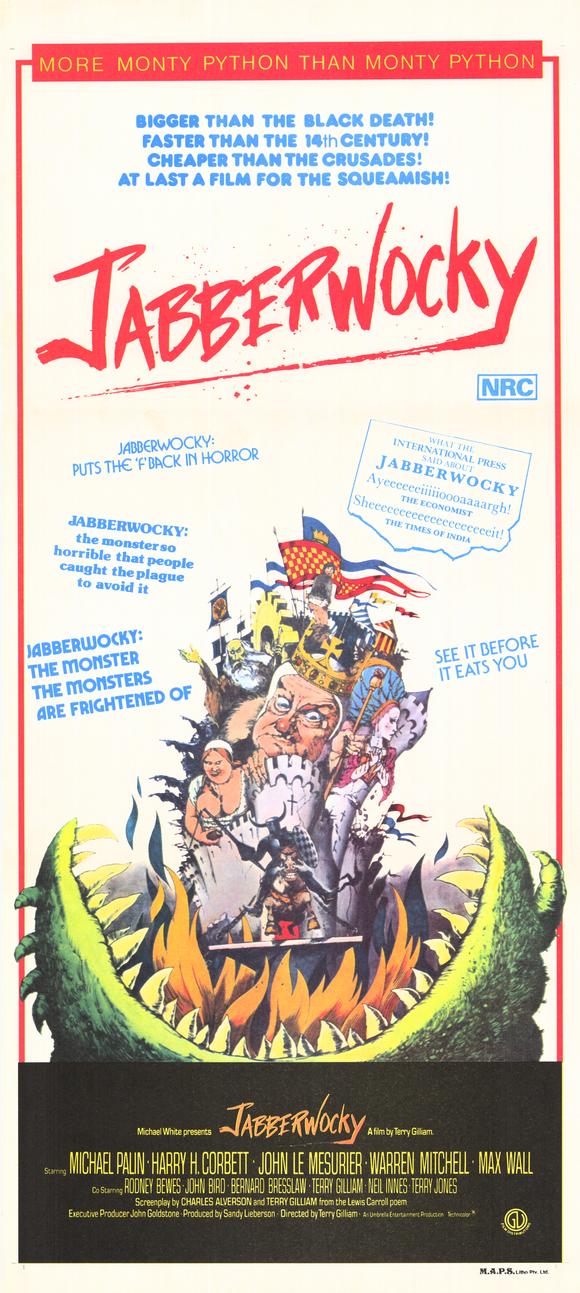

The nonsense title of Jabberwocky (1977), taken from a Lewis Carroll poem written in nonsense words (in Through the Looking Glass), could not be more appropriate, because it is a proudly nonsense film. It also defies categorization, or even easy comprehension. It’s a prickly and at times cumbersome and lumbering beast. Terry Gilliam’s first directing effort outside of Monty Python and his first solo directorial credit, it is a strange medieval satire, so committed to its grubby authenticity and labyrinthine world that at times it’s hard to see the sky, metaphorically speaking: there’s just so much filth and chaos and conflicting tones of poetry and vulgarity and sprawling, untidy ideas. You are in Gilliam’s garage, rummaging through boxes and boxes of his surreal sketches. As such, it’s often been dismissed and neglected, especially since his work feels considerably more polished beginning with his next, Time Bandits (1981); Jabberwocky is like a trial run. But it also feels like a purging of drawerfuls of ideas that had been backlogging in his mind while laboring on Python cartoons through long nights, and so what you get is dazzling in its imagination and gleeful in its indulgence. Most of all, it’s overwhelming – and long, at almost two hours (it feels longer). I’ve never preferred the use of the adjective “uneven” in writing about films, but if ever there was a picture that deserved it…no, let’s try another approach. This is not so much a movie as a Cabinet of Gilliam Curiosities. It is not something to evaluate as a whole, but to explore, and to discover something new on each excursion.

Max Wall as King Bruno the Questionable (with Neil Innes in a cameo as a herald).

Gilliam and Terry Jones had shared the director’s chair for Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1974) and, famously, did not see eye to eye, each taking steps to undo the other’s work during production. Gilliam’s frustration at Jones’s unwillingness to shoot scenes the way he had envisioned them was one thing. But he was also exasperated with the Pythons as actors (Cleese giving the most resistance to standing around in the mud and rain waiting for Gilliam to stage the best possible shot). Jones had a much better rapport with the Pythons, and so Gilliam was happy to cede the chair to him for subsequent Python films; it should also be noted, in Jones’s defense, that he was skilled at shooting a scene for maximum comic impact, as Life of Brian (1979) attests. Having this popular Python lore in mind is helpful in understanding the origins of Jabberwocky. It’s Gilliam’s statement of This is the movie I’d have made. In many ways it’s the experimental B-side to Holy Grail‘s pop single, taking that film’s commitment to medieval grubbiness and adding buckets more of piss, shit, gruel, and blood. But he gets to stick the camera where he wants to, and despite the bodily fluids, this film is gorgeous to behold; since I have never seen this film projected theatrically, it’s a factor that I hadn’t appreciated until recently viewing Criterion’s Blu-Ray, released last November from a 4K restoration. While the story stumbles clumsily along, you can appreciate the individual setpieces for how strikingly composed they are. I actually gasped at the beauty of a shot from what I used to consider the most disgusting part of the movie, as our naïve protagonist rows his boat over to the Fishfinger place to court the indifferent peasant girl Griselda (Annette Badland). He gets pissed on by the young son, and Mr. Fishfinger (Warren Mitchell) talks to him while shitting out the window. Yet on this Blu-ray, the sun-dappled waters are bathed in a low mist, the surrounding greenery is rich with atmosphere – you can feel the romance of our misguided hero, oblivious to the grotesqueries he’s trying to charm. Gilliam has often citied Bruegel and Bosch as the inspirations for Jabberwocky, and this is the first time the film has really captivated me on the visual level.

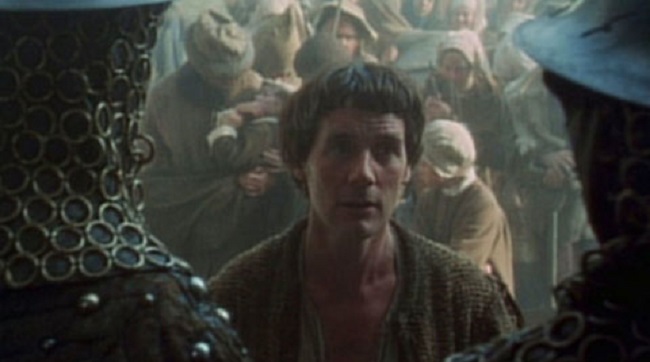

Michael Palin as Dennis Cooper.

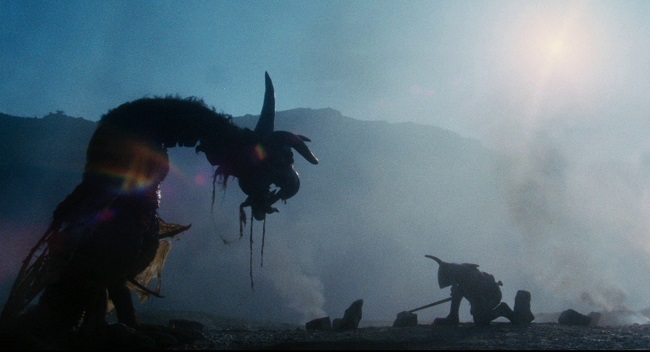

It wasn’t a clean break from Python. Gilliam does bring along Michael Palin as lead (the “Nice Python”), and provides cameos to Jones and friend-of-the-Pythons Neil Innes – even if he gives Jones a rather brutal death by Jabberwock before the opening credits. As a result, the film was issued in some places with a poster calling it Monty Python’s Jabberwocky, which could only make a problematic film look more problematic. (Amazingly, this incorrect title also made it onto one of the VHS releases.) Gilliam’s co-writer, however, was Charles Alverson, an American satirist and novelist whom Gilliam had worked with during his years at Harvey Kurtzman’s magazine Help! Apart from Palin, the cast is filled out with new collaborators, actors who are only too eager to subject themselves to the director’s scatological, absurdist, farcically cruel world. Coming off best here are the royals, sequestered from the world in their crumbling castle: legendary British comedian Max Wall as the gentle and oblivious King Bruno the Questionable; Deborah Fallender as a delusional, tower-bound princess who just needs a prince, any prince; and John Le Mesurier as King Bruno’s eternally patient, even loving Chamberlain. Gilliam effectively sets up the stratification of this little kingdom, with the privileged sealed off from the world in the shadows and decay of their castle keep, occasionally venturing out for the good old-fashioned bloodbath of a tournament; the villagers struggling to make a living within the castle walls and in its crowded, bustling streets; and those too poor to gain passage through the gate, living in a shantytown outside the wall and easy pickings for the roaming, bloodthirsty Jabberwocky (which gets a late but spectacular reveal). Palin’s Dennis Cooper takes a picaresque journey through all these worlds, but all he really wants is the hand of Griselda Fishfinger, and carries not a lock of her hair but a discarded potato out of which she’s taken a bite.

The Princess (Deborah Fallender), the King, and the Chamberlain (John Le Mesurier) enjoy some jousting.

Jabberwocky has almost nothing to do with the Lewis Carroll poem – we hear it recited throughout the film, but we are definitely not in Wonderland. Yet it’s flush with great ideas, many of which are individual details such as that potato, which starts to sprout over the course of the film but only becomes more precious to Dennis. Individual scenes work very well, notably a ridiculously overmanned blacksmith assembly line that explodes into chaos and destruction when Dennis tries to make a minor efficiency improvement, or the King gifting a tower to his daughter, which we see immediately collapse as soon as he’s finished his sentence. The tournament is the most Pythonesque scene in the movie, an escalation of the bloody Black Knight duel in Holy Grail, though cleverly we never see any maiming, just the blood; this somehow ends with the knights playing a child’s game of hide and seek. But one can’t help but think that the story is marking time before the final act, a very solid stretch of action, imagination, and parody in which Dennis becomes squire to a knight on a quest for the Jabberwocky and ultimately becomes the fairy tale hero, through no intentional act of his own (and not an ounce of character growth). This clever subversion of myth is the main card that Gilliam has to play, and he sells it when the time comes, with a hilarious ending in which everything goes according to script but the hero, our unambitious Dennis, is horrified – winning half the kingdom and being wed to the princess rather than Griselda. You might also note that the rapid pacing of this final twist is unlike anything else in the film – it has a sprightly comic rhythm which Jabberwocky could use heaping portions of. Well, Gilliam would learn; he’d made his point, and better (and more entertaining) films were ahead.