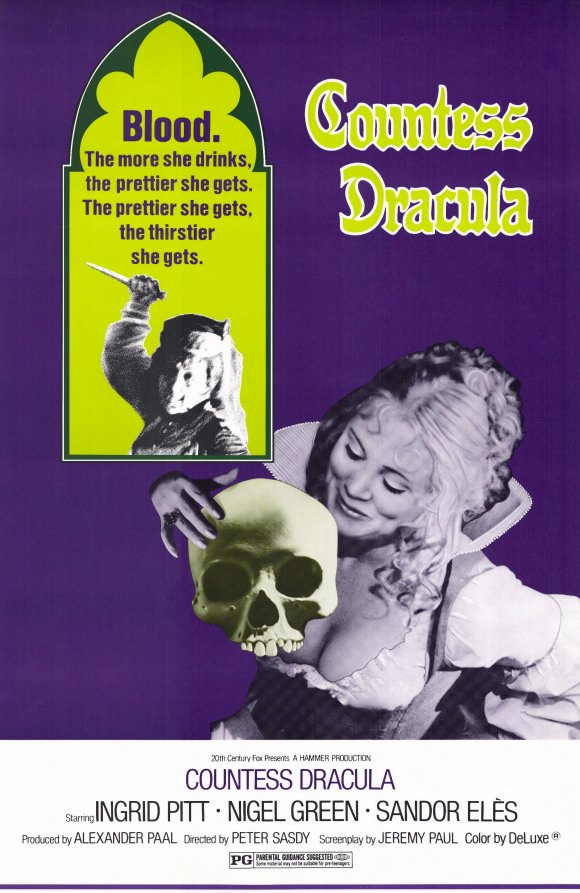

As Hammer moved into the 70’s, the loosening of censorship and the desperation to stay relevant amidst the increasingly edgy horror market led to more overtly exploitative fare, with rampant sex and nudity. The best known extension of this formula was the informally linked “Karnstein Trilogy,” three vampire films which included the Carmilla adaptation The Vampire Lovers (1970), Lust for a Vampire (1971), and Twins of Evil (1971). All three were rich with breast-exposing and breast-biting, though two of them (excluding Lust) managed to do so with a compelling story and strong acting, elevating the films in their particular subgenre. A first cousin of the trilogy is Hammer’s Countess Dracula (1971), with Vampire Lovers star Ingrid Pitt playing not a female Dracula but a fictionalized version of the notorious 16th-17th century murderess, the Countess Elizabeth Báthory, who was rumored to bathe in the blood of virgins to preserve her youth. (This colorful detail remains in dispute, though there is no doubt that she committed numerous atrocities against the young peasant women brought to her castle, including torture, murder, and possibly cannibalism.) Given the fact that the Countess’ holdings included land in Transylvania, and that the title uses her latter-day nickname “Countess Dracula,” it could even be argued that this film should be slotted into Christopher Lee’s Dracula series as a more organic alternative installment than The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974), which featured a non-Lee Dracula and…kung fu (I’d also argue that Countess Dracula is much better than 1970’s official entry in the series, Scars of Dracula). Whatever the context, this film is often unfairly overlooked. It’s a flawed but deliciously cruel fairy tale about vanity.

Countess Elisabeth (Ingrid Pitt) uses the blood of virgins to become young again; she impersonates her own daughter to catch the attention of the handsome Imre Toth (Sandor Elès).

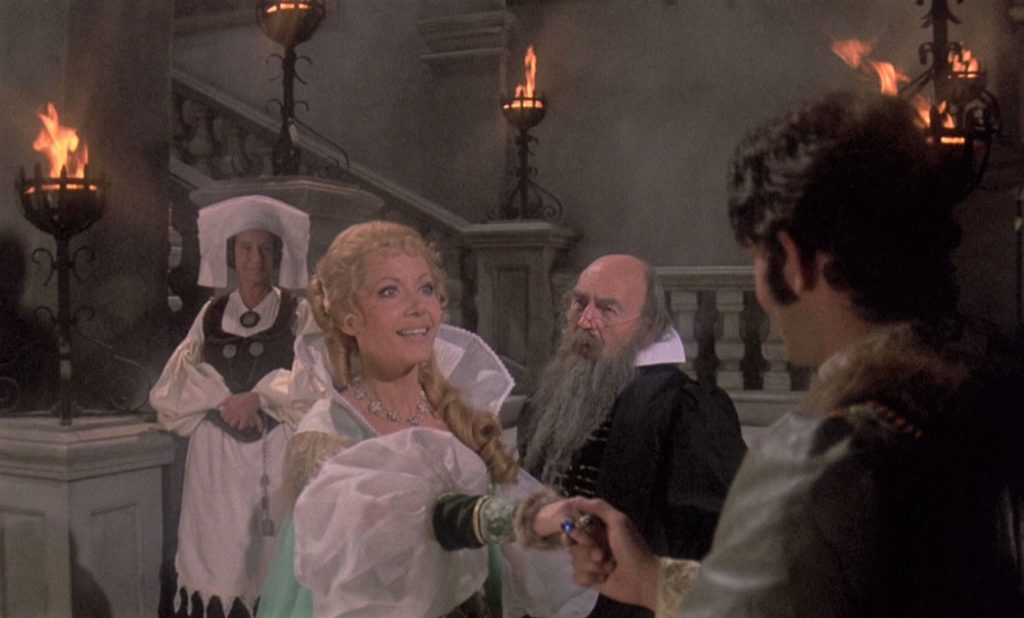

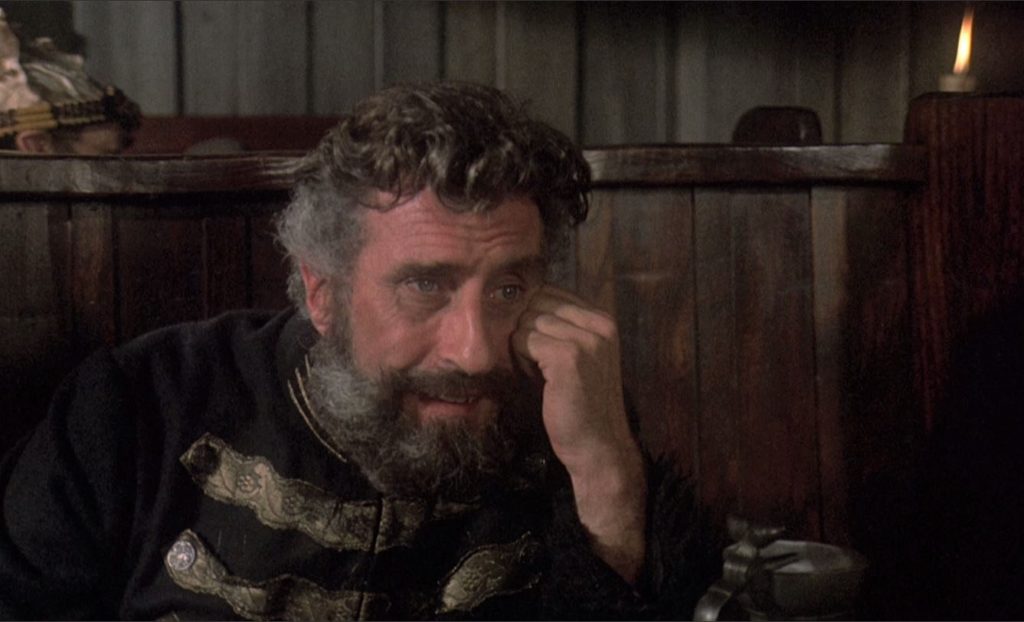

Pitt’s Countess Elisabeth is an old crone whose husband has recently died. She’s disappointed to learn that his will dictates that she split the estate with her daughter Ilona (Lesley-Anne Down, The Great Train Robbery), who has been away for many years and will soon be arriving by coach. After a fight with a servant girl that ends with a slash and a spurt of blood, Elisabeth is astonished to discover that the red spatters on her cheek have erased her wrinkles. Her maid Julie (Patience Collier, Fiddler on the Roof) is asked to bring her young girls so that she can use their blood to rejuvenate her flesh, a plot quickly discovered by Captain Dobi (Nigel Green, Jason and the Argonauts), the man who had been hoping to marry the newly-widowed countess. Dobi barely bats an eye at the transformation: “And what will your daughter say when she arrives tomorrow and finds you as young as she is?” Well, the answer is kidnapping young Ilona so she doesn’t arrive at all – she’s kept hostage in a hut by an idiot hermit – leaving Elisabeth the opportunity to impersonate her daughter and romance her father’s war buddy, Imre Toth (Sandor Elès, Love and Death). Dobi, who would have been satisfied with the older Elisabeth, can’t help but be jealous of the younger Imre, who gets engaged to the Countess. Dobi even tries to sideline the man with a tavern wench so that the captain can enjoy an evening in bed with the younger Elisabeth (and perhaps get Imre caught cheating). But when he learns that Elisabeth’s beauty has a Cinderella-like expiration period, he becomes repulsed by her. He shatters Imre’s illusions eagerly, allowing the young soldier to walk in on his fiancée while she’s taking a bath – in the blood of a virgin.

Elisabeth is exposed.

Though Countess Dracula is slow-moving at times, and lacks some of the entertaining excesses of other Hammer films of the period, I find it a strangely powerful film as it moves into its final act, a wedding scene in which Elisabeth is the only one present who is happy to be there. Her fiancé has become a hunched-over, quiet, and distinctly shattered man, fully aware that he is marrying a murderess and an impostor but compelled to her wishes (“I have witnessed so much blood my very being reeks of it,” he says). Captain Dobi has given himself over to cynicism completely; he has murdered Master Fabio (Maurice Denham, Night of the Demon) to keep Elisabeth’s secret, and attends the wedding of the damned without protest. The only spark of hope is the belated arrival of the real Ilona, which awakens enough of the spirit of Imre and the maid Julie to help her escape the castle. Meanwhile, Pitt owns the film with a pseudo-dual performance that begs the question of why she wasn’t a bigger horror star. As the older Elisabeth, she’s bitter, haggard, and desperate, ranting and sobbing; as the younger version of herself, she’s the life of the party, charming and sensual – it’s easy to see why Imre falls for her and why Dobi begins to desire her in a way that he hadn’t before. (It seems his love is erased by a more surface-level lust.) The Polish-born Pitt, who had a breakthrough in Where Eagles Dare (1968) and would go on to parts in The House That Dripped Blood (1971) and The Wicker Man (1973), inhabits Countess Elisabeth so fully that it is impossible to imagine anyone else in the part; she also makes the most of a dramatic finale where she’s finally exposed before everyone for what she is. The fact that she’s dubbed is unfortunate, particularly given that her natural accent is perfectly matched for this role.

Nigel Green as the cynical Captain Dobi.

It’s true, as Pitt once complained, that the film does not go far enough in depicting the real-life horrors of Countess Báthory, settling instead on a possibly fictional account (blood bathing) and adding a supernatural element. There are opportunities here for more grisly goings-on, seeing as the real-life accounts have a touch of Ed Gein to them, or even shades of Nazism. (A plot-free alternative can be seen in the Báthory chapter of Walerian Borowczyk’s 1973 films Immoral Tales, which begins as an exercise in sensuality – a number of young women showering in the nude – before the Countess processes them through her factory to color her bathtub red. This film also uses vanity as its central theme; a more recent telling of this fairy tale could be Nicolas Winding Refn’s 2016 film The Neon Demon.) Regardless, the point is driven home, and the cruelty of the Countess’ dispatching of young women for her own purpose gains a chillingly aristocratic remove by having so much of the bloodletting take place off-screen; we only later discover, for example, the dead body of a gypsy girl (a sadly underutilized Nike Arrighi, who had starred in Hammer’s The Devil Rides Out). Hungarian-born director Peter Sasdy, whose Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970) is one of the most interesting and worthwhile Dracula films, is saving his blood for the “shock” of seeing the Countess in her bathtub for the first time – fully nude, dabbing herself with a giant blood-soaked sponge. It’s an iconic moment for Hammer, but the film itself deserves mention when pointing out that the studio, this late in its life, still delivered an impressive share of horror classics.