Prisoner episode, the Lotus Seven acting like a malfunctioning time machine that restores him to the same spot as before. Note that the escapees all get a special credit over footage of them going their separate ways – “Alexis Kanner,” “Leo McKern,” “Angelo Muscat” – but McGoohan just gets the credit “Prisoner.” That’s all he is. We never even learn the character’s name, because he will remain a prisoner.

In the Throne Room.

McGoohan admitted in the interview with Warner Troyer that he didn’t know No.6 was No.1 until he sat down to write “Fall Out.” As the deadline loomed, he confessed to ITC’s Lew Grade that he didn’t have an ending. He recalled, “It got very close to the last episode and I hadn’t written it yet. And I had to sit down this terrible day and write the last episode, and I knew it wasn’t going to be something out of James Bond, and in the back of my mind there was some parallel with the character 6 and No. 1 and the rest. And then, I didn’t even know exactly ’til I was about a third through the script, the last script.” When he did arrive at the solution, it refocused the entire series more sharply on a psychological and philosophical level. “This overriding, evil force is at its most powerful within ourselves and we have constantly to fight it, I think, and that is why I made No. 1 an image of No. 6. His other half, his alter ego.” Cleverly, from “Once Upon a Time” and its descent from the Green Dome into the Embryo Room, and then on into this episode and its plunging deeper and deeper from one level to the next, there is a continual excavation of the layers of the Village which parallel the Prisoner penetrating into his own psyche. It is only there, at the very, very bottom, that he can confront No.1. He reacts violently. His revolution is ultimately written with the machine gun fire. He riddles his unconscious with bullet holes to break free, and even this doesn’t liberate him.

The Supervisor (Peter Swanwick), the Butler, and the Prisoner descend.

The reaction from the viewing public was not kind, and McGoohan claimed he had to go into hiding for a few weeks until the furor died down. Perhaps if The Prisoner had been allegorical in each and every episode, the public might have been better prepared. Certainly McGoohan’s scripts, in particular “Free for All,” play on this level; however the series employed a variety of writers, and many of the episodes are quite literal, even if they have touches of the surreal or import science fiction elements. And most people want their entertainment to be literal. It takes a certain sort to appreciate ambiguity, or to acknowledge contradictory concepts which a piece of art might employ: that the Village, for example, can be in Morocco in “Many Happy Returns” and just down the freeway from London in “Fall Out.” But The Prisoner was many things; it contained many genres, many styles; it could be entertainment and it could be Art. “Fall Out” is sometimes awkward, sometimes enervating, often baffling, and prickly and unlovable too. It is not the ending many would like The Prisoner to have. But it is McGoohan’s ending, sometimes wondrous, sometimes obscure, and unapologetic Art.

THE PRESIDENT AND THE ASSEMBLY

This episode introduces us to the elite beneath the Village that surround No.1 without facing him directly. Kenneth Griffith, who had a dual role in “The Girl Who Was Death” as both the mad scientist and No.2, is engaging as the President – officious and dignified until he begins to reveal a bit of Lewis Carroll madness at the edges. His judge’s wig reveals his true role as a judge who can sentence revolutionaries brought before him. The masked Assembly is described in the script as resembling the United Nations. Before each of them is a sign indicating who they represent. These include: Welfare, Pacifists, Anarchists, Identification, Security, Defectors, Education, Therapy, Youngsters, Reactionists, Nationalists, Recreation, Health, Old Folks, Committee, Activists, Board, and Govern. They have a weakness for “Dem Bones.”

The key to the Prisoner’s London home is symbolically offered.

JUKEBOXES

The hallway of jukeboxes is one of the most memorable images in “Fall Out.” We can glimpse albums by Al Jolson, Shirley Bassey, Lesley Gore, Trini Lopez, and two by The Beatles (Something New and The Beatles’ Second Album – curiously, both American albums rather than the U.K. originals). Though “All You Need is Love” plays, the script originally suggested that different songs would compete for attention: “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Little Boxes,” “Toot-Toot-Tootsie Goodbye,” “Hello Dolly,” “Yellow Submarine,” and “All You Need is Love.” (“Or whatever,” the script says.)

PORTMEIRION

For the first time in the series, the shooting location is revealed in the credits – and prominently, too: right before the title “Fall Out” appears. A special thank you is given to Sir Clough Williams-Ellis and his Hotel Portmeirion.

6 OF 1…

It’s curious that McGoohan didn’t know that No.6 was No.1 until he wrote “Fall Out,” given that one could read clues into many of the episodes. Most tellingly, No.6’s residence has the address of “1” right there on its door, a fact which is highlighted again at the end of this episode. In the standard opening credits exchange between No.2 and No.6, 6 asks, “Who is Number One?” and No.2 replies “You are Number Six.” Add a comma and the response becomes an answer rather than a deflection. McGoohan stated that when his staff read the script, a few of them said they’d figured it all out long ago.

Number One.

REVOLUTION 1

“But when you talk about destruction

Don’t you know that you can count me out (in).”

-The Beatles, “Revolution 1”

The surprising inclusion of “All You Need is Love” – all the more surprising given how rarely Beatles music is licensed for film, let alone TV – perfectly tethers the show to the pop culture moment of 1967-68 and ideas percolating up from the counterculture. (McGoohan would have disapproved, but honestly, was there a better TV show for those experimenting with drugs?) The song debuted on Sunday, June 25, 1967, as Britain’s contribution to the worldwide live event Our World, which was, to quote the BBC press release, “linking five continents and bringing man face to face with mankind, in places as far apart as Canberra and Cape Kennedy, Moscow and Montreal, Samarkand and Söderfors, Takamatsu and Tunis.” The Beatles performed the song live on the broadcast to a pre-recorded rhythm track. It was issued as a single (b/w “Baby, You’re a Rich Man”) on July 7 and reached the top of the charts quickly in the U.K. and the U.S. McGoohan gives added (if almost subliminal) prominence to the Beatles by displaying two of their Capitol Records albums in the jukeboxes that the Prisoner walks past.

The song is used twice in the episode. When it first appears, it is triumphant: the Prisoner is on the cusp of finally achieving his goals and being free. But after the trial of “revolt” and the confrontation between the Prisoner and his dark inner self, he turns to violence, doing something John Drake wouldn’t and picking up a gun – as he did in “Living in Harmony,” an episode I described as a moral failure on his part. While he mows down his enemies, “All You Need is Love” plays a second time, ironically, but also to suggest that sometimes revolution might require brute force (when all else fails). He even launches the No.1 rocket, which implies the destruction of the Village. But this doesn’t work either – he is as much a prisoner at the end of the episode as he is at the beginning of the series, though one could superficially accept the events as they’re presented and believe he has finally escaped.

The Prisoner prepares to launch the rocket, with Number 1’s electronic eye.

In May 1968, a few months after “Fall Out” shocked and outraged British viewers, the Beatles began work on John Lennon’s new song “Revolution,” its lyrics shaped like a dialogue with a young revolutionary (perhaps Young Man himself) and expressing Lennon’s complex feelings on the topic. Lennon’s music would become increasingly political as he moved into the arena of solo artist, with “Give Peace a Chance” becoming an anthem for the young people around him who wanted to change the world for the better. “Revolution” was directly inspired by 1968 anti-war protests and the violent responses from police. Ultimately three different versions would be recorded. The single (a double-A sided single with Paul McCartney’s “Hey Jude”) was a blistering rock song. But the two versions on their 1968 “White Album” (The Beatles) were radically different. “Revolution 9,” birthed from outtakes from a particularly wild take and inspired by Yoko Ono’s art gallery happenings, was an avant-garde sound collage which attempted to capture the sometimes terrifying sounds of a revolution.

There was also “Revolution 1,” so named because it was the song’s first incarnation and the one which Lennon preferred, a slower, doo-wop take. In this early version, he hadn’t yet decided whether “destruction” was necessary in a revolution, and instead of saying “you can count me out,” as he did in the single version, he gave a more ambivalent response: “You can count me out…in.” McGoohan seems to take a similar stance in “Fall Out.” “All You Need is Love,” but sometimes sticking flowers in the nozzles of guns, Young Man, will not do the trick.

THE VILLAGE

“Fall Out” recasts the Village as a metaphysical place, located inside the Prisoner’s mind. At least, this is one possible interpretation. One can revisit the series with this knowledge and certain episodes (“Free for All,” “Dance of the Dead“) make more sense than others. But the overall theme that the Prisoner’s cage is of his own making is, to my mind, a satisfying resolution.

The Butler retires to the Prisoner’s home.

RANKING THE EPISODES

See my notes in “The Girl Who Was Death” (under “Sequence”) as to my Prisoner episode sequencing, including an overview of the logic I applied and the narrative this sequence tells.

Here is a completely subjective ranking of the Prisoner episodes. “Fall Out” is the most difficult to rate since it really stands on its own, but I’m making an attempt nonetheless. My enthusiasm only dwindles with the last couple of episodes on the list (and the lowest is the only one that I could do without); please don’t think that just because something is in the middle or lower half of this list means that I find it mediocre.

1. Once Upon a Time

2. Free for All

3. The Chimes of Big Ben

4. The Schizoid Man

5. Arrival

6. A. B. and C.

7. Living in Harmony

8. Hammer Into Anvil

9. Fall Out

10. Many Happy Returns

11. Dance of the Dead

12. Checkmate

13. The General

14. A Change of Mind

15. The Girl Who Was Death

16. It’s Your Funeral

17. Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling

BEYOND THE PRISONER

The Prisoner found an immediate life outside its TV run in a short series of tie-in novels: Thomas M. Disch’s The Prisoner, Hank Stine’s A Day in the Life (look: another Beatles reference!), and David McDaniel’s Who is Number Two? Other Prisoner books have been written by Roger Langley (Think Tank, Charmed Life, When in Rome) and – more recently – Jonathan Blum and Rupert Booth (The Prisoner’s Dilemma) and Andrew Cartmel (Miss Freedom). There has been a great deal of fan fiction, including my own 1995 novella Soliloquy which was published by the American fan club Once Upon a Time. DC Comics acquired the Prisoner license in 1988 and created a miniseries sequel to “Fall Out” called Shattered Visage, written by Dean Motter and Mark Askwith and illustrated by Motter. This follows a young woman who is washed ashore in the Village, now abandoned, and encounters No.2 – actually an aged No.6. It’s well done, a somber epilogue to the series that perhaps works best in graphic novel form.

Patrick McGoohan wrote a script for a feature film sequel to The Prisoner, but it was never produced. Film remakes were threatened over the years, but nothing surfaced until the 2009 miniseries written by Bill Gallagher and starring Jim Caviezel as No.6 and Ian McKellen as No.2. I haven’t watched it since it aired, but it left a sour taste. The positives: the desert setting for the Village was a smart substitute for Portmeirion, emphasizing both the Prisoner’s isolation and the surreal nature of the story. McKellen is an excellent choice for No.2, and Rover was well realized (I think – it’s been a while). The negative: the decision to make the series one serialized story with subplots and character conflicts that depart from the core theme of the show, and a disappointing resolution in the final episode. Take my criticisms with a grain of salt, though, because it’s been eight years since I’ve watched it. Caviezel would go on to the much more successful Person of Interest, which picks up on some of the themes of The Prisoner.

The most successful post-Prisoner adaptation I’ve encountered is the audio drama by Big Finish Productions. Written and directed by Nicholas Briggs and featuring Mark Elstob as No.6, this series strikes the perfect balance between homage and reinvention. The original stories (sprinkled in with remakes) could easily be slipped into the original series, and Briggs – unlike many of the writers to attempt The Prisoner over the years – really “gets it.” A second volume of episodes is due out around August of this year.

CONCLUSION

That wraps up Midnight Only’s coverage of The Prisoner, aging quite well 50 years on. Be seeing you.

QUOTES

The Prisoner: Don’t knock yourself out.