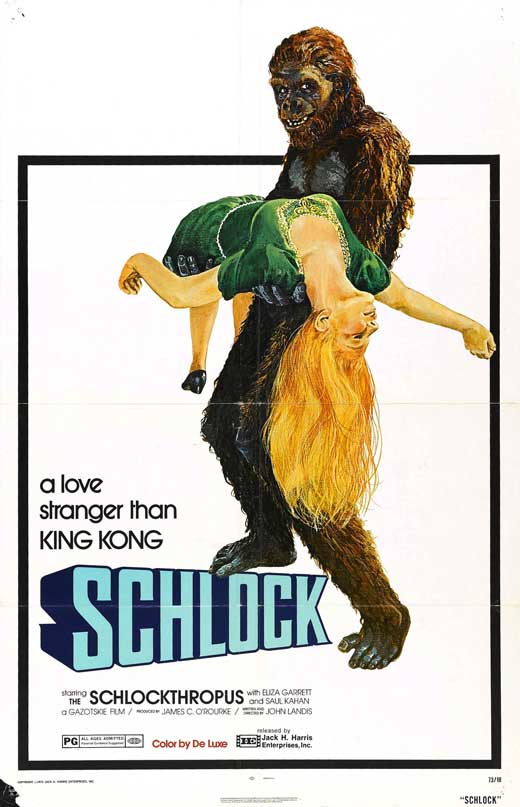

Having bounced around Hollywood for a few years as an extra, a stuntman, or in any capacity that studios would hire him, a lanky, long-haired, 21-year-old John Landis lost patience waiting for opportunities to direct – so he made a film himself. Ostensibly inspired by the terrible Trog (1970), in which Joan Crawford obsesses over a troglodyte, his Schlock (1973) marked a number of firsts in a filmography tied together by running gags, in-jokes, and familiar faces. It was his first mention of “See You Next Wednesday,” a non-existent film whose title is taken from a random line of dialogue in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). It was his first use of a man in an ape suit – here played by Landis himself. It was the first expression of his particular sense of humor: a little lowbrow, a little slapstick, more than a little anarchic. It was his first collaboration with Rick Baker, a makeup artist still living in his parents’ house when Landis hired him to make a primate costume on the cheap. The result, incidentally, was of a higher quality than Schlock deserved or even intended. Landis wanted a monster that looked hokey but which the characters took seriously – that was the gag. Baker, hungry and talented, was shooting for something that would live up to 2001‘s opening sequence, to suit the film’s many references to Kubrick’s masterpiece (for crying out loud, even “Heywood Floyd,” the character played by William Sylvester, gets a shout-out). Several years later, Baker would be winning the Academy Award for Best Makeup on An American Werewolf in London (1982), the film Landis had been waiting to make since he wrote it as a teenager.

Having bounced around Hollywood for a few years as an extra, a stuntman, or in any capacity that studios would hire him, a lanky, long-haired, 21-year-old John Landis lost patience waiting for opportunities to direct – so he made a film himself. Ostensibly inspired by the terrible Trog (1970), in which Joan Crawford obsesses over a troglodyte, his Schlock (1973) marked a number of firsts in a filmography tied together by running gags, in-jokes, and familiar faces. It was his first mention of “See You Next Wednesday,” a non-existent film whose title is taken from a random line of dialogue in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). It was his first use of a man in an ape suit – here played by Landis himself. It was the first expression of his particular sense of humor: a little lowbrow, a little slapstick, more than a little anarchic. It was his first collaboration with Rick Baker, a makeup artist still living in his parents’ house when Landis hired him to make a primate costume on the cheap. The result, incidentally, was of a higher quality than Schlock deserved or even intended. Landis wanted a monster that looked hokey but which the characters took seriously – that was the gag. Baker, hungry and talented, was shooting for something that would live up to 2001‘s opening sequence, to suit the film’s many references to Kubrick’s masterpiece (for crying out loud, even “Heywood Floyd,” the character played by William Sylvester, gets a shout-out). Several years later, Baker would be winning the Academy Award for Best Makeup on An American Werewolf in London (1982), the film Landis had been waiting to make since he wrote it as a teenager.

A typical Schlock gag that anticipates The Kentucky Fried Movie.

In its best moments – really, the hysterical first half – Schlock feels like a warm-up to one Landis movie in particular, The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), his collaboration with collegiate sketch comedy troupe the Kentucky Fried Theater, whose members (David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, and Jim Abrahams) would go on to write and direct Airplane! (1980). And though the film’s PG rating takes some of the edge off, the film’s absurdist caricature of the world is in line with Doug Kenney and the National Lampoon, whom he’d work with on his breakout hit, Animal House (1978). But all that was in the future, and Landis still had lessons to learn: some quite fundamental lessons in film grammar and how to shoot what you’ll need for the editing room. He had to teach himself by making Schlock. What this means is that the film is choppy as hell, sometimes losing the proper pacing for a joke to really land. Other scenes, particularly in the second half, just drag without a worthwhile payoff. Yet even these moments often contain sparks of comic inspiration that he’d learn to use more efficiently in films to come: deadpan extras, meandering whimsy, gags like the scribbles in the corners of MAD Magazine comic strip panels. The plot of Schlock ain’t much, by design. An unknown killer has been leaving behind a mountain of dead bodies, his calling card banana peels. A baffled police detective, Sgt. Wino (Saul Kahan, Into the Night), his dim-witted fellow officers, and an unusually cheerful news reporter for a local TV station pursue the clues to a cave where lurks the missing link called the Schlockthropus (Landis). Schlock, as they call him, escapes the authorities and heads deep into suburbia (like one Eegah before him), where he becomes infatuated with a blind teenager named Mindy (Eliza Garrett, Animal House, and the future Mrs. Eric Roberts). Mindy thinks the affectionate furry creature is just a stray dog, but when her eyesight is restored through surgery, she’s horrified by Schlock. He proceeds to raid her prom and abduct her before the National Guard is called in to stop him.

Schlock performs a piano duet with Ian Kranitz.

Re-released much later as The Banana Monster, Schlock works best when it tosses out its beautifully dumb jokes in rapid succession. After the reporter notes that some of the victims have been torn into such small pieces that the police haven’t identified how many bodies they belong to yet, he promptly launches a contest inviting viewers to guess how many bodies are in the body bags. When Mindy’s boyfriend hands her a gift, it’s a copy of the (sadly very real) book Ann Landers Talks to Teenagers About Sex. A bandage-removing scene after Mindy’s surgery is hilariously interminable, briefly cutting to the floor, where the bandages are now piling up to her thighs. And a splendid little digression follows a group of teens into Schlock’s cave, with Landis’ script nailing the idiotic dialogue of the kinds of youths who usually wander through monster movies. (When one teen comes across the ape actively pounding his friend into mush, he raises a finger and says, “Hey, have you seen–?” before meeting his inevitable end.) Landis is on shakier ground when he gets lost in his homages: an accurate recreation of the “Also Sprach Zarathustra” scene in 2001 doesn’t go anywhere all that clever; at one point Schlock encounters a girl feeding ducks and we suspect he’s going to throw her into the water a la Frankenstein, though to no end (or gag); and a scene in a movie theater is padded with too many long clips from The Blob (1958) and Dinosaurus! (1960), though admittedly the entire scene actually was added to pad out the film to a more feature-worthy running time. Yet even these bits offer something to make you smile, such as when Schlock, finally settled in to watch his double-feature, feels a tug at his side. A little boy whispers into his ear. Nodding, Schlock stands up and patiently leads him to the restroom. Sublime.