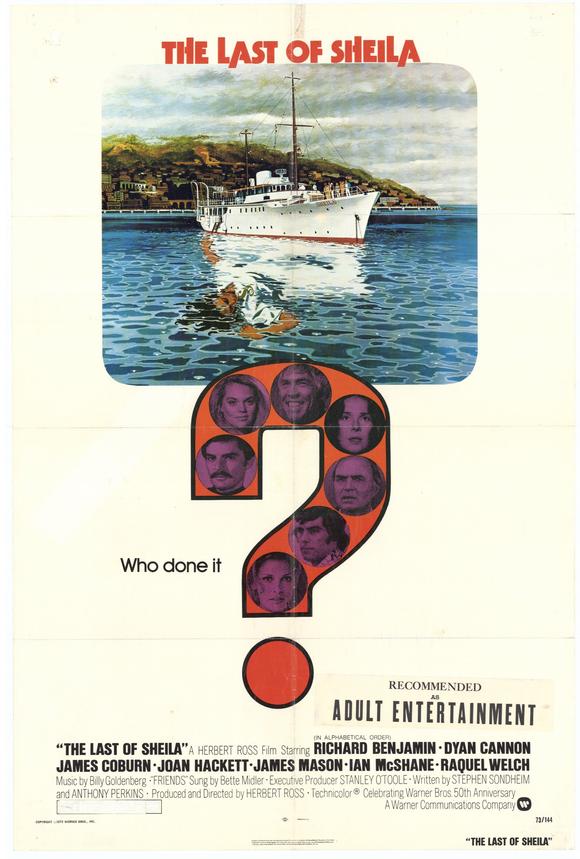

One of the fascinating traits of the murder mystery is that a story can get away with complete misanthropy without leaving a bad taste. All the characters can be bastards, though usually the detective is given a reprieve. The analysis of the crime, the sorting through motives and clues digging down to the rotten core of events, is what matters; it is the process of solving the puzzle, however much it means exploring the private lives of some very unpleasant human beings. Some murder mysteries, most recently in Rian Johnson’s superb Knives Out (2019), let viewers indulge in the pleasures of the genre while threading the backbiting behavior of its characters into its satirical theme. One of the films that influenced Johnson, The Last of Sheila (1973), does the same, but using Hollywood types as the satirical target. The film has a unique genesis, being the only screenplay written by actor Anthony Perkins and musical darling Stephen Sondheim. The two collaborated on murder mystery parties and scavenger hunts with elaborate puzzles for their showbiz friends, much like the game organized in The Last of Sheila by film producer Clinton Green (James Coburn). The film, then, becomes an extended invitation to audiences to participate in a Perkins/Sondheim party, a celluloid game that can truly be solved before the solution is announced. That it works equally as well as a savage exploration of Hollywood is a nice hat trick.

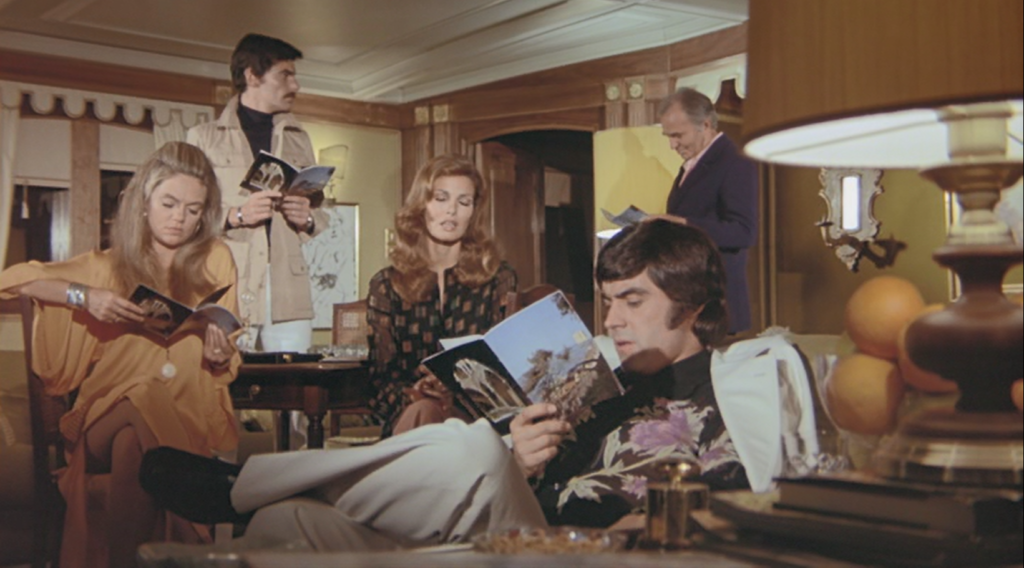

Film producer Clinton Green (James Coburn) and washed-up actress Alice (Raquel Welch) on Clinton’s yacht Sheila.

After a prologue in which we witness the death of gossip columnist Sheila Green, killed in a hit-and-run after leaving a party, we advance forward a year, as her husband Clinton issues invitations for a week in the Mediterranean aboard his yacht, named after his wife (and production designed by Ken Adam). Those invited include talent agent Christine (Dyan Cannon); fading movie star Alice (Raquel Welch) and her husband and manager Anthony (Ian McShane); screenwriter Tom (Richard Benjamin), who’s desperate for work, and his wife Lee (Joan Hackett); and aging director Philip (James Mason), who’s been reduced to directing dog food commercials. Watching this film after the posthumous completion and release of Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind, it’s hard not to see coincidental parallels between Coburn’s performance as a pompous, jaded, and mysterious impresario, barking orders into a megaphone while kicking up foam on a motorboat, and John Huston’s character in the Welles film, keeping heads spinning while lording over his industry guests – both keeping busy by commandeering their social lives into a meta-movie. Sheila director Herbert Ross (whose credits include, among many others, Pennies from Heaven, The Goodbye Girl, and Footloose) for a while keeps up a pace almost as frenetic as Welles’. We learn that all of the invited, save Lee, were present at the party the night Sheila was killed, and Clinton expresses an interest in making a film about her life. He’s devised “The Sheila Green Memorial Gossip Game.” Each of the guests are given a card which they’re to keep secret from the others. This contains a kind of gossip branding, such as “the shoplifter” or “the homosexual.” Every night, “at 8:00PM sharp,” they will disembark and follow a clue based on the identity of the card and, ultimately, try to determine who’s in possession of that card. Once the person who holds that card solves the night’s puzzle, the round comes to an end. Clinton keeps score on a chalkboard in his yacht.

Dyan Cannon as Christine.

The game at first begins as a boozy romp with a bit of casual infidelity added to the mix, but it’s not long before the guests begin to realize that the cards they’re holding may actually be real gossip about each other: Tom tells his wife that Alice was rumored to have shoplifted. Then, while relaxing in the sea, someone is almost killed, in what may or may not be an accident. From there, the game derails in an unexpected way that I won’t reveal here (needless to say, watch the film before venturing onto the Wikipedia page). What I will say is that the performances, with the unfortunate exception of Welch – playing a character based on herself! – are excellent. Cannon’s hilarious and charming talent agent, based on her real-life agent Sue Mengers, is a major stand-out. And throughout the game, Perkins and Sondheim plant clues in the wide open, many of which are rooted in the behavior, histories, and personalities of the characters. The Last of Sheila, which Clinton says will be the name of the movie he makes, is not just a whodunit, but a who-are-they-really. Buried secrets emerge which have a direct bearing on solving the mystery and where the story goes after the mystery is over, right up to the indelible final images and credits (set, sardonically, to Bette Midler singing a ditty called “Friends”). The portrait that emerges is Hollywood as survival of the fittest, enacted here with murder, blackmail, and casual betrayal. One of the subtle recurring jokes is how the suffering of others is shrugged off by our callow cast: “I don’t like getting morbid!” declares McShane’s Anthony when someone attempts to discuss a gruesome death from the night before, while Alice asks, “Is it terrible, just terrible, to wonder if you can get a good hairdresser in this town?” These people have business to get to, new contracts to chase, new infidelities to initiate. In the career they’ve chosen, murder just isn’t that big a deal.