I usually don’t write capsule reviews on this site, but I’ve been away for too long while working on a different writing project (and now that I have a young son, writing time is more precious than ever). I’ve been on a 70’s British horror kick these last few weeks and any one of the below films would be worthy of more in-depth analysis than I’m going to provide here, but I thought it might be worth posting my brief thoughts nonetheless:

Asylum (1972)/–And Now the Screaming Starts! (1973)/The Beast Must Die (1974)

These three Amicus films were released over the holidays by Severin Films as a box set, bundled with a bonus disc of Amicus-themed extras (of those extras, so far I have only watched the hour-long reel of Amicus trailers, which was very entertaining). Although the announcement of this box set was greeted with enthusiasm from classic horror fans on both sides of the ocean, on release it’s taken a drubbing from those keenly studying the A/V quality. In particular, The Beast Must Die has been deemed by many to be “unwatchable”; at least one online comment claimed it is “worse than VHS,” but take it from somebody who has spent much of the winter transferring VHS tapes to digital: that’s irresponsible hyperbole. In fact, all three just look like old unrestored prints, though it’s true that The Beast Must Die is the weakest-looking of the three – with some scenes demonstrating real softness in the detail while other scenes, unaccountably, looking fine.

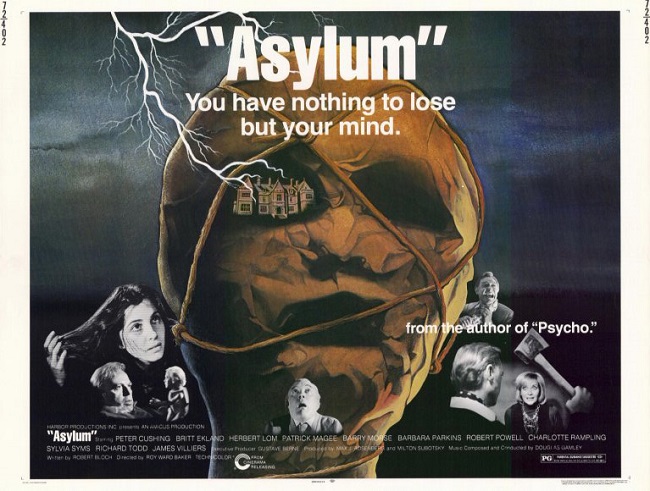

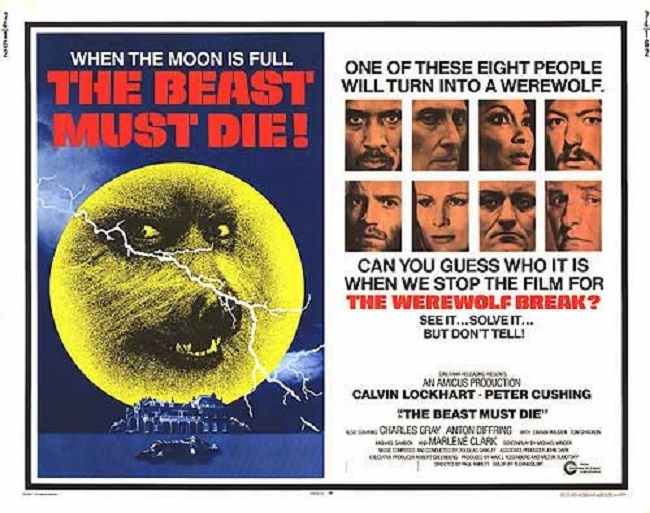

I split the box set over two nights, first watching Asylum and The Beast Must Die as a double feature, which was a good decision since the latter is truly a B-movie and should be watched as late into the night as possible. Asylum is regarded as one of Amicus’s best anthologies (they made a lot of them – see my next two reviews), and it’s easy to see why, since the stories here – by Amicus’s go-to horror writer, Robert Bloch – are all decent, and the linking material cleverly becomes the closing tale (“Mannikins of Horror,” with A Clockwork Orange’s Patrick Magee and Phantom of the Opera’s Herbert Lom). “Lucy Comes to Stay” is slight but benefits from performances by Britt Ekland (The Wicker Man) and Charlotte Rampling (right before The Night Porter). Best of the segments is the Peter Cushing one, unsurprisingly; he orders a suit tailor-made to occult specifications. The Beast Must Die has a William Castle gimmick that was ridiculously outdated by 1974: it’s a whodunit which stops the action pre-climax for a “Werewolf Break” to allow the audience a full minute to guess who the killer werewolf might be. (For the record, I guessed correctly, though there was a twist I didn’t see coming.) This is a wonderfully ridiculous “thriller” with some recognizable faces, including Cushing again and Charles Gray (The Devil Rides Out, Diamonds are Forever, The Rocky Horror Picture Show), though notably the lead role is given to the enigmatic Calvin Lockhart, black and born in the Bahamas, as a wealthy hunter who wants to add a werewolf to his trophy room.

I split the box set over two nights, first watching Asylum and The Beast Must Die as a double feature, which was a good decision since the latter is truly a B-movie and should be watched as late into the night as possible. Asylum is regarded as one of Amicus’s best anthologies (they made a lot of them – see my next two reviews), and it’s easy to see why, since the stories here – by Amicus’s go-to horror writer, Robert Bloch – are all decent, and the linking material cleverly becomes the closing tale (“Mannikins of Horror,” with A Clockwork Orange’s Patrick Magee and Phantom of the Opera’s Herbert Lom). “Lucy Comes to Stay” is slight but benefits from performances by Britt Ekland (The Wicker Man) and Charlotte Rampling (right before The Night Porter). Best of the segments is the Peter Cushing one, unsurprisingly; he orders a suit tailor-made to occult specifications. The Beast Must Die has a William Castle gimmick that was ridiculously outdated by 1974: it’s a whodunit which stops the action pre-climax for a “Werewolf Break” to allow the audience a full minute to guess who the killer werewolf might be. (For the record, I guessed correctly, though there was a twist I didn’t see coming.) This is a wonderfully ridiculous “thriller” with some recognizable faces, including Cushing again and Charles Gray (The Devil Rides Out, Diamonds are Forever, The Rocky Horror Picture Show), though notably the lead role is given to the enigmatic Calvin Lockhart, black and born in the Bahamas, as a wealthy hunter who wants to add a werewolf to his trophy room.

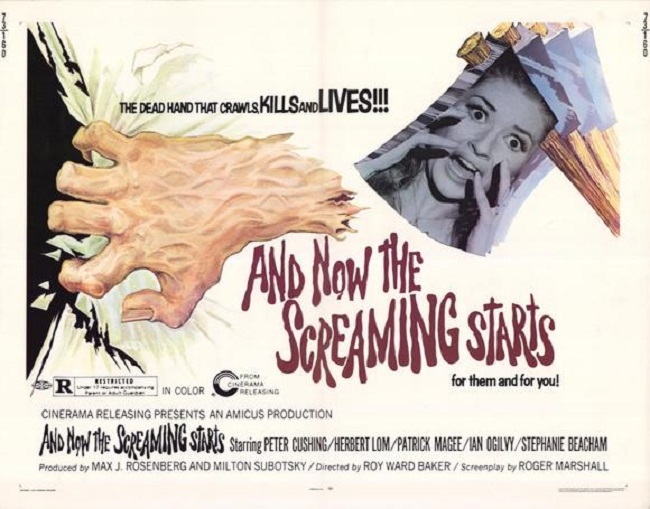

–And Now the Screaming Starts! (as it’s punctuated onscreen) is not, in fact, a sequel to the Amicus film Scream and Scream Again (1970). It’s a thriller that manages to accommodate ghosts living in old portraits like something in Disney’s Haunted Mansion ride, a crawling severed hand (a gadget that appears so often in Amicus films that it should get its own credit), an extended flashback revealing dark family secrets reminiscent of early Hammers The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959) and The Curse of the Werewolf (1961), Stephanie Beacham’s formidable décolletage, and more roles for Cushing, Magee, and Lom. In other words, it’s a Gothic hodgepodge, doesn’t quite hold together, and is shamelessly entertaining.

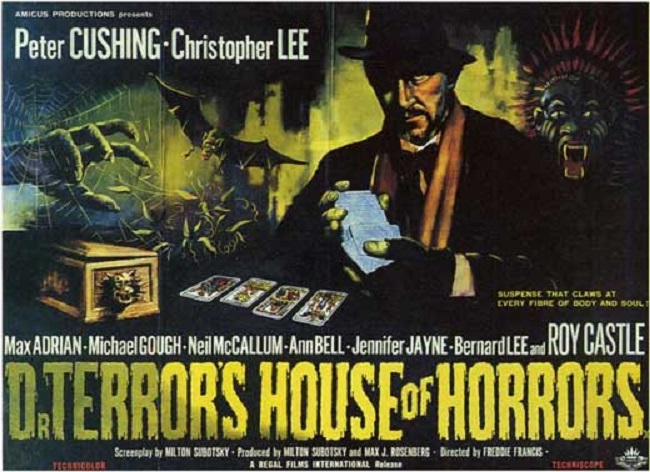

Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965)

To scratch more of my Amicus itch, I checked out the Olive Blu-ray release of the first anthology from “the studio that dripped blood,” Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors. The screenplay is by Amicus co-founder Milton Subotsky, whose enthusiasm for this genre was not matched by his writing ability, frankly. Nonetheless, this is one of my favorites of the studio’s films thanks to (a) the palpable atmosphere in the framing scenes, straight out of a Mario Bava film, and (b) the perfect cast. Academy Award-winning cinematographer-turned-horror director Freddie Francis helms this one (he became an Amicus standby), and the stories are linked by a Tarot card-wielding doctor (Cushing) who reveals the fates of his increasingly alarmed fellow passengers. The cast includes Christopher Lee, Michael Gough, Donald Sutherland, musician/comedian Roy Castle, Bernard Lee, Neil McCallum, and Isla Blair. Granted, the segments are rudimentary and feel like the beginning of a good tale rather than its entirety (you may find yourself saying more than once, “Wait, that’s it?”), but highlights include a Triffid-like story of a murderous vine, a creepy, high-energy segment involving jazz and voodoo, a surprisingly brutal vampire yarn with Sutherland, and Lee battling that familiar old severed hand.

From Beyond the Grave (1974)

This, the last of the Amicus anthologies, is truly special; it was the first time I’d seen it (I recorded it off TCM last year), and it’s clearly one of the strongest, if not the strongest, portmanteau film they ever did. The stories this time are based on the work of R. Chetwynd-Hayes, and are strung together by Cushing’s antique shopkeeper, who might as well be Dr. Terror in retirement. The antiques themselves become the stars of each story, the best of which is an almost devastating tale of an unhappily married middle-aged war vet (Ian Bannen) whose connection with another vet (Donald Pleasence) whom he passes on the street leads to an invite to a comically awkward dinner and a gradual obsession with the man’s eerily detached daughter (played by Pleasence’s real-life daughter Angela, who is superb). The young woman’s unquestioning willingness to serve the henpecked, sexually frustrated Bannen strips away at his British middle-class complacency, passive-aggression, and general worry of making too much a scene until his destructive, sublimated desires are revealed. Other stories include evocative tales of portals to ghostly dimensions – one an ornate door which, when installed, opens to a mysterious blue room; another a mirror whose dead occupant drives David Warner to slasher-style murders – and a lighter tale of domestic exorcism by means of a very eccentric medium (years before Poltergeist). Highly recommended!

Horror of Frankenstein (1970)

Horror of Frankenstein (1970)

Loathed among most Hammer fans, this reboot of the studio’s Frankenstein series (decades before anyone would use that term) sets Cushing aside for a tale of a young Victor Frankenstein, introduced being called out in front of the class for drawing surgical dotted-lines through a nude etching. The brilliant young man is now played by Ralph Bates, whom Hammer was grooming to be its newest horror star (see: Taste the Blood of Dracula). Written and directed by Jimmy Sangster, who wrote Hammer’s original Curse of Frankenstein (1957) – an odd choice to provide a fresh new take on the series, to be sure – the key difference here is that the film is played as a black comedy. The monster, as crudely rendered by future Darth Vader David Prowse, is almost an afterthought, not appearing until two-thirds of the way into the picture. Instead, the plot focuses on Frankenstein’s scheming for the freedom to conduct his experiments, which leads him not only to murder, but a bona fide killing spree; he even takes the castle housekeeper (Kate O’Mara) into his bed to literally take the place of his father (who also bedded her). Veronica Carlson, who had, oddly, just appeared in the most recent entry of the main Frankenstein series, here is relegated to a thankless role fawning after Frankenstein, and Jon Finch (Frenzy, Macbeth) makes a welcome addition to the supporting cast, though he isn’t given much to do, either.

The film is actually rich with witty dialogue, though how much you laugh depends on how receptive you are to Sangster’s (very) black humor. The film is so aligned with its callous antihero that the satire might fairly be called mean-spirited. More unfairly, many critics, focusing on a single brief scene in which Frankenstein makes a severed hand give a rude gesture, have inaccurately called the film’s humor juvenile. But the real problem here is the third act. Having propped up Frankenstein as a man who never loses, the introduction of the creature should set up a comic catastrophe of everything going wrong for him: I want to see Bates scrambling to cover up a massacre, flustered and desperate as his creature goes on the rampage. This would justify all the time spent establishing the doctor as something of a master criminal, and imagine what a showcase that would be for Bates, who is very good in this film regardless. Instead, the doctor’s only comeuppance comes in the film’s final gag – and it’s nothing more than a mild setback before he resumes his experiments. It would take Young Frankenstein to fulfill the potential of sending up the old Gothic laboratories.

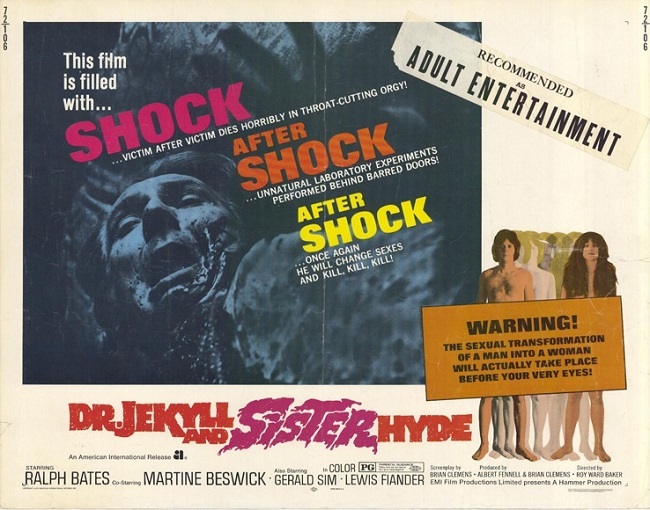

Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971)

Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971)

A year later, Hammer tried something different for Bates: a more sympathetic role (though he’d still commit murders willy-nilly), and a more interesting screenplay, this coming from Brian Clemens of the Avengers TV series (and soon to write Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter for Hammer). Bates’s Dr. Jekyll takes his potion to become Martine Beswick’s Mrs. Hyde, and the best part of the film is this uncanny casting decision; they truly look like they came from the same gene pool. Tasked with coming up with a script to flesh out the tossed-out joke of a title, Clemens further indulges by including Burke & Hare and Jack the Ripper (Jekyll/Hyde, in this case, are the Ripper), and Jekyll’s search for eternal youth echoes Dorian Gray. Beswick chews the scenery nicely, and Clemens generates some real drama (and welcome humor) as Jekyll’s experiments catch the interest of the upstairs neighbors, a brother and sister who are attracted to Hyde and Jekyll, respectively. The sexual confusion leads to some intriguing, and surprisingly forward-thinking, comments about gender fluidity. But it also leads to narrative and thematic confusion, as both Jekyll and Hyde are killers, thus dampening the point of the transformation from the original novel. (The quest for immortality, through injecting female hormones, also doesn’t land because we don’t really see Jekyll benefiting in that regard. The killings don’t feel like they have any real impetus.) Unfortunately, the film is also too long, and drags terribly in its third act, despite a visually impressive chase along London rooftops. If this concept is “so crazy it just might work”…well, it almost does.

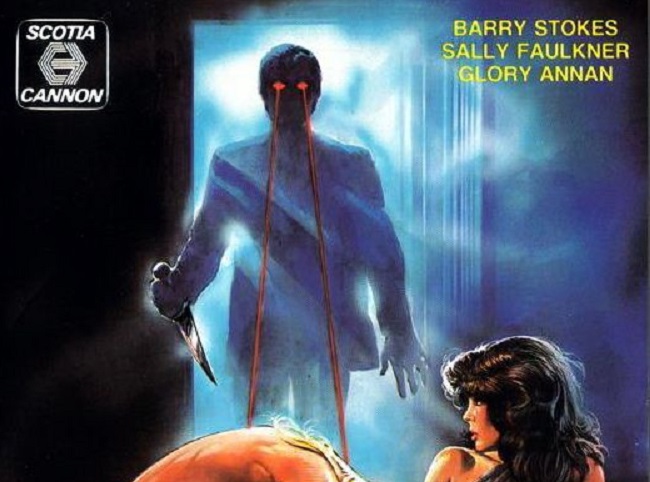

Prey (1977)

Prey (1977)

Norman J. Warren (Satan’s Slave) directed this offbeat British film, a thematically rich science fiction/horror hybrid, now available on Blu-ray from Vinegar Syndrome. The concept is essentially a tale of “the fox in the hen-house”: a carnivorous, shapeshifting alien (Barry Stokes), whose true form resembles a fox with rows of sharp teeth, infiltrates the domestic bliss of a lesbian couple in the secluded country: a young Canadian woman (Glory Annen) and her older, jealous companion (Sally Faulkner). The longer the stranger remains in their presence, the more erratic Faulkner behaves, distraught at the slaughter of her chickens (which is blamed on a fox), furious that she might lose the affections of Annen to this odd young man, and slowly suspecting that he might not be what he seems.

Prey, produced on a paltry budget during the British film industry’s lowest ebb, wears its art house pretentions on its sleeve, from rendering the alien’s transformations through Godardian jump cuts to a private party in which the women dress their male guest in a black slip and adorn his face with makeup, and finally to a most bizarre, interminable slow-motion scene of all three thrashing about in a muddy pond while electronic music thrums on the soundtrack. Undermining all this are not the exploitation-ready sex scenes or flesh-eating gore, but rather the absurd contradiction that the alien, who speaks in broken English and doesn’t understand common words like “swim,” can speak in casually perfect English when communicating in secret with his (also British) fellow E.T.’s via a radio. (This leads to a very silly final line, which makes one think that Warren wasn’t aiming for the art house, but for Twilight Zone parody.) This one’s a big miss, though it’s undoubtedly an interesting one.