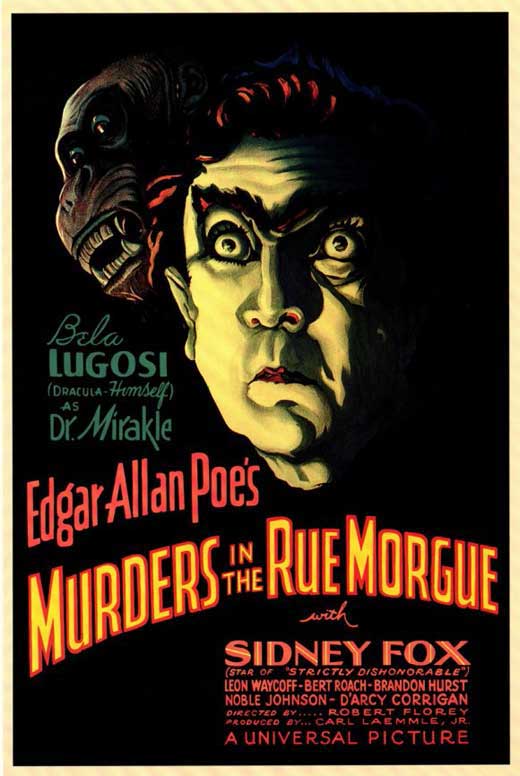

Following the runaway success of Dracula (1931), Universal quickly arranged a follow-up vehicle for its new horror star. Bela Lugosi was reunited with producer Carl Laemmle, Jr. for Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), while the striking Hungarian also farmed out his talents for Fox (Chandu the Magician) and Paramount (Island of Lost Souls). In retrospect, this period would sadly be the height of his film career before a rapid slide into lower billing and poverty row productions. For Rue Morgue he was easily slotted into the role of Dr. Mirakle, whose profession as a carnival showman displaying his gorilla Erik before paying customers disguises his true passion as a mad scientist. It’s a role that would typecast him in future decades as the sort of villain who plots to create invisible rays or atomic supermen, though here his features are uniquely distorted by a unibrow that would require hedge-clippers to maintain. He even has a ghoulish henchman played by the prolific Noble Johnson (The Most Dangerous Game, King Kong, The Mummy). If this does not seem to resemble any of Edgar Allan Poe’s original mystery tale, strap yourself in. Dr. Mirakle’s ultimate pursuit unfolds in a cellar laboratory borrowed from the set of Frankenstein (1931). “My life is consecrated to a great experiment,” proclaims Lugosi to a girl he’s kidnapped and brought to his lair. “I tell you I will prove your kindship with an ape! Erik’s blood shall be mixed with the blood of man!” Specifically he’s interested in the blood of a woman, when attractive Parisian Camille L’Espanaye (Sidney Fox, hot off Laemmle’s film adaptation of Preston Sturges’ play Strictly Dishonorable) catches the gorilla’s eye: Erik steals her hat through the bars of his cage, then sniffs it with fetishism.

Dr. Mirakle (Bela Lugosi) confers with his assistant (Noble Johnson) while the gorilla Erik waits in the carriage.

This early on, we’re clearly flirting with that peculiar pre-Code subgenre obsessed with ape/woman congress, most explicitly treated in 1930 with the overtly racist Ingagi, whose titular African tribe cross-breeds with apes, and whose poster depicts a gorilla fondling an abundantly topless woman. At least King Kong (1933) treats the taboo subject a bit more respectably, never going much further than the king of Skull Island stripping a few items of clothing from the body of the unconscious Ann Darrow. Amazing that Charles Darwin could get our society so hot and bothered. The Scope Trial of 1925 was a recent memory, and Rue Morgue brings its topic front and center. Dr. Mirakle makes it the theme of his carnival act, though the concept remains a sideshow for much of his audience. “Did you hear what he said?” one character asks, to which the other scoffs: “That we might be the production of evolution?” Erik is played by makeup artist Charles Gemora, who would don gorilla suits in numerous films including The Chimp (1932), The Sign of the Cross (1932), Island of Lost Souls (1933), Road to Zanzibar (1941), and Africa Screams (1949); he was also, naturally, in Ingagi. His work here is absurdly compromised by close-ups of a chimpanzee’s head, shot in such a way as to attempt to make it larger than it is – an effect that’s never convincing.

Dr. Mirakle is confronted by Pierre Dupin (Leon Ames).

Certainly there are nods to Poe’s story. The protagonist is named Pierre Dupin, after Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin. But the Dupin of the story was a detective solving a murder (Poe’s was the first detective story). Pierre, played by Leon Ames (billed as Leon Waycoff), is an ill-defined character who has forensic detective skills, but is primarily a bland hero whose purpose is to protect and rescue his girlfriend Camille, the object of the gorilla’s affections and Dr. Mirakle’s scheme. His most impactful moment comes when he bribes a mortician so he can personally perform an autopsy on one of Dr. Mirakle’s victims, found floating in the river. But Ames’ limp performance only underlines the distracting American-ness of this 19th century Paris. The city survives better with its production design, by Charles D. Hall (Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein), and its cinematography, by Karl Freund (fresh from Dracula and soon to direct The Mummy). When the film breaks free from basement laboratories and Parisian parlors, we are treated to fog-smothered streets that come to steep precipices over the dark Seine, and a finale in which Erik scales sharply slanted rooftops with Camille slung over his shoulder. Director Robert Florey, who was awarded this film after being abruptly removed from Frankenstein, is heavily influenced by The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), though he doesn’t push his visuals to such dream-like extremes. There is, however, an abundance of style, and Florey’s attempts to punch up certain moments are appreciated, notably in the climactic moment of horror when Erik is let loose in Camille’s apartment, strangling her mother and stuffing her up a chimney while Florey cuts in quickly to the faces of those residents gathered on the steps listening to the awful noises coming from behind the door. (It’s also a relief to finally get a moment taken from the source material, though the film’s narrative approach completely removes any of the original’s mystery.) And for Pre-Code luridness, there’s little that can top Lugosi gloating over his captive early in the film, her negligeed body bound to an X-shaped cross while he draws blood from her to mix with his gorilla’s. Murders in the Rue Morgue is now available on Blu-ray from Shout Factory, who have been making the most of a licensing agreement by steadily releasing Universal Horrors box sets that look beyond the classic monsters. This is only available as a stand-alone disc, perhaps because it’s been long awaited by Universal horror fans and should sell well enough on its own. The presentation, pristine and eye-popping, has been worth the wait.