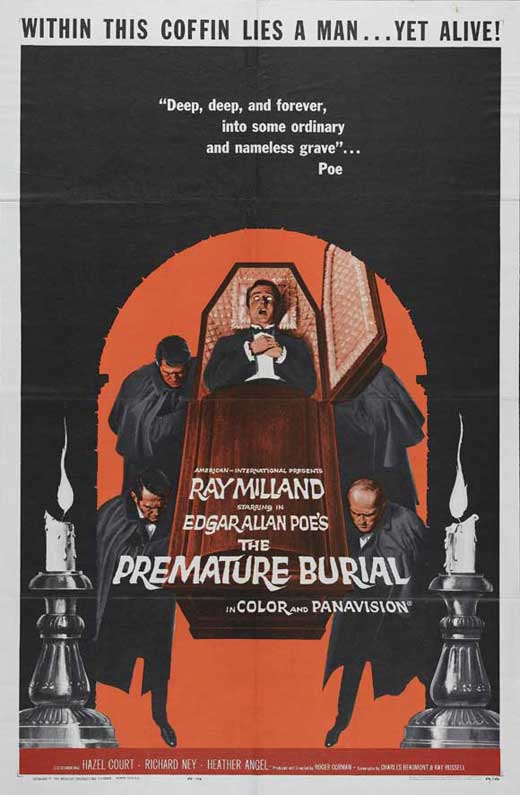

On the Kino Blu-ray of The Premature Burial (1962), there’s an entertaining interview with Joe Dante in which he recalls that Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe series brought the kids out to the cinema not just because they were reliably quality horror films, but because it was Poe: that one writer you studied in school whose work seemed unwholesome for the classroom. These films profited from walking that fine line, with a literary veneer and pedigree (though sometimes just the Poe title would be used) stretched thinly over Gothic excess, Corman’s trademark psychedelic dream sequences, the occasional suggestion of necrophilia, shamelessly recycled footage, and campier touches of the macabre. The Premature Burial was the third of these films, following the very successful The Fall of the House of Usher (aka House of Usher, 1960) and The Pit and the Pendulum (1961). What makes it stand out is that Vincent Price, the series’ star, is nowhere to be found. After a dispute with American International Pictures over distribution of profits, Corman decided to go it alone with a modest budget provided by Pathé Labs. This meant that Price, under contract with AIP, was off limits, so Corman sought out another Hollywood star, the distinguished Ray Milland (Dial M for Murder, The Lost Weekend), to play the central role of Guy Carrell, whose greatest fear is being buried alive. Milland was a few years older than Price and brought a distinctly different presence: a Cary Grant-like combination of British dignity and detached charm. As Price returned again and again to his Gothic horror roles, it became easier in each film to chart all the waypoints in his descent into psychosis or sadism; with Milland, his third-act turn from haunted shell into angel of vengeance feels genuinely surprising, and he’s clearly having fun in the role. Ironically, AIP purchased Pathé just as production was getting started, and so this might have been a Price picture all along; but instead it becomes one of the more unique entries in the Poe cycle.

On the Kino Blu-ray of The Premature Burial (1962), there’s an entertaining interview with Joe Dante in which he recalls that Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe series brought the kids out to the cinema not just because they were reliably quality horror films, but because it was Poe: that one writer you studied in school whose work seemed unwholesome for the classroom. These films profited from walking that fine line, with a literary veneer and pedigree (though sometimes just the Poe title would be used) stretched thinly over Gothic excess, Corman’s trademark psychedelic dream sequences, the occasional suggestion of necrophilia, shamelessly recycled footage, and campier touches of the macabre. The Premature Burial was the third of these films, following the very successful The Fall of the House of Usher (aka House of Usher, 1960) and The Pit and the Pendulum (1961). What makes it stand out is that Vincent Price, the series’ star, is nowhere to be found. After a dispute with American International Pictures over distribution of profits, Corman decided to go it alone with a modest budget provided by Pathé Labs. This meant that Price, under contract with AIP, was off limits, so Corman sought out another Hollywood star, the distinguished Ray Milland (Dial M for Murder, The Lost Weekend), to play the central role of Guy Carrell, whose greatest fear is being buried alive. Milland was a few years older than Price and brought a distinctly different presence: a Cary Grant-like combination of British dignity and detached charm. As Price returned again and again to his Gothic horror roles, it became easier in each film to chart all the waypoints in his descent into psychosis or sadism; with Milland, his third-act turn from haunted shell into angel of vengeance feels genuinely surprising, and he’s clearly having fun in the role. Ironically, AIP purchased Pathé just as production was getting started, and so this might have been a Price picture all along; but instead it becomes one of the more unique entries in the Poe cycle.

Guy Carrell (Ray Milland) and his wife Emily (Hazel Court) confront his darkest fears.

As with the other films in the series, The Premature Burial is not set in anything resembling reality. Guy Carrell’s manor is surrounded not just by a dark forest out of fairy tales but tombstones and a monolithic mausoleum, all of it forever blanketed in fog. It’s Hollywood Gothic, and by necessity disguises the limited sets (as in many of Corman’s other films, notably 1957’s The Undead). Similarly, Carrell’s descent into mania, spurred by his obsession with his belief that his father was buried alive after a cataleptic fit rendered him paralyzed – and his certainty that the same fate awaits him – leads to a scene which is both deliriously wonderful and completely absurd. Having spent long hours away from his new wife Emily (The Curse of Frankenstein’s Hazel Court, transitioning from British horror roles into a Hollywood career), Guy proudly showcases the modifications he’s made to the family mausoleum. It brings to mind one of James Bond’s visits to Q’s workshop. In case of premature burial, Carrell will now have a trigger mechanism to open his coffin at all angles (we can also see that he has attached tools to the lid to pry his way out if the trigger malfunctions); he also has numerous methods to break free of the building including a rope ladder that drops from the ceiling and a secret passage. But should all else fail, he’s prepared a goblet of poison to allow a peaceful demise. Appropriately, Emily and their friend Miles Archer (Richard Ney) look at him as though he’s gone completely insane. Corman works this tricked-out tomb into a surreal dream in which Carrell is buried alive and can’t get free, leading him inexorably to that goblet of poison – which is filled with teeming worms. (At one point, the “Conqueror Worm” of death is invoked in the dialogue, a reference to a Poe poem which would later become the U.S. title of Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General.)

Carrell, still alive, is lowered into his grave.

The film’s true tour de force scene is more subtle. Haunted by the tune “Molly Malone,” which he gradually realizes was whistled by one of the gravediggers at his father’s burial, he is pursued into an abandoned room by the melody; just as it seems to go silent, the wind takes up a “Molly Malone” whistle. When he goes to shut the window, one of the gravediggers is standing there, leering horribly at him – an Innocents-style shock that packs a real jolt. (Incidentally, the gravediggers are played by well-traveled character actors John Dierkes and Dick Miller, the latter’s presence being a given.) Despite entertaining scenes such as these, The Premature Burial drags for a long while because we know where it’s going – we’ve read the title. Milland can also seem one-note, not through any fault in his performance, but because he’s a typical Poe protagonist, morbidly, suffocatingly obsessed; there’s a feeling of marking time until the finale. But then dream-team screenwriters Charles Beaumont (who wrote some of the best episodes of The Twilight Zone) and Ray Russell (writer of the classic horror tale “Sardonicus”) pull a third-act twist that makes the whole enterprise worthwhile. As expected, Milland succumbs to catalepsy, is mistaken for dead, and sealed in a coffin; worse still, he had taken his wife’s advice and destroyed his precious mausoleum, and is thus buried with no means of escape. But his much-loathed gravediggers actually free him, and he’s transformed into a hollow-eyed figure of Death, obsessed with revenge, having realized that his wife has actually been plotting his destruction from the start. Though one might predict this in the Diabolique-style thrillers that William Castle and Hammer’s Jimmy Sangster were crafting in the early 60’s, it’s a bit more unexpected in a Corman Poe Gothic, and gives a delightfully bloodthirsty energy to the climactic scenes of electrocution – Milland giving a sinister grin as he flips a switch – and a second premature burial, one with the coffin still open (poor Hazel Court and her mouthful of dirt!). This film, lacking Price, has been treated as the ugly duckling of the series, but Milland nonetheless infuses the familiar decrepit atmosphere with an admirably committed performance, making The Premature Burial worth a second look. Price fans, at any rate, didn’t have to wait long – the superb Poe anthology Tales of Terror was released the same year.