Escape from New York (1981) is squeezed tightly into the middle of John Carpenter’s career hot streak, when he was releasing at least one film a year. Halloween (1978) was a runaway horror smash, but Escape from New York was the sleeper action movie that kicked him into the Hollywood big leagues for a strong run through the rest of the 80’s. (Strong, at least, creatively – it’s easy to forget that The Thing and Big Trouble in Little China disappointed at the box office, and that his top-grossing film of that decade was actually Starman, a movie that’s now neglected among Carpenter fans.) As Snake Plissken, Kurt Russell, who had come up in Disney movies and TV guest spots, completed an astonishing career reinvention that began with Carpenter’s Elvis (1979) and the hilarious R-rated Robert Zemeckis comedy Used Cars (1980). He was now a take-no-shit action hero, and no one would doubt him. Carpenter’s choice to build up the audience’s awe of Russell is to have everyone in the film talk about him: he’s incarcerated for robbing the Federal Reserve depository; before that, he pulled off some kind of dangerous covert mission; and everyone in the cast knows who he is (and, in the film’s best running joke, thought he was dead). The decision to not give Snake Plissken a conventional introduction was one made in the editing room. Carpenter had shot the bank robbery in a seven-and-a-half minute sequence where Plissken, carrying a billion dollars in stolen money, attempts an escape to San Francisco with his partner, who’s shot dead by police before Plissken is captured. It’s easy to see why it was cut: the film takes its time getting going, and this would prolong Snake’s infiltration of Manhattan Island even more. But it’s worth noting a few things: this is not a James Bond-style pre-credits scene; the intention is not to provide action spectacle or to show off Plissken’s skills, which is what other directors might have done to sell the new Kurt Russell. The somber lighting and feeling of impending doom in this deleted scene match the tone of the rest of the film, and it’s not Plissken’s combat ability that’s established, but his character. The fact that he gives himself up in the act of trying to save his partner would have deepened the impact of the film’s final scenes, especially his last exchange with the President (Donald Pleasence). Yet by removing any kind of introduction, we are left to Plissken’s legend and the rumors others tell about him. The deleted scene shows that he’s human. In the final cut of the film, it’s quite a while before we catch glimpses of his capacity for empathy. We only know the Snake that others have described while he stalks (and eventually limps) his way through a fallen Manhattan. Thus Carpenter wills Russell into becoming the new Clint Eastwood.

Police Commissioner Hauk (Lee Van Cleef), monitoring Snake’s progress from the outside.

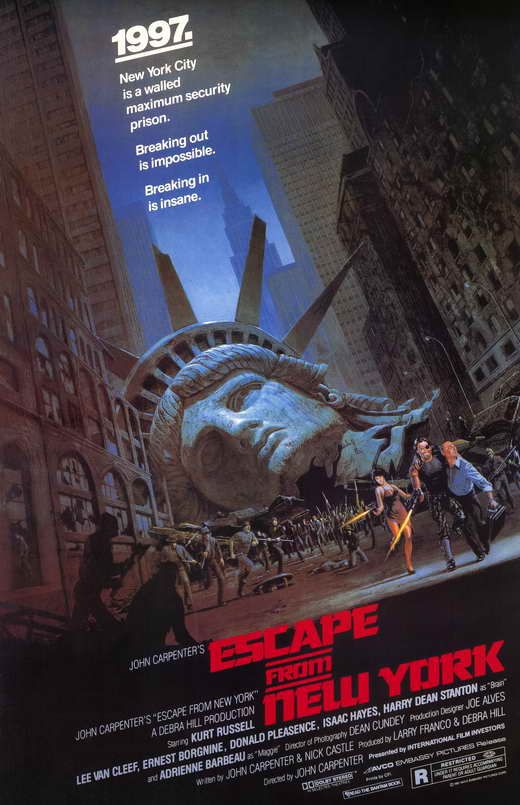

Carpenter fans know that the director loves Westerns. The Western is often about the build-up – meeting colorful characters in an isolated town, an agonizing moral decision, the escalating tension before a quick and violent climax. We believe what everyone says about Plissken as soon as the eyepatch-wearing Russell sneers at a genuine Western badass, Sergio Leone veteran Lee Van Cleef. Despite its high concept in the near-future of 1997, Escape from New York is a Leone Western at heart, the audience placing its trust in an antihero, a futuristic Man with No Name, because the world he navigates is populated by the corrupt, the murderous, and the depraved. As with most Westerns, the action is actually pretty sparse, Carpenter favoring scene-setting and the suspense of a ticking clock, his plot given a High Noon-style deadline when our hero may die. The premise is irresistible: as the opening titles tell us, in 1988 the crime rate rose 400%, and in a desperate move, the entire island of Manhattan was transformed into a maximum security prison, surrounded by mined bridges, mined waterways, and towering walls. Within, the criminals may do as they please among the dilapidated skyscrapers and trash-strewn streets. Nine years later, Air Force One is hijacked by a militant group and crashes inside Manhattan Island. The President, whose heart rate is monitored through a watch, is believed to have survived in an escape pod, but when Van Cleef’s Commissioner Hauk and his heavily armored police officers helicopter inside the prison, a creepy punk (jokingly named Romero, and played by Frank Doubleday) claims that the “Duke” has the President and will kill him if they don’t leave immediately. Hauk sends for Plissken and offers him a deal: he’ll be pardoned and released if he can retrieve the President within 24 hours. He must also bring back a cassette the President is carrying, which contains a message key to the success of nuclear talks in a summit with China and the Soviet Union. The catch: if Plissken doesn’t return with the President and the cassette by the deadline, capsules injected into his arteries will completely dissolve, triggering a miniature explosion that will kill him instantly. Only Hauk, who will be waiting outside the prison walls, can neutralize the capsules. Plissken sets off in a glider in the middle of the night, landing on one of the towers of the World Trade Center and tracking the President’s pulse-monitoring watch.

The Duke (Isaac Hayes) uses the President for target practice.

Despite its reputation as an action film, there aren’t a lot of action scenes here, with the first major one – a fight between Plissken and a towering opponent in a gladiator arena in Grand Central Station – coming just before the film’s third act and well over an hour in. Most Westerns don’t have a lot of action, either, but the constant threat of violence is important. Carpenter even dips into the horror genre that made his name: the mean streets of early-80’s New York City are satirically heightened for 1997, Times Square disrepute transformed into Dawn of the Dead danger, Romero-punk and all. We learn there are various gangs (the Skulls, the Turks) that have claimed ownership of various streets and boroughs, but none more frightening than the Crazies, who live in the sewers and come up at night for food, pouring out of manhole covers, killing Plissken’s first contact (who’s just been introduced!) and chasing him through a derelict building. And whatever you do, don’t drive down Broadway. One of our guides through this nighttime world is Cabbie, played by Ernest Borgnine (another veteran of a classic antihero Western, Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch). Cabbie knows everyone, and is smart enough to know where to go and where not to go: in one funny scene he peels off in his cab while Plissken and his companions are still pondering their next move. Carpenter keeps us unsettled with one of his trademark scores, a pulsing synth that beats behind every scene like the two tracked heartbeats we trace throughout the film, the President’s and Plissken’s. (The memorable main theme will be featured on the upcoming John Carpenter album Anthology: Movie Themes 1974-1998, which he’s touring to support. Here’s his promo video for Escape from New York.)

Adrienne Barbeau as Maggie.

Has there ever been a more perfectly cast genre film? Soul singer and Shaft composer Isaac Hayes plays the Duke as a kingpin confidently ruling the new Manhattan, the hood of his Cadillac decorated with chandeliers. He prizes the President as a negotiating tool, but isn’t above using him for target practice. Harry Dean Stanton (Alien) is The Brain, who has turned his lair into an oil refinery, providing gas for the Duke; Snake knows him from a former life as Harold Hellman. (“Don’t call me Harold,” Stanton mutters.) Carpenter’s then-wife Adrienne Barbeau (Swamp Thing) plays the Brain’s partner Maggie, perhaps the film’s most sympathetic character despite her moral ambivalence. Van Cleef’s advisor Rehme is played by Tom Atkins, who would graduate to a lead role in the Carpenter-produced Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982). And, of course, there is Dr. Loomis himself, Donald Pleasence, as the President (“President of what?” Snake asks). The film’s treatment of this character is interesting. We feel for Pleasence when he’s first discovered, still shaking in fear from the treatment by his captors, just as we sympathize when he’s being shot at and humiliated. We understand that he’s a fish out of water, a stuffy authority figure. But it’s when he seems completely unaffected by the sacrifice of those who died saving him that Plissken turns against him in the film’s final scene. The President fails Plissken’s test; on this level, he doesn’t meet the moral standard set by our antihero. In its belated sequel, Escape from L.A. (1996), Carpenter makes the implications of this choice even more explicit, as Plissken ultimately sends the world back to the Dark Ages. It’s the ultimate middle finger: maybe the world does deserve to burn, if we can burn the corruption away. (I have to note that on this viewing the message didn’t resonate with me at all. I’d probably vote for Pleasence’s character, depending on who else was on the ballot. So he’s a tool? So what? There are worse things, and these days I’d like to vote for the man who’s trying to avert nuclear war, as cool as I find the guy in the eye patch.) Still, in the context of the film, the 69th Street Bridge climax and the “Bandstand Boogie” denouement are crackerjack. Carpenter prefers abrupt endings, and sometimes they don’t work, but the model is Escape from New York, which ties up all its loose ends in a neat and clever fashion. By doing so, he crafted another perfect low-budget thriller. As with Halloween, imitations followed, like Enzo Castellari’s 1990: The Bronx Warriors (1982) and Escape from the Bronx (1983). But Carpenter would use this film’s success as a springboard for a major opportunity at Universal, and it would produce what might be his best film: The Thing.