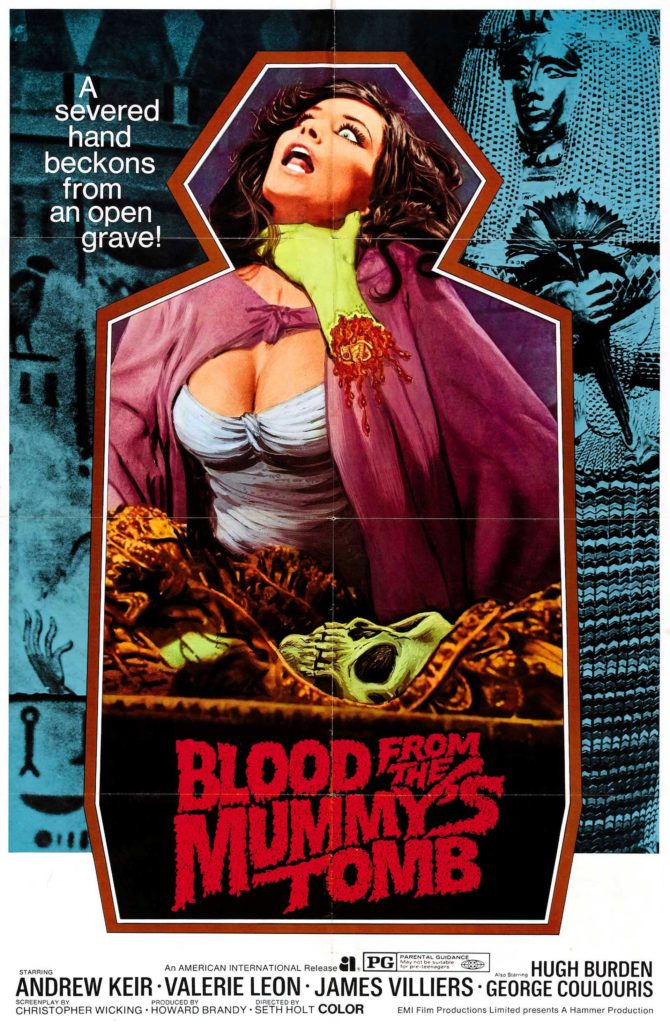

Hammer’s Mummy series, unlike its Frankensteins and Draculas, offered no continuity between installments, which were released only sporadically. Following Terence Fisher’s The Mummy (1959), which capped a classic Peter Cushing/Christopher Lee monster trilogy that began with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), Hammer gave us two fairly conventional Mummy romps, The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb (1964), directed by Michael Carreras, and The Mummy’s Shroud (1967), directed by John Gilling (The Plague of the Zombies). Carreras was the son of Hammer founder James Carreras, and despite ambitions earlier in his career to pursue non-horror filmmaking as a producer (he founded his own production company), he would come to produce and/or direct many films for Hammer, ultimately taking the reins of the ailing house of horror in 1972 after his father attempted to sell the company. Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971), produced and completed by Carreras after the untimely death of director Seth Holt during production, was the franchise’s final Mummy film, and if not the best, it’s at least the most curious of the bunch.

Hammer’s Mummy series, unlike its Frankensteins and Draculas, offered no continuity between installments, which were released only sporadically. Following Terence Fisher’s The Mummy (1959), which capped a classic Peter Cushing/Christopher Lee monster trilogy that began with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), Hammer gave us two fairly conventional Mummy romps, The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb (1964), directed by Michael Carreras, and The Mummy’s Shroud (1967), directed by John Gilling (The Plague of the Zombies). Carreras was the son of Hammer founder James Carreras, and despite ambitions earlier in his career to pursue non-horror filmmaking as a producer (he founded his own production company), he would come to produce and/or direct many films for Hammer, ultimately taking the reins of the ailing house of horror in 1972 after his father attempted to sell the company. Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971), produced and completed by Carreras after the untimely death of director Seth Holt during production, was the franchise’s final Mummy film, and if not the best, it’s at least the most curious of the bunch.

Andrew Keir, Mark Edwards (as “Tod Browning”) and Valerie Leon

The film dropped amidst a flood of lower-budgeted Hammer productions in the early 70’s, many of them indulging the looser British censorship restrictions, but several taking risks in style and plot that stretched the format of the Hammer Gothic. This was a period that saw the studio produce the likes of Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971) and Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter (1974), both written by Brian Clemens, as well as Peter Collinson’s searing psychological thriller Straight on Till Morning (1972), which resembled nothing Hammer had done to date. (The less said about Hammer’s big-screen adaptations of British sitcoms, the better.) Though with a title like Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb you might expect another “beware the beat of the cloth-wrapped feet” sort of film, the production positioned itself for something much more promising by choosing to adapt Bram Stoker’s novella The Jewel of the Seven Stars (1903). In the decades before Karloff wore the tattered bandages, Stoker wrote this story about the attempt by British archaeologists to resurrect an Egyptian mummy, the sinister Queen Tera. The novella is all about atmosphere, occult curiosity, and rising dread. There’s also the animated severed hand of the mummy, which is useful material for a horror movie. And yet the story had lacked a proper feature adaptation, exempting an episode of ITV’s Mystery and Imagination from 1970, bearing the undistinguished title “The Curse of the Mummy.” For Hammer to tackle a more unconventional kind of mummy story was exciting.

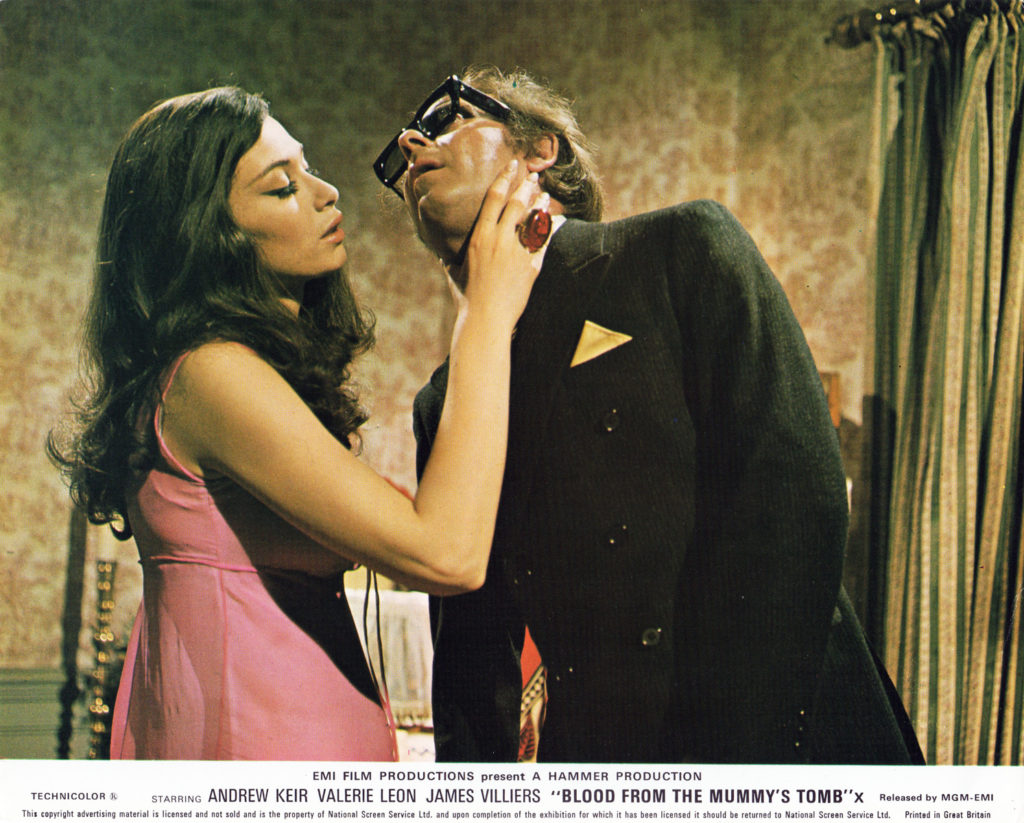

Leon, under Queen Tera’s influence.

Even more exciting that it should come from director Holt, who had made two of Hammer’s classiest black-and-white chillers, Taste of Fear (aka Scream of Fear, 1961) and The Nanny (1965). But the production seemed as cursed as the raiding of a tomb. First Peter Cushing, cast as the obsessed but fundamentally good archaeologist Julian Fuchs, left after a single day’s filming to care for his ailing wife. Then, as mentioned, Holt himself passed away suddenly – collapsing on set from heart failure. Carreras completed the work, but after reviewing Holt’s footage had to reshoot some sequences to properly edit the film together. Perhaps this is why the film has such a strangely disjointed feel. But it is also too languorous in its pacing. I can’t help but wonder if Holt hadn’t filmed some shots because he wanted to edit it together more tightly than Carreras’ more conventional style – but this is just speculation. I’ve seen Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb several times, and even at 94 minutes it drags. To the film’s credit, it maintains a dream-like feel, rich with Gothic atmosphere and a decorous score by Tristram Cary, but those attributes can also lull you to sleep if you’re not in the right frame of mind.

Leon explores her father’s unusual cellar.

What should be holding your attention is Valerie Leon, the buxom pin-up model who had appeared in bit parts in several films, here graduating to leading lady – and in a dual role no less! As the perfectly-preserved Queen Tera she doesn’t need to do much more than lie in (lush) state, but she does get a beautifully shot flashback sequence in which her hand is bloodily severed. As Margaret, Fuchs’ daughter born while he and his fellow tomb raiders uncovered Tera’s sarcophagus, she has the thankless task of portraying the film’s protagonist while remaining something of a mystery to the viewer. We see that she falls under the pall of Fuchs’ old partner Corbeck (an excellent James Villiers, who had appeared in The Nanny), plotting to resurrect Tera. And while wearing her ring (which contains the “seven stars” within its gemstone), she slowly becomes possessed by Tera’s power-hungry personality. Eventually – finally – a body count emerges, but Christopher Wicking’s script takes its time. That’s admirable, though it doesn’t make the plot terribly compelling. Filling in for Cushing is Andrew Keir (Quatermass and the Pit) as Fuchs, and even his motivations seem a bit murky. Apart from Corbeck’s villainy, the characters lack strong definition. Things just seem to happen, before we get a rousing climax and a fairly clever denouement (which beats the finale of Polanski’s The Tenant by five years).

Fuchs (Andrew Keir) battles Queen Tera (Leon)

Yet I keep returning to this film eagerly, and I think it’s for more than Leon (I think). The film does have atmosphere in spades, and there’s something about the muddiness of the storytelling and the way everyone seems compelled to behave in ways that aren’t clearly explained that, curiously, enforce the film’s dreamy qualities. Perhaps there was a stranger, overtly surrealist film just a few script rewrites away. Or perhaps Holt could have pulled all this together into a concise and pulpy little horror tale. Regardless, it exists comfortably on the same continuum as other Hammer films from the early 70’s, experimenting with the familiar formulas in creatively satisfying ways while promising their audiences the usual sights of splashing blood and plunging cleavage. I’ll keep coming back to it; I’m cursed.