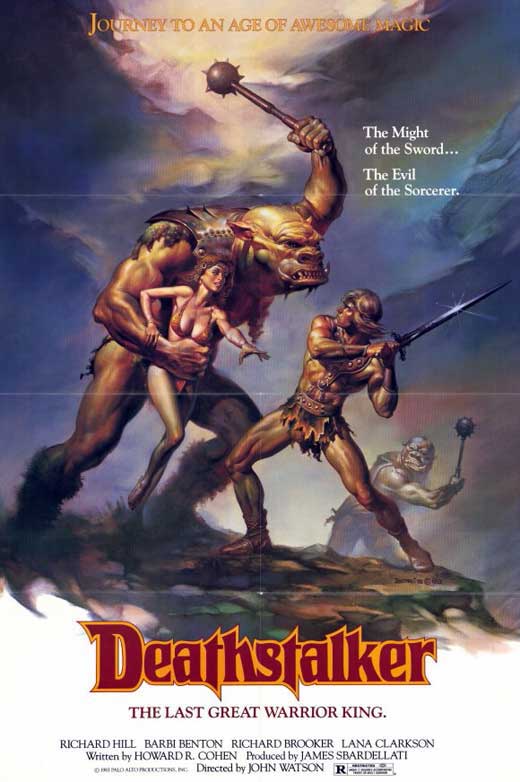

The success of Conan the Barbarian (1982) didn’t just make Arnold Schwarzenegger a star; it also launched a thousand knock-offs. Roger Corman was behind a good number of them, naturally. In the early 80’s Corman was invited by two members of the Argentine film industry, Héctor Olivera and Alejandro Sessa, to make some films in Argentina, in light of the country’s economic woes at the time and the low rates, skilled labor, and subsidies the country could provide. First out of the gate was the Conan clone Deathstalker (1983), co-produced by Olivera and Sessa, with a largely Argentinian crew and directed by James Sbardellati, who had graduated up the Corman ranks after acting as an assistant director on films like Humanoids from the Deep and the Star Wars cash-in Battle Beyond the Stars (both 1980). In the years that followed, the Corman/Olivera/Sessa partnership would produce The Warrior and the Sorceress (1984), Wizards of the Lost Kingdom (1985), Barbarian Queen (1985), Amazons (1986), and Deathstalker II (1987), along with a handful of films with no fantasy element. These constitute only a fraction of the sword and sorcery films released to exploit the success of Conan; they don’t even represent all of Corman’s. Yet the trashy, trashy – let me pause to think of another appropriate adjective – really trashy Deathstalker stands as the most iconic film of this motley crew for two reasons. The first is the glistening-muscle poster art by Peruvian-born painter Boris Vallejo, who was closely associated with pulp fantasy thanks to his airbrushed covers for Conan, Tarzan, and Gor paperbacks, as well as The Savage Sword of Conan magazine from Marvel and the many “Boris” art books which became staples of the fantasy section of every bookstore. The second is the sheer ubiquity of the film in the 80’s – the fact that it was given a theatrical release seems marginal in light of its constant presence in video stores and on late night HBO. Through 1991 the film would spawn three sequels, each attempting to lure more customers with its Boris art and the promise of some lowbrow sex and violence.

Deathstalker (Richard Hill) and Princess Codille (Barbi Benton).

Deathstalker certainly doesn’t stand out from the pack for anything quality-related, artwork aside. Corman’s penny-pinching and disinterest in anything that’s not a commercially exploitable element is evident throughout, which is also, of course, a mark in its favor if you’re viewing it strictly for camp value. Anything not featuring sex or violence has been trimmed, leaving a narrative that’s not boring, but possibly whiplash-inducing. A creature featured early in the film looks like one of Ernie Kovacs’ Nairobi Trio; another is a hand puppet that eats the eyeballs and fingers of a chained slave. Most women are naked most of the time. One of the most amusing things about the film is comparing what’s depicted in Vallejo’s art with the equivalent in the film: the towering pig-faced ogre is a much more pathetic – and human-sized – creature on celluloid, whose biggest moment might be when he picks up a pig’s head from a banquet platter and takes a cannibalistic bite out of it. Our hero introduces himself as an antihero’s antihero by rescuing a “girl from the valley” who’s about to be raped by mutants, then molesting her himself. (Whether or not you count this as a sexual assault depends on how you interpret the sexist trope of the woman immediately enjoying the experience. That makes this scene less hard-edged than I remembered it – though as soon as they’re interrupted, she slips off, hopefully for greener pastures and better roles.) Deathstalker meets a deposed king who asks him to find his daughter Codille, but our protagonist doesn’t take much interest until a witch promises him great power if he takes possession of three magical items, “powers of creation”: a sword of justice, an amulet of life, and a chalice of magic. The latter two are in the possession of the evil Munkar (Bernard Erhard), who wishes to secure his grip on the throne by staging a fighting tournament, the sole purpose of which is to destroy the strongest men who might threaten him. One of those contenders is the athletic swordsman Oghris (Richard Brooker), who can be distinguished from Deathstalker because when he rescues a maiden he doesn’t rape her, and also because he has a British accent. Later, Deathstalker kills him, naturally. I forgot to mention the scene when the witch suddenly appears in a reflection in a river, shrieking at our hero, “Deathstalkah!”

The sinister Munkar (Bernard Erhard).

The first half of the film is a hodgepodge of random fantasy ideas and names, none of which mean anything to the audience, and which, honestly, probably didn’t mean much to screenwriter Howard Cohen (Saturday the 14th), either. 80’s sword and sorcery B-movies, particularly those from New World, are unlikely to offer up any Tolkienesque maps or rich fictional histories. It’s inexplicable when Salmaron (Augusto Larreta), imprisoned in a cave with a rubber puppet for a face, tells Deathstalker that he’s prophesied to be rescued by “a boy who is not a boy,” and just as inexplicable when Deathstalker leads him out of the cave by turning into a boy and then back again. Munkar’s servant Kang (Victor Bo) turns into a hawk at the story’s outset, but it’s a concept which is never brought up again. The three “powers of creation” are just tokens for Deathstalker to collect, like in some 80’s fantasy board game. Honestly, all of this is in the tradition of lesser sword and sorcery dating back to the genre’s initial boom in the late 60’s with Robert E. Howard and Edgar Rice Burroughs imitations, continuing with the numerous loincloth-clad barbarians of comic books in the 70’s; movies were the natural next step. (Even the official Conan sequel, Conan the Destroyer, and the unofficial one, Red Sonja, have more in common with thinly-plotted barbarian pastiches than anything Howard wrote in the 30’s. Those movies aren’t that much more respectable than Corman’s.) But Deathstalker takes license from Conan the Barbarian‘s R-rated edge by deploying sex and gore at a constant, assembly-line pace. Lana Clarkson, later star of Barbarian Queen, wears nothing but a cape and a thong – we see her bared breasts before we see her face. Buxom Playboy model and one-time country music star Barbi Benton, as the captured princess, spends most of the film struggling (and failing) to keep her clothes on while thugs and mutants and a Deathstalker paw at her. Munkar’s palace is like a medieval Playboy Mansion, one with a mud wrestling pit conveniently located in the throne room. Deathstalker is not a good movie, but it knows exactly what kind of film it wants to be: trash, with some wizardry thrown in. It’s a low bar to clear, but low is what Deathstalker is all about.