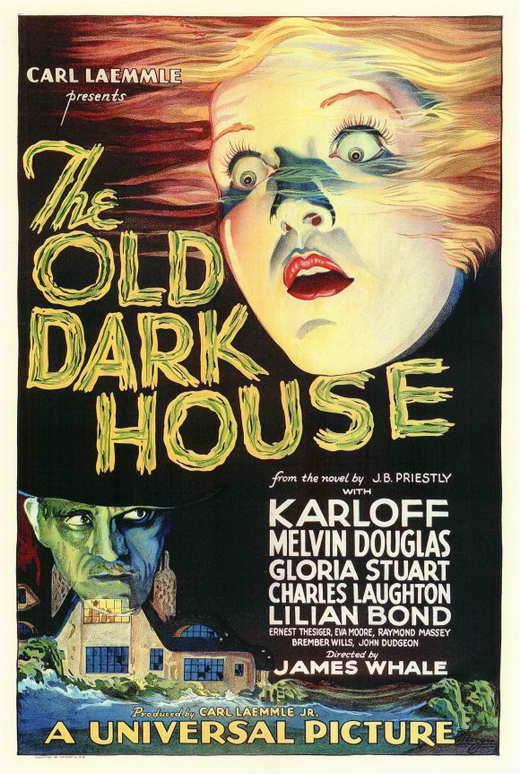

Dismissed on these shores in its day, James Whale’s follow-up to Frankenstein (1931), The Old Dark House (1932), is something of a wonder with its graceful balance of comedy, romance, and a light dash of terror. Adapting the 1927 novel Benighted by the innovative British author J.B. Priestley, Whale serves up a cavernous manor that seems to exist in another plane of reality, haunted only by its dangerously eccentric inhabitants, the Femms. Three travelers come stumbling across this family’s demented legacy: Philip Waverton (Raymond Massey, A Matter of Life and Death), his wife Margaret (Gloria Stuart, Titanic), and their bachelor friend Roger Penderel (Melvyn Douglas, Ninotchka). Driving through muddy roads in the middle of a torrential downpour, and climbing a hill surrounded by encroaching floodwaters, they have no choice but to seek shelter at the Femm place, where they’re immediately greeted by the shadow-draped features of Boris Karloff, playing the “dumb” and perpetually gibbering servant Morgan. Only slightly more welcoming is Horace Femm (Ernest Thesiger, later to appear as Dr. Pretorius in Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein) – who nonetheless urges them to leave. His raving sister Rebecca (Eva Moore) is even more vociferous in her objections, and if nothing the guests can say will dissuade her, it’s because she can’t hear them – she’s mostly deaf. But Philip, Margaret, and Roger have nowhere to go. Soon they’re joined by two more souls stranded by the storm, the wealthy Sir William Porterhouse (Charles Laughton, who made Island of Lost Souls the same year) and his showgirl companion Gladys (Lilian Bond). Over the course of this dark and stormy night, the guests uncover secrets, and more unhinged Femms, while the wind and rain lash at the windows.

Dismissed on these shores in its day, James Whale’s follow-up to Frankenstein (1931), The Old Dark House (1932), is something of a wonder with its graceful balance of comedy, romance, and a light dash of terror. Adapting the 1927 novel Benighted by the innovative British author J.B. Priestley, Whale serves up a cavernous manor that seems to exist in another plane of reality, haunted only by its dangerously eccentric inhabitants, the Femms. Three travelers come stumbling across this family’s demented legacy: Philip Waverton (Raymond Massey, A Matter of Life and Death), his wife Margaret (Gloria Stuart, Titanic), and their bachelor friend Roger Penderel (Melvyn Douglas, Ninotchka). Driving through muddy roads in the middle of a torrential downpour, and climbing a hill surrounded by encroaching floodwaters, they have no choice but to seek shelter at the Femm place, where they’re immediately greeted by the shadow-draped features of Boris Karloff, playing the “dumb” and perpetually gibbering servant Morgan. Only slightly more welcoming is Horace Femm (Ernest Thesiger, later to appear as Dr. Pretorius in Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein) – who nonetheless urges them to leave. His raving sister Rebecca (Eva Moore) is even more vociferous in her objections, and if nothing the guests can say will dissuade her, it’s because she can’t hear them – she’s mostly deaf. But Philip, Margaret, and Roger have nowhere to go. Soon they’re joined by two more souls stranded by the storm, the wealthy Sir William Porterhouse (Charles Laughton, who made Island of Lost Souls the same year) and his showgirl companion Gladys (Lilian Bond). Over the course of this dark and stormy night, the guests uncover secrets, and more unhinged Femms, while the wind and rain lash at the windows.

While The Old Dark House belongs to the subgenre with which it shares its name, it also self-consciously spoofs it. This wasn’t unique in and of itself; thrillers with Gothic trappings that combined spooky mystery with light comedy dated back to the Silent era and were popular on the stage, the notable example being Mary Roberts Rinehart and Avery Hopwood’s 1920 play The Bat, which was adapted for the screen three times. Throughout the 30’s, common features of what we might call horror films were sleepovers in isolated manors, gloomy butlers, swinging shutters and slamming doors, secret doors behind bookshelves, and a barely-glimpsed supernatural villain typically exposed to be quite human. (Decades later, Scooby-Doo would make this the show’s whole shtick.) Even by 1932, the premise of The Old Dark House would be very familiar to audiences, if they weren’t exhausted by it already. Yet Whale handles the material with sly class. What you won’t find here are jarring comic relief characters, though all of the Femms are amusing in various ways; none of the guests exists to bug out their eyes and run screaming from menacing groping hands (though a disembodied hand does make a significant appearance). Whale doesn’t resort to masked phantoms or a convoluted plot. He simply lets the characters’ actions dictate the comedy, romance, and suspense – all of which, I should add, are charming to the extreme. Freed from the more tedious conventions of the subgenre, The Old Dark House has aged like fine wine. (Its recent restoration is available on Blu-ray.)

While The Old Dark House belongs to the subgenre with which it shares its name, it also self-consciously spoofs it. This wasn’t unique in and of itself; thrillers with Gothic trappings that combined spooky mystery with light comedy dated back to the Silent era and were popular on the stage, the notable example being Mary Roberts Rinehart and Avery Hopwood’s 1920 play The Bat, which was adapted for the screen three times. Throughout the 30’s, common features of what we might call horror films were sleepovers in isolated manors, gloomy butlers, swinging shutters and slamming doors, secret doors behind bookshelves, and a barely-glimpsed supernatural villain typically exposed to be quite human. (Decades later, Scooby-Doo would make this the show’s whole shtick.) Even by 1932, the premise of The Old Dark House would be very familiar to audiences, if they weren’t exhausted by it already. Yet Whale handles the material with sly class. What you won’t find here are jarring comic relief characters, though all of the Femms are amusing in various ways; none of the guests exists to bug out their eyes and run screaming from menacing groping hands (though a disembodied hand does make a significant appearance). Whale doesn’t resort to masked phantoms or a convoluted plot. He simply lets the characters’ actions dictate the comedy, romance, and suspense – all of which, I should add, are charming to the extreme. Freed from the more tedious conventions of the subgenre, The Old Dark House has aged like fine wine. (Its recent restoration is available on Blu-ray.)

Ernest Thesiger

Whale’s handling of character has so much to do with the film’s endearing qualities. Each member of the Femm clan chews scenery to escalating degrees directly proportional to how high up in the Femm House they’re stationed. In the furthest climes we encounter the bedridden, 102-year-old Sir Roderick Femm, who, despite all the whiskers, is played by a woman (Elspeth Dudgeon). And behind a locked door is the pyromaniac Saul (Brember Wills), whose confrontation with Roger perfectly embodies the film as a whole. As a knife-wielding Saul and a nervous Roger shift seats around an elongated dinner table, it’s a joy to watch Whale’s elegantly choreographed tension and humor, in which body movements are just as important – and telling – as the dialogue. Karloff (billed only as KARLOFF) has no dialogue but plenty to do as an agent of chaos who continually keeps the guests on their toes. It’s possible to get lost in the suspense and ignore the comic aspects altogether; Whale lets you choose, but the comedy is organically present. Though The Old Dark House could easily be read as a send-up, it understands that it must also deliver on what this genre demands.

Lilian Bond

The guests, stuck with this mad household for a night, are, remarkably, all likable individuals, though perhaps Massey gets the least to do. Stuart, who in the following year would appear in another Universal classic, the Whale-directed The Invisible Man, provides the Pre-Code sex appeal (stripping down to a skimpy slip almost as soon as she arrives); Douglas, meanwhile, gets a romance subplot with Bond and a big fight scene in the climax. Bond is hugely appealing as Gladys, who hesitantly confesses to her showgirl background and quickly falls for Roger while taking cozy shelter in the garage. Another sign that this is Pre-Code: her direct admission that she and Laughton’s Porterhouse don’t have sex, but take solace in each other’s friendship and emotional comfort. Though a modern viewer might think that’s a bit too convenient, allowing a quick pair-up for Roger and Gladys, in effect it contributes to Whale’s and Priestley’s empathetic worldview. Sir Porterhouse is defined not as a stuffy and two-dimensional cuckold but as a widower still suffering from the loss of his greatest love; and when he learns that his friend has fallen for someone, his resentment begins to melt into understanding, even (by the film’s end) shared happiness. Not many genre films offer this kind of warmth in such a cold Gothic setting. The film is a small treasure.