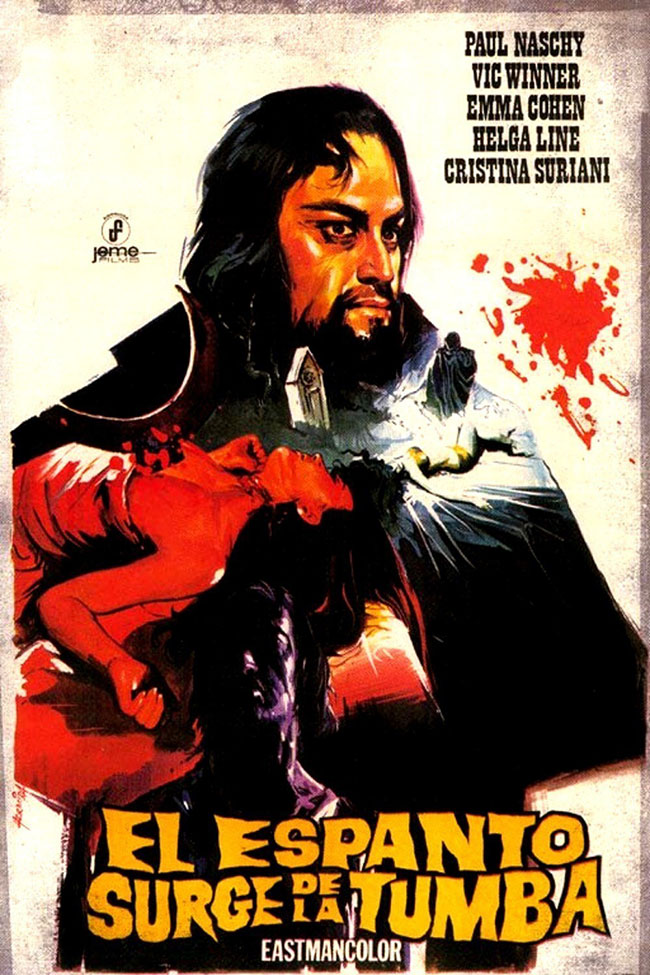

Scream Factory’s new 5-disc, 5-film set The Paul Naschy Collection seeks to bring wider exposure to Spain’s horror auteur, writer/director/star Paul Naschy. Scream has modeled this set after their three indispensable volumes of Vincent Price films, which I hope means this will be just a first installment. Of course Naschy has been well known to Eurocult fans for a long while. His most prominent recurring role was the Lon Chaney Jr.-styled werewolf Waldemar Daninsky in films such as La Marca del Hombre Lobo (1968, released in the States with the unlikely title Frankenstein’s Bloody Terror) and La Noche de Walpurgis (aka Werewolf Shadow or The Werewolf vs. the Vampire Woman, 1971). But Naschy also strongly identified with the demonic undead warlock Alaric de Marnac, who appears in the first film on Scream Factory’s collection, Horror Rises from the Tomb (El Espanto Surge de la Tumba, 1972). De Marnac is the Headless Horseman, Dracula, and Bela Lugosi’s zombie overlord from White Zombie all rolled into one. And that’s what I like about Naschy’s approach to horror: he doesn’t discriminate; all horror tropes are fair game. Horror Rises from the Tomb, directed by Carlos Aured (Curse of the Devil), begins like Black Sunday (1960) before unexpectedly turning into Night of the Living Dead (1968) for a short while, then embraces vampire iconography with equal parts Lugosi, Christopher Lee, and Jean Rollin. Gratuitous gore and nudity are abundant, and the pace never slows. If you like 70’s exploitation films at all, it’s hard to not enjoy the madness that Naschy is up to.

A séance summons the disembodied visage of Alaric de Marnac (Paul Naschy).

In an evocatively shot prologue set in 15th century France, Alaric de Marnac (Naschy) and Mabille de Lancré (Helga Liné, Nightmare Castle) are escorted through a misty valley to their execution for the crime of practicing witchcraft. De Marnac is ordered to have his head removed and buried separately from his body. In the present day, his descendant Hugo de Marnac (Naschy again) attends a séance with his friends, including Maurice (Victor Alcázar) – whose lineage also dates back to the days of Alaric de Marnac – and Elvira (Emma Cohen, Cut-Throats Nine). The séance summons the spirit of de Marnac – or his head, at any rate – who gives the exact location where his head has been buried by speaking through the medium’s lips (an effect both eerie and silly). This prompts a journey to an ancient estate to verify the spirit’s claims – actually Naschy’s own family home, which provided the suitably Gothic shooting location for many of his films. Along the way they encounter highwaymen who are immediately dispatched by the bloodthirsty, lynch-happy locals, the first of many bizarre scenarios which unfold throughout the film. The estate’s caretaker wields a sickle and is intent on resurrecting de Marnac (a set-up similar to the one in Dracula: Prince of Darkness), so good thing Hugo and Maurice just arrived to dig up the warlock’s severed head. Maurice, who has been secretly, obsessively painting images of the decapitated de Marnac under the ghost’s malevolent influence, is psychically given the precise GPS coordinates to dig up the desired head, which is perfectly intact. The caretaker – after using his sickle to kill off a teenage girl to whom we’ve just been introduced – steals the head and takes it to a hidden shrine. Maurice now falls completely under the thrall of de Marnac and assists in his resurrection, as well as that of de Marnac’s lover Mabille de Lancré. The two raise zombies and begin to prey on the locals by sneaking into their bedchambers Dracula-style, seducing and killing them. They also sleep in matching coffins.

A Rollin-esque epilogue with Emma Cohen as Elvira.

I’ll be honest, I couldn’t keep track of all the characters introduced, disrobed, and slaughtered. Apart from Naschy’s multiple roles and the Barbara Steele-like performance by Liné, the biggest impression is left by beautiful Emma Cohen as Elvira, whose role gets larger as the story deliriously progresses. Surprisingly, it is she, not Naschy’s Hugo, who thwarts the evil plot using a talisman medallion and a silver needle. In a final image straight out of Rollin’s oeuvre, she stands on a shore in the pre-dawn hours while snow (or ash?) falls around her and drops the medallion in the water. (It is typical of the film’s dubbing that the splash has a few seconds’ delay.) There are other stylish touches throughout the film: Hugo fighting off zombies with his swinging torch, lighting them on fire as they come close; de Marnac’s defeat, as blood suddenly appears at the seam in his neck – his sorcery is undone, and his body is splitting in two again. But the film’s greatest value is its fever dream approach to narrative, taking us from one familiar image to another like a tour of the last few decades of horror film, nothing quite sticking but everything punched up to maximum effect. Although Scream Factory was not permitted access to the original elements for the Naschy films in this collection, Horror Rises from the Tomb looks fantastic, and among the extras are “alternate clothed sequences” from the more chaste print which could safely screen in Spain. The other films in The Paul Naschy Collection are Vengeance of the Zombies (1972), Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll (1973), Night of the Werewolf (1980), and Human Beasts (1980).